I first met Harry in the summer of 1993, when my research group visited the department of chemistry (MOLS) at the University of Sussex in advance of our relocation there in October. Having tea by the lily pond, I was overwhelmed to be joining an extraordinary group of distinguished faculty. They were all incredibly friendly – and remarkably tanned and fit, due in part to regular (and competitive) lunchtime tennis matches.

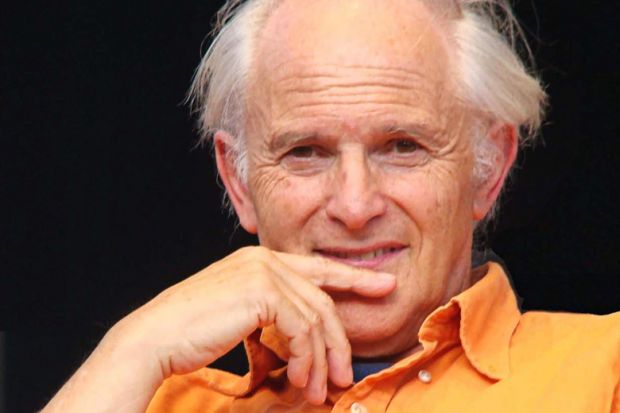

Harry introduced himself – trademark sunglasses and smile – and gently quizzed me about my research programme. We did not have much in common scientifically, but he was supportive of young people and genuinely excited by all aspects of chemistry.

As time went by we got to know each other, mainly because we used to bump into each other in the department (or the car park) at the weekend, but also, from time to time, through chatting about chemistry over tea or in his chaotic office.

He would have often been globetrotting during the week, giving lectures to large audiences on the discovery of buckyballs. But despite his great success as a researcher, Harry was committed to students and to being a part of the life of a university department.

Harry loved giving spectroscopy lectures to the first-year students, and he regularly gave research seminars – this despite the fact that he was “on the road” seemingly continually – enthusing about buckyballs and nanotechnology.

He cut a dash as a speaker, and was incredibly charismatic. He combined excitement, wonder and energy whenever he spoke about science, maths, art, the footballer Rodney Marsh, Richard Feynman, music, Sussex or a recent design he’d worked on. He had one speed in life: fast.

I remember him giving the most extraordinary research lecture on chemistry and interstellar space; not primarily about C60, but rather about fundamental spectroscopic studies. It was great work, with the potential to offer insight into the molecular origins of life. I recall a discussion about the origin of amino acids (celestial molecules or not?) and I did ask him if he somewhat regretted having been diverted by the discovery of C60. He just smiled!

In 1996, Harry (along with Robert Curl and Richard Smalley) received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of fullerenes. It was the only time I ever saw him speechless, and somewhat dazed. The following day we had a reception in the department – all the students and staff – by the pond, with Harry receiving congratulations from one of his heroes, Kappa (Sir John Cornforth).

In the 1990s, nanotechnology was still in its infancy, and the discovery of fullerenes was a watershed moment for nanoscience and perhaps for chemistry as a whole.

Despite his great successes, Harry remained down to earth. Always a great believer in the skill and flair of individuals, he took great interest in people in the department. He also enjoyed parties, and I remember him coming to our house in Lewes for one. It was a glorious sunny day and it was packed with students and staff, and we were drinking Harveys and red wine. Some of us suggested creating a 6ft sculpture of a buckyball (diamond or graphite!) to be entitled Harry’s ball. He was never convinced.

Harry was also passionate about education and public engagement, and he founded the Vega Science Trust, whose archive contains some unique footage of many of the science greats. Vega never seemed to quite take off as I thought it should, but maybe Harry was too far ahead of his time or perhaps trying to do too many things at once.

Harry and I both left Sussex around the same time, he to join Florida State University. We happened to meet at another party in Brighton the day after his formal departure from Sussex after 37 years on the faculty. I think the sunglasses were hiding the tears.

We kept in touch from time to time, mainly by email, and I went over to see him at his Sussex home in his beloved Kingston. We talked for some hours and he played his Martin guitar. That was perhaps the last time I saw him..

Harry was part of a cluster of great chemists in the late 20th century at Sussex. Sadly, many have since died, including Colin Eaborn, Michael Lappert, John Murrell and Sir John Cornforth. These modern-day explorers of the periodic table had a huge impact on organic and inorganic synthesis, polymer and materials science and chemical biology. They were rigorous, curious researchers, but each with a spirit of humanity, collegiality, warmth, good humour and humility – the epitome of a great faculty.

Harry was a star that shone brightly, even among those stars. He was a creative academic researcher, an exceptional teacher, a committed scholar and a charismatic communicator.

Harry, it was a pleasure to know you. You taught us a lot.

Stephen Caddick is director of innovation at the Wellcome Trust and professor of organic chemistry and chemical biology at University College London. This post originally appeared on his blog.

Write for us

If you are interested in blogging for us, please email chris.parr@tesglobal.com

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?