“Chastity does not seem to be considered a virtue among [Tahitian women], for they not only readily and openly trafficked with our people for personal favours, but were brought down by their fathers and brothers for that purpose” – Journal of Captain Samuel Wallis (1773)

This book, aimed at the general reader, offers a panoramic study of sexual behaviour and attempts to control it across five centuries of globalising empires. This is not just “sex in the city”. It’s sex in the Americas, India, Africa, the Middle East, the Pacific Islands, China and Japan. So hang on to your hats or, as in Julie Peakman’s world, your dildos, for here come polygamous sultans, Chinese peep shows, debauched English clerics, horny sailors, gay samurai, animal shaggers, even hornier Mughals, spurned cannibals, lesbian harems, enslaved eunuchs and near-universal pederasty…

Spanning the period from the 1400s to 1900s, there’s plenty to titillate and shock. With more than 100 beautifully produced photos (most full colour and some full frontal), there’s something for everyone. No doubt every gentleman’s club will have their library copies well thumbed. It’s highly amusing in places too. Look out for the almost unbelievably appropriate names for a few of the characters. Richard Cocks headed the British East India Company in the Japanese port of Hirado in 1613. “I bought a wench yesterday,” he boasted in a letter home, “cost me three Taels for which she must serve five years, and then repay her purchase money.” So began a prolific use of local women for sex. And let’s not forget General William Rufus Shafter…

But this book amounts to more than Carry on up the Empire meets Fifty Shades of Grey. It has a serious message: at the heart of all empire-building is a form of sex culture that varies according to time, place and people’s experience of it. Moreover, Peakman’s diligence and previous work on sexual pleasure, perversity and whoring lead her to conclude that “a new type of licentiousness occurred around the mid-sixteenth century born of travel, integration and mixing with people from other parts of the world, creating a blend of ideas and practices that formed the making of modern sexuality”. She identifies four shared features shaping new sexual cultures across empires: the influence of religion; relationships, including same-sex ones; the effects of the clash of cultures and the impact of new hybrid variants; and definitions of what was considered “normal” and “deviant” sexual behaviour at any one time.

Peakman consulted hundreds of primary sources, including legal reports and erotica, and visited archives all over the world. Her encyclopedia of imperial sex has a formula that is repetitive but effective. Each chapter begins with a short history of a particular empire caught with its trousers down. This is followed by the ups and downs of established precolonial sex practices and how these changed over time. Then we have the views of early arrivals, usually European travellers, missionaries, empire builders or wannabes, that climaxes in some kind of surge in sexual activity before the real cavalry arrive – the wives and single women. Impressively, Peakman manages to abstain from using the overused phrase, “imperial penetration”.

For specialists in the history of empires, who have worked on specific locations in relation to sex, gender and sexuality for many years, this book gives surface coverage to some well-trodden ground, focusing on the usual suspects. But it is new for an expert on the history of sex to write with such comparative sweep and include non-European empires among her eight case studies, so this should open up the topic for a general audience and those studying the history of empire but not naturally drawn to gender history.

I first started including gender and empire in my teaching in the late 1990s, having attended lectures by Ronald Hyam and Rosalind O’Hanlon at the University of Cambridge. My offerings on “Sex, Men and Imperial Expansion’’ and “Sex, Women and Imperial Control” were inspired by their path-breaking work. The problem was that students generally weren’t that keen. For them, academics talking about gender relations was like their parents having sex: they knew it went on but preferred not to be in the vicinity when it did. This book will certainly provoke classroom debate. Peakman does not encumber herself with extensive engagement with the complex historiography on empire and sex (for example, there is no critical discussion of Hyam’s research, including his imperialism and penis envy thesis, set out in books such as Understanding the British Empire (2009)). Nor is she bound by political correctness. She writes from a strongly Western feminist perspective. She uses the term “pederasty” and never “paedophilia”. (I found the chapter on Africa rather clichéd, and in a few places inaccurate.)

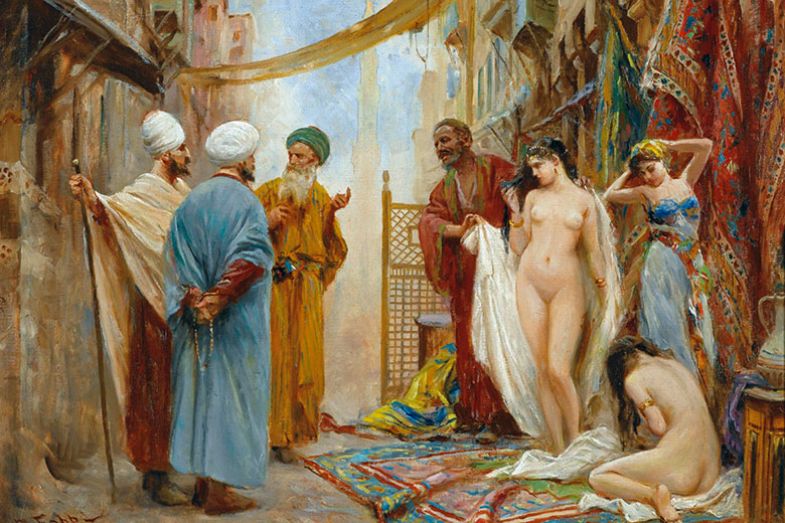

Nevertheless, it is useful for imperial historians to read what an expert on the history of Western sex makes of it all. Because of all her heavy lifting, Peakman brings some important material to the chaise longue. She foregrounds the extraordinary (and few) women who survived abuse, captivity and exploitation to play a major role in spreading imperial influence through relationships based on sex. For example, Roxelana, a sex slave in Suleiman the Magnificent’s harem, rose to power after he fell in love with her. Ottoman rulers preferred to marry slave girls rather than take brides from elite families, so as not to dilute their prestige. Roxelana inspired her man to establish laws to protect the most vulnerable from sexual predators. But she took no chances, contriving to have the son of a rival concubine executed.

Peakman also turns her attention to sex and violence both in conquest and in the everyday. The sex lives of both the wives and the slaves of plantation owners were often grim. William Byrd in late 19th-century Virginia confessed to not liking women in his diary. Sexually impotent, he recorded routinely forcing women to feel his “roger”, grabbing them by the breast or “cunt”, before following through if he could. The rape of women in imperial wars and the mutilation of their bodies is a book in itself.

Finally, Peakman does not flinch from describing the cruel treatment of women in pre-imperial sex cultures and non-European empires. Elite women were shut up, controlled, subservient, deliberately starved of affection. Meanwhile, the poorest village or town prostitutes were vulnerable to infections and, “as their looks faded, their income dried up and many ended up begging, starving or committing suicide”.

A book on imperial licentiousness can no longer function today as the thinking man’s Viagra. There’s too much violence, misery, misogyny, venereal disease, cruelty and death, meted out to women, girls, young boys, homosexuals and cross-dressers. Empires create opportunities to indulge in extreme forms of power, including access to sex in all its forms and excesses. This might well have functioned as an added temptation and the ultimate aphrodisiac. But reading more than 300 pages about what that usually meant for its victims is a real turn-off.

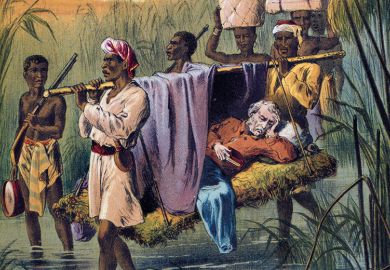

Joanna Lewis is associate professor of international history at the London School of Economics and the author of Empire of Sentiment: The Death of Livingstone and the Myth of Victorian Imperialism (2018).

Licentious Worlds: Sex and Exploitation in Global Empires

By Julie Peakman

Reaktion, 368pp, £25.00

ISBN 9781789141405

Published 30 October 2019

The author

Julie Peakman is an honorary research fellow at Birkbeck, University of London.

Where were you born and where did you spend your early years?

My family moved to Wigan when I was about 7 and that is where I spent my formative years – in a 19th-century broken-down pit town. When we arrived we were in lodgings – just how George Orwell must have first glimpsed the place. I remember my mother wandering into the back garden while she was pegging out the washing and asking about all the black stuff coming down from the sky. The soot got everywhere.

After about six months, my mum found us a cottage in the countryside on a farm. I had a pretty independent life madly running round with the dogs, foxes and rabbits in fields. I remember one incident when country tally-ho yobs on horses with bloodhounds came into our field chasing a fox, which ran into our house for protection. I must have been about 8 years old standing behind the door with a fox, both our hearts beating as if our chests would burst, my mother outside with a broom shouting at 20-odd foxhunters to get off our property.

I remember several early schoolteachers who encouraged me. Mr Britten at junior school allowed me to write and craft my own books (I still have them) – I was about 8. Miss Beards, my first- and second-year English teacher in senior high, gave me top marks in history and told me I was good at the subject. My piano teacher Dorothy Mitchell was also a wonderful mentor, suggesting I should do music at university as I always had distinctions in my exams, thanks to her. But then boys and pubs got in the way. You could go to the Wigan Casino and dance the night away to soul music. People used to come from London and all over just to dance.

My mum was a great influence on me, although I didn’t realise it at the time just how much. At 15, I applied and got into the Corona Drama School and applied for a grant (even though they were not mandatory for anyone my age or for that purpose). I got the grant and went to London, sharing a flat with three older girls in Parsons Green. My mum said she saw how determined I was and supported me all the way. I managed to get a job at a theatre in Drury Lane, working as a dresser to the male spear-carriers – they collected money every week to give me tips.

Where did you go to university and how has that shaped your subsequent intellectual development?

I hadn’t really planned university. I had left school with only four O levels as I had not gone there for the last year since I hated it so much. It was an all-girls school and most of the teachers wanted to knock any spirit out of the girls and mould them into teachers. I was bright but bored sick. I wanted to learn ancient Greek, but they only allowed the sixth-formers to learn it, and only those they thought were “Oxbridge material”. I was considered too rebellious (and too young) to buckle down.

I just knew I didn’t want an ordinary job. At the age of 16, after a year in London, I came back to Wigan, decided to go to the local housewives part-time A level course at Wigan Technical College and loved it. There were no demands, only learning. It was up to you to do what you wanted to do. I fitted in well. I worked in lots of temporary and part-time jobs: demonstrating Bontempi organs in Woolworths at Christmas, modelling make-up for Max Factor, one-liners in Coronation Street as a factory girl. I even took a summer job working in the local cotton mill to save up to go to Greece. And that trip part changed my life as I fell in love with Leros (I now have a house there).

While I was out there in 1976, I had the offer of a house to stay in for the year and was really tempted. Then I heard I had got into the University of Manchester, so it was sort of decided for me. I took English and history, looking from the perspective of women’s history. Back then I only had Sheila Rowbotham’s Hidden from History: 300 Years of Oppression and the Fight Against It (1973) to guide me and, of course, none of the (all male) lecturers had much of an idea on women’s history. I wrote a dissertation on “The Victorian Women Workers in the Cotton Mill”. I guess my own stint in the cotton mill had made me interested in the topic.

I returned to London some years later to do an MA at Chelsea College, where I did philosophy with a dissertation about Albert Camus’ theory of suicide (I think I was a bit depressed at that stage of my life). But it was only with another MA in women’s history at Royal Holloway, University of London that I really found my niche. I was advised by the wonderful Professor Penelope Corfield to send my MA thesis on 18th-century women and flagellation to Professor Roy Porter at the Wellcome Institute. He took me on for a PhD on “Cultural, Scientific and Religious Influences in Eighteenth-Century Erotica, 1680-1839”. I was his last student before his untimely death. He was such a great mentor and so generous with his suggestions and ideas. As he said then, my topic was “largely uncharted territory” and I was the first woman to step into it. Since them, my writing (and indeed my career) has been heavily influenced and supported by Professor Thomas Laqueur and Professor Joanna Bourke.

But at the bottom of it all, I think it was my mum and dad who shaped my intellectual development, letting me make my own decisions, form my own moral compass. They were always very thoughtful and kind people, my dad stopping to help someone with his broken-down car when we were all trying to get to the pub; my mother trying to find a placement for a homeless person when we were out shopping, that sort of thing. Now we seem to be in a world where kindness is derided as the behaviour of fools.

How have your earlier books led you to the topic (and the broad sweep) of this new one?

The history of sexuality has always been a prevalent interest for me, mainly because I recognised early on that gender shapes the world. My first book, Mighty Lewd Bodies: The Development of Pornography in Eighteenth-Century England (2003), came out of my PhD. Surprisingly, erotica and pornography in the 18th century were remarkable for their conservatism. They were not simply about fantasies but closely reflected the ideas of the real world, not just about women but about things as eclectic as botany, animalism, electricity and medicine. The 18th-century understanding of the workings of the body and the female mind are echoed in erotica.

After that, I wanted to write Lascivious Bodies: A Sexual History of the Eighteenth Century (2005), exploring ideas about heterosexuality, lesbianism and homosexuality. By the time I had written and edited eight volumes of Whore Biographies 1725-1800 and six volumes of A Cultural History of Sexuality, I was ready to take on The Pleasures All Mine: A History of Perverse Sex (2013). Taking a great sweep time-wise, I explored all kinds of sexual behaviours from ancient Greece and Rome through the medieval, Renaissance and Victorian periods and up to today.

I like to take on a challenge. I look for large projects no one else has yet tackled. Approaching my present book, Licentious Worlds, I realised that no one had undertaken a grand exploration of sexual exploitation globally over 500 years. Empire-building has always been surrounded with the myth of the great white male explorer and his ripping yarns. Often women are not in the picture at all. I wanted to look at women and marginalised men, those who were persecuted or subjugated, and found a very different story. Mostly it was pretty unsettling accounts of sexual coercion, forced marriages, rape and mass murder. But some strong women came through, such as Queen Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba, who declared herself a man, dressed her female handmaids as warriors and waded into battle; and Nur Jahan, wife of Jahangir, who ruled in the stead of her drug-addicted husband.

How would you hope that greater knowledge of sexual behaviour in the past could influence our attitudes and actions today?

Sexual behaviour is fundamental to women’s lives. The Pill has been the greatest gift science has given women, allowing them the opportunity to avoid pregnancy and to work to gain financial independence.

Education is key in fighting inequalities. According to the UN’s latest figures, 131 million girls worldwide are not in school and that number is increasing. Surveys show an estimate of over 90 per cent of rapes going unreported. Women are at risk when they report rape in many countries. According to the International Centre for Research on Women, 1 in 9 girls are married before the age of 15. There is also a direct correlation between lack of education and child marriage.

We need a revolution in thinking. The situation for women has to change for the better. We should learn from history, but it seems we do not. Having charted 500 years of sexual exploitation of women and marginalised men, I hope at least to put the records a bit straighter than men’s glorification of empire.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Empire with its trousers down

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?