A ‘motivation and engagement wheel’ to keep students on board

No university or college educator would dispute the important role of motivation in their students’ academic development. Motivation is alive and well – or unwell – in every student and every class, from undergraduate to doctoral level. Motivation is also generally easy to recognise; it’s pretty obvious when a student is motivated and when a student is not.

But from here, things get murky. Is motivation one thing, or many things? Is it all good or does motivation have negative aspects? How do we assess students’ motivation? How do we sustain motivated students? How do we support unmotivated students?

The motivation and engagement wheel

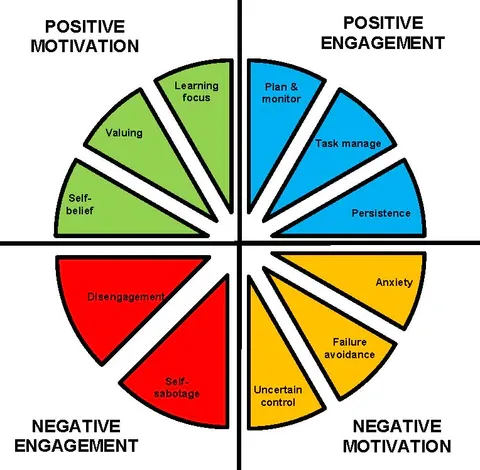

More than 20 years ago, I developed the “motivation and engagement wheel” (below) as a way to represent the major parts of seminal motivation theories in educational psychology. The aim was to develop a model that could be easily communicated by educators to students, be readily understandable by students, help educators and students separate the helpful from the unhelpful, and be a basis for measuring students’ motivation as well as a source for targeted and concrete help for students.

The wheel has four overarching themes, each comprising specific motivation (and engagement) factors. I have sometimes referred to these as the “good” (positive motivation and engagement), the “bad” (negative motivation) and the “ugly” (negative engagement) of motivation. This is because the positive motivation and engagement factors generally yield benefits for students’ academic development (for example, learning and achievement), the negative motivation factors tend to impede students’ academic development and the negative engagement factors tend to have markedly adverse effects on students’ academic development.

How do we boost good motivation (and reduce the bad and the ugly)?

Students’ motivation can be improved and sustained. A few steps are involved. The first is knowing that motivation is multidimensional and knowing its key components – the wheel is helpful for this.

The second step is knowing where a student sits on each part of the wheel. This can be ascertained informally through getting to know the student a little better and observing how they go about their studies. It could involve having a conversation with the student about where they think they sit on the wheel, or a discussion with other educators who know the student. It could even involve formal assessment of the student using a survey tool such as the motivation and engagement scale that I developed and validated to assess students on each part of the wheel.

The third step is to decide what specific components of the wheel will be the focus of educational support. This will in large part depend on the previous (second) step and initially will focus on just one or two components of the wheel, as it is important that educational support is focused and achievable. If several parts of the wheel need attention, educators may choose to focus on low-hanging fruit (where quick success can be achieved), a part of the wheel that the student is interested in or a part that is a significant and immediate barrier to the student’s academic functioning.

The fourth step is to implement strategies that are proven to effectively address the specific component of the wheel. To give a sense of sample strategies, I will select one “good”, one “bad” and one “ugly” part. In guiding my selection, I will focus on parts of the wheel that I believe should be on educators’ watchlist in the age of Covid: valuing (good), uncertain control (bad) and disengagement (ugly).

- Resource collection: Enhance student engagement

- What is student engagement?

- Spotlight guide: Catching students before they fall

A motivation watchlist in the age of Covid-19

“Valuing” is how much students believe that what they learn at university is useful, relevant, important and interesting. In numerous ways, Covid-19 has put students’ valuing of university under pressure. For example, students may question the usefulness of engaging with and learning at university if there is a chance that assessment tasks may be cancelled, classes are called off or they start worrying about the jobs they are studying for (such as jobs in the arts or tourism that are under threat, or jobs in front-line health where essential workers are under huge stress).

“Uncertain control” is when students do not feel a great deal of agency or influence in their university studies, they develop a view that their efforts will not lead to desired outcomes or they feel a sense of helplessness in their academic life. Covid has presented students with all sorts of external pressures that are beyond their control. There has been a lot of external “stuff” piling up on students such as lockdown, isolation, illness, rapid shifts in and out of remote learning, and insecure work. This can reduce their sense of personal control and agency.

Disengagement is when students give up and detach from university, reduce their efforts and withdraw their participation. There are typically many factors that play into disengagement, but as relevant to this discussion, low valuing and uncertain control are two potential culprits. When a student sees no relevance and usefulness in university and when they genuinely believe they have little or no control over their academic life, is it any wonder they are at risk of disengagement?

Bringing these ideas together, a couple of practical strategies are indicated.

One is to bring greater certainty and control into students’ academic lives, so they can be confident that their efforts are worth it. For example, amid the uncertainty of Covid, educators might emphasise three parts of students’ lives that they do control: effort (how hard they try), strategy (the way they try, such as how they present their work, study strategies they use and so on) and attitude (what they think about themselves, their instructor).

Another is to develop alternative ways students can value university. For example, if the usefulness of a subject is difficult to demonstrate, educators can harness what is referred to as “intrinsic” value such as setting a fun activity, arousing students’ curiosity, injecting humour into the lesson and bringing some variety into content, assessment and teaching methods.

Andrew J. Martin is Scientia professor and professor of educational psychology in the School of Education at UNSW Sydney, Australia.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.