WhatsApp and campus trails: supporting students in building peer-support networks

Establishing positive peer relationships is vital for students’ self-confidence and well-being and for developing resilience. The benefits of student peer support groups include building effective communication skills, increasing motivation and confidence in their abilities through knowledge exchange and problem-solving.

Opportunities to socialise have changed for everyone in the past two years, resulting in changes in student behaviour. With this in mind, we have embedded a variety of new practices, into our teaching to facilitate student socialising both in person and using digital tools.

- From struggle to strength: positive psychological growth through teaching and assessment

- How educators can help manage Covid anxieties on campus

- Play on: how to build community on campus through music

How the pandemic has broken down students’ natural social bonds

At university, most students live independently for the first time. Many take on part-time work, experience new cultures in a new city and meet people from different social and cultural backgrounds. They may study abroad, engage in overseas field courses or join sports clubs and societies that widen their view of the world.

So when these opportunities for developing vital social skills are disrupted, as happened because of lockdowns, for example, the effect on young adults is profound. Last year, the UK’s Office of National Statistics reported that loneliness was highest in areas with high concentrations of young people, aged 16 to 24 years, and the unemployed.

The shift to online or hybrid teaching during the pandemic also removed many social aspects of teaching and learning for students, such as group seminars, pair working in laboratories and tutor groups.

In the second half of the 2021 autumn semester, when asked, our level 3, 4 and 5 students reported knowing very few of their peers. When asked about their support network, not a single level 3 or 4 student reported having formed a peer support group. There seemed to be a level of apprehension, mistrust and anxiety among students that had not been seen before. Left unchecked, the consequence of this would be that students would not reap the benefits of peer support.

But teachers can create opportunities for students to meet and form connections – whether face-to-face on campus or online.

Strategies to support students in building a peer support network

Small group learning tasks

Small group tasks where students work together to achieve a shared objective introduce students to their peers and peer-working. Early in the academic year, assign a discussion task or topic to encourage students to chat to their peers; a specific task or assessment gives an initial discussion topic from which other conversations can follow. Examples of how we have used this approach include:

i) a group assessment task to produce a transcript for a natural history film clip

ii) a seminar held the week after an essay topic is assigned to allow students to discuss their ideas for an essay plan in small groups.

Fun group activities

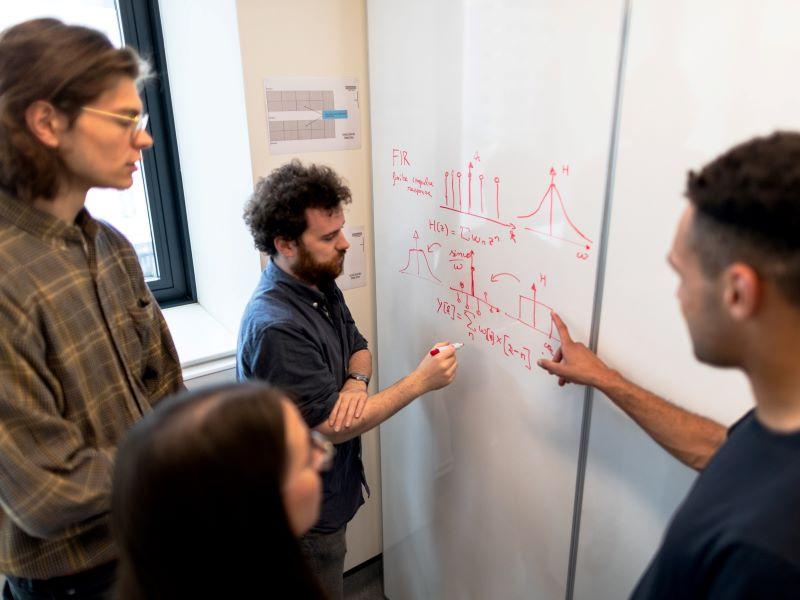

Fun group activities provide students with peer-to-peer interactions in a less formal environment than lectures or seminars. Such activities can combine learning with a social activity. We organised a student-led trail around our campus. Students participated in groups of their course peers (about six students per group), with on-the-spot tasks along the route. Put on the spot to solve a problem, students worked as a team and started to develop relationships among themselves and with staff, whom they had not had the opportunity to meet until this event. Similar events can work in the lab or during welcome week to add opportunities for students to build these important peer-support relationships.

Social media groups

Students can seem well connected online given the widespread media reports of young people being addicted to their smartphones and computers. However, when we asked students about their support network, because students had not formed a peer support group in person, they also had not developed any online connections with peers. We asked them which social media platform they preferred for communication – WhatsApp – and if they would like to be part of a cohort group chat on this platform. The students felt uncomfortable setting this up themselves, with some being anxious about giving their number to people they didn’t know well. In their next lab session, where in-person attendance is highest, we left a sign-up sheet for the WhatsApp group at the front of the lab. Students wrote their phone number without leaving their names to preserve some confidentiality. One student volunteered to create the group chat.

The WhatsApp group made an almost instant difference to the mood in our teaching sessions: the students have in-jokes and have openly talked about the group being useful for both their studies, with timetable information, assessment deadlines and IT issues all shared, and their personal lives through things such as car-sharing and arranging accommodation.

Connect with student societies

When students arrive at university, they are often bombarded with information about the city, the university, their course and the many societies they could join. Understandably, the less “new and exciting” but often more supportive societies can often be overlooked. To remedy this, we offered societies a coffee morning halfway through the first semester. This informal two-hour session offered an opportunity for students to drop in and meet other students who were representing key societies linked to the school of study. The goal was to remind students who might be starting to feel isolated that there are peer-support groups available to them. We made badges for the different societies to ensure that the reps were identifiable and to foster a sense of belonging in the new society members.

A key part of our job is to help prepare students for life after university.

Being part of a supportive community and building meaningful relationships with peers are invaluable parts of a student’s resilience toolkit. These can improve student well-being, both at university and beyond.

Kelly Edmunds is associate professor, and Helen Leggett and Becky Lewis are both lecturers; all are at the University of East Anglia.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

Additional Links

For more advice and insight on this topic, read our spotlight guide on how to build belonging at your institution.