The defence of capitalism as an inherently better system of economic distribution than its alternatives tends to rely on the assumption that it benefits most people most of the time. It’s never a moral argument. Justification of the free market is not bogged down in political, religious or philosophical ideology. It relies instead upon common-sense observations: however much we envy a handful of excessively successful individuals, we still recognise that in general we are all better off.

Caitlin Rosenthal’s history of the accounting and management of slave plantations in the Americas goes a long way towards puncturing common-sense narratives of free market economics. She examines an abundance of precise details held in the records of slave owners. These include the ledgers and records of daily transactions, summary sheets and annual accounts – and the meticulous recording of individual productivity levels.

Double-entry bookkeeping, the perfect record of business through its careful balancing of credits and debits, seems an unlikely place to make a call for social justice. It is, however, the very place where the balancing of slave lives takes place most vividly.

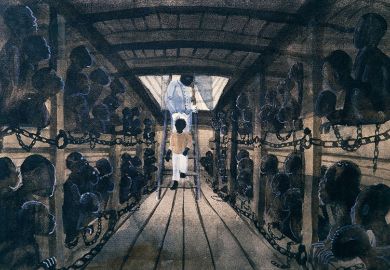

Beyond the profit and loss accounts of revenue, there are the records of capital accruals and depreciations. These contain detailed livestock records, including the black bodies owned at the beginning of the year supplemented by births, depleted by deaths and added to with new purchases.

Diligent slaveholders embraced regular, detailed notation of the skills and attributes of individual bodies. They measured potential output and assigned capital values based on age, skills, productivity and docility. On the eve of the civil war, the capital value of slaves, neatly recorded in thousands of business records, was in excess of $3 billion. The significance of this black human capital value cannot be overestimated: it provided the backbone for the loans and mortgages of southern business and white livelihoods.

What emerges from Rosenthal’s book is a picture of scientific management: entrepreneurialism based on extracting the most value from human capital. She highlights the similarities between these strategies and those deployed to control increasingly large factories and industries employing free white workers. While the meticulous record-keeping is similar, the challenges of managing free labour and controlling enslaved capital are vastly different.

The argument that quantitative information systems were key technologies in controlling the lives of slaves is convincingly made. Although repeatedly underscoring such material with evidence that “management expertise blended well with violence”, Rosenthal notes that she does not engage with “abstractions like hegemony and ideology to explain planters’ control”. In essence, this is an argument from business studies, not politics or sociology. Rosenthal is condemnatory of all aspects of slavery, but a necessary discussion of race, ethnicity and white power often feels as though it is missing.

Rosenthal argues that, from “the perspective of slaveholders and other free whites, the freedom to enslave was an economic freedom”. In which case, the abolition of slavery becomes an act of decommodification and “a triumph of market regulation”. That’s a strong argument and one that should be kept in mind when we make the case for political controls on other activities promoted as desirable proponents of the free market.

Martin Myers is a lecturer in education at the University of Portsmouth.

Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management

By Caitlin Rosenthal

Harvard University Press

312pp, £27.95

ISBN 9780674972094

Published 31 August 2018

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The economics of slavery

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?