No matter the degree of detail, any official map of Los Angeles would miss more than it managed to record. Its lines and grids wouldn’t capture the chaotic, transitory upbringing of a kid such as Stefano Bloch, for example: his stepfather in and out of prison, his mum addled by addiction, his family always on the run, not so much occupying broken-down Los Angeles neighbourhoods as stumbling from one to the next. That official map would also miss the fact that Bloch, in his single-minded effort to become a high-profile, “all city” graffiti writer – a writer whose graffiti were recognisable throughout LA’s many neighbourhoods – had made his own map of the city.

Page after page of this tensely engaging memoir documents Bloch’s elaborate, daily remapping of streets, blocks and neighbourhoods along shifting coordinates of physical access, subcultural status, public visibility and the daily dangers offered up by street gangs and the police. Because of this, as Bloch recalls, his memories of writing graffiti are memories of “experiencing an alternative city” that he and his companions were themselves creating. An essential part of this process was the endless mapping of “spots” – desirable locations for writing graffiti, as defined by their high visibility, potential audience and subcultural meaning. In the pervasive car culture of Los Angeles, as Bloch soon realised, such spots clustered around the freeways. Since viewers were locked inside speeding automobiles, this required Bloch and other writers to use big letters and bold murals in order to be noticed. Here the danger was not only being seen and apprehended while writing, but sprinting across busy freeways in the first place – as when, early in the book, a collision leaves Bloch bloodied and broken. Bloch’s was a street cartography of consequences.

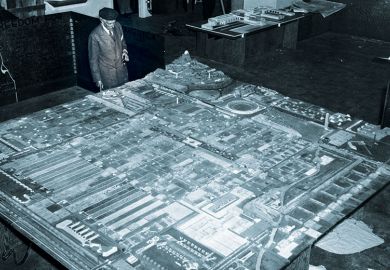

Running LA’s freeways and alleys, jumping its fences, scaling its abandoned buildings, Bloch sometimes traversed a different sort of LA space: its many college campuses. Never much interested in school, and seeing the campuses only as shortcuts, Bloch nevertheless found himself drawn to their grassy calm, in part as escape from the dangerous chaos of his own young life. Enrolling first at an LA community college, he next landed at a top California university, where he won a major award for a project in which he drafted a “cognitive map of the city from the perspective of a graffiti writer”. He went on to study urban planning under Edward Soja at UCLA, to earn a PhD in geography at the University of Minnesota and to land a tenure-track position. But lest this seems a story of a street kid who abandons his past in order to succeed, allow me to argue the opposite. Bloch succeeded because he brought his past with him. In fact, his trajectory confirms what the growing number of ex-graffiti writers sporting PhDs and scholarly publications suggests: the skill, planning and dedication necessary for becoming a successful graffiti writer – necessary, that is, for going all city – can constitute hard-earned preparation for professional achievement. Street cartography, it turns out, can lead to all sorts of consequences. “I still see the city as a writer does,” Bloch notes in an epilogue. Luckily for him and his readers, he does indeed.

Jeff Ferrell is professor of sociology at Texas Christian University and the author of Crimes of Style: Urban Graffiti and the Politics of Criminality (1993).

Going All City: Struggle and Survival in LA’s Graffiti Subculture

By Stefano Bloch

University of Chicago Press

240pp, £53.00 and £15.00

ISBN 9780226493442 and 9780226493589

Published 5 November 2019

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?