Generations of children grew up reading the heroic tales of David Livingstone, Scottish missionary, anti-slavery crusader, explorer, imperialist and martyr. His search for the “source of the Nile” (he believed that finding its origin would give him the influence to end the Arab-Swahili slave trade) has been seen as one of the most inspirational tales of courage, as well as foolhardiness, in the Victorian period.

As a very young child growing up in Zambia in the late 1960s, I remember investing my limited pocket money in an extremely old, tattered book titled The Child’s Livingstone. Initially, I was riveted by the adventure stories based in “darkest Africa”. Then, I came across a description of Livingstone arriving in an African village that was being terrorised by “big lions”. The author, Mary Entwistle, claimed, “At night the lions roared so loudly that the black babies woke up and cried.” When the lions roared at the “black men” who had been armed to kill them, “how quickly they ran home!” Livingstone came to the rescue and, despite being bitten, managed to kill a “fierce, growling lion”. Even as a child, I understood the underlying, racist message: African men were incapable of defending their “black babies”, while white men possessed a vastly superior quota of courage. I was ashamed and never looked at the book again.

Joanna Lewis does not mention Entwistle’s propaganda addressed to children, but her new book on the “myth of imperialism” is an enthralling analysis of the cult of Livingstone and what it tells us about Victorian imperialism, manly heroism and, above all, modern memory. Her main contention is that we cannot understand the British Empire without recognising that it was a “maelstrom of radical feeling”. Only by studying the emotional lives of the protagonists can we explain the psychological attractions of imperialism, the everyday lived experience of the millions of men and women who dedicated themselves to its creation and maintenance, and why it continues to resonate in important ways in cultural memory today.

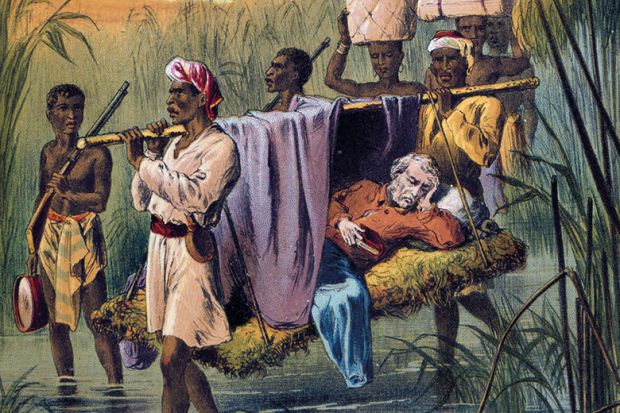

Lewis’ Livingstone (pictured inset) is a complex, contradictory character: ambitious yet generous, cowardly yet capable of acts of extraordinary daring, an anti-slavery activist who treated central Africa as his private playground. But she is not really interested in his actual life and accomplishments, trusting her readers to be familiar with the broad outlines already. Rather, she is fascinated by how his death came to be mythologised into a “tale of manly, masochistic endurance, a biblical parable of redemption”, which ends with “a Christ-like act of self-sacrifice on behalf of all mankind”.

Perhaps the most mythologised aspect of Livingstone’s life was, in fact, his death on 1 May 1873 in Chief Chitambo’s village at Ilala (present-day Zambia). Seven years later, biographer William Blaikie recounted how Livingstone had died on his knees, praying to “the Redeemer of the lost” for “his own dear Africa – with all her woes and sins and wrongs”. Blaikie lied. In reality, Livingstone died in excruciating pain while delirious from malaria. He had suffered internal bleeding due to dysentery. He was not praying on his knees: he was probably crawling to get help.

After his death, Livingstone’s heart and internal organs were removed and buried under a sacred mpundu tree. The rest of his body was embalmed and transported 1,600km to the coastal town of Bagamoyo, where it was put on board the Malwa. After arriving at Southampton docks, it was transported to London and buried in Westminster Abbey. Jacob Wainwright, a freed Yao slave and loyal friend to Livingstone, accompanied the coffin to England, only to be treated with disdain, called a “boy”, ridiculed for his lowly class status and forced to change out of his “pea-green jacket” with a “pair of fieldglasses slung over his shoulder” into something considered more sombre. By all accounts, Wainwright was deeply “unsettled” by his time in England. Lewis observes that contemporary commentators on Livingstone’s life were really only interested in “Livingstone’s love for his African ‘boys’, their corresponding love of him and the suffering of Africa”. Until fairly recently, Livingstone’s many African collaborators were nothing more than sketchy cardboard cut-outs, foils to the Great White Adventurer.

Undoubtedly, Livingstone’s funeral in Britain was an extraordinary display of Victorian sentimentality. Although the funeral itself was chaotic, thousands of men, women and children turned up to see the cortège. Journalists reported with amazement that mourners began sobbing loudly as soon as they saw the coffin. In the words of the Christian World, there were “a 1000 eyes…wet with tears; a 1000 heads were bowed in reverent sympathy and sorrow”. Rather than denigrating such displays of emotion, reporters viewed tears as authentic expressions of the depth of moral feeling. Readers were reminded that, although Livingstone’s heart had been buried in Africa, the rest of his body had “come home in peace” and was “securely resting beyond the roar of the wild beast”.

Livingstone’s burial ground in Africa was in a remote and dangerous region. It took nearly 20 years before European explorers were able to visit it. Finding Livingstone’s heart became the occasion of many heroic (and often fatal) European expeditions. Such expeditions were a complicated muddle of masculine bravado, nationalist hype and economic greed. Explorers were crucial to attempts to steal land as well as advance British and European power over the rich resources of the continent. In short, the Livingstone “enterprise” was part of the European scramble for central Africa. Like Entwistle’s The Child’s Livingstone, stories about Livingstone and his successors became part of a racist and sensationalist conception of Africa, even when draped in a humanitarian banner.

Importantly, Lewis’ book does not finish with the end of colonial rule. Indeed, one of the most interesting chapters examines the way Livingstone’s legacy was deployed in post-imperial contexts. By the centenary of his death in 1973, Zambia had been independent for nearly a decade. As head of the country’s one-party state, President Kenneth Kaunda sought to mobilise the myth of Livingstone to his political cause. Along with members of Livingstone’s family, representatives of Christian groups (including the Bible Society of Wales and the British and Foreign Bible Society) and about a thousand pilgrims, Kaunda walked to where Livingstone’s heart was buried. His aim was not only to remember “a dead man” but also to pay homage to “the place where a freedom fighter died”, as the Zambian Daily Mail put it. Kaunda was particularly brazen in appealing to Zambian Christians, promising an end to the “neglect of reading the Bible” and ending his speech by calling on all Zambians to “love the Lord thy God with all thy heart”.

The centenary of Livingstone’s death in the UK, on the other hand, was marked by the publications of biographies that seriously undermined his heroic, if not beatified, reputation. These books portrayed him as a domineering, deluded, cantankerous and untrustworthy man who mistreated his wife and four children. Oliver Ransford’s psychohistory, David Livingstone: The Dark Interior, even claimed that Livingstone was prone to delusions and probably insane. The contrast between these different interpretations could not be starker. By focusing attention on the emotional lives of empire, Joanna Lewis helps to explain why.

Joanna Bourke is professor of history at Birkbeck, University of London and the author, most recently, of The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers.

Empire of Sentiment: The Death of Livingstone and the Myth of Victorian Imperialism

By Joanna Lewis

Cambridge University Press

304pp, £30.00

ISBN 9781107198517

Published 28 February 2018

The author

Joanna Lewis, associate professor of international history at the London School of Economics, grew up in a village in South Wales but recalls “a second, spiritual home” in mid-Wales where she “spent a lot of [her] early years listening to music, reading Victorian novels and standing in light drizzle waiting for the school bus”.

She decided to study social and political science with history and philosophy at the University of Bath, largely because of a second-year course on English literature and history that got cancelled before she could take it. But it was while doing a master’s and then a PhD at the University of Cambridge that she “learned the rigorous discipline of intensive archival research”. She still recalls the guidance of two distinguished mentors: to “squeeze your argument until the pips squeak” and to remember that “your sources are like small children, they speak quietly so listen carefully”.

As to the origins of her new book, Lewis says that she became “mindful that there was something missing in politically based narrative histories, so I went searching for something I wasn’t sure was there or knew what it looked like”. She had also “never forgotten travelling through Tanzania in 1995, visiting the colonial anti-slavery/Livingstone museums. On the beach at Bagamoyo, where Livingstone’s body left Africa, I remember looking out to sea and thinking how remarkable and compelling was the story of African men and women carrying the corpse to the coast.”

Although “rest assured it does not mention Brexit”, Lewis believes that her book has significant contemporary resonances, since it is “ultimately about the importance to Britain of ideological power at home and in foreign policy…It’s also about the potential of grass-root protest, mobilised through the notion of a shared humanity, to demand an ethical foreign policy…That will only come through emotive activism from below.”

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The emotional resonances of an imperial martyr

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?