Summoned recently to the doctor’s for my annual check-up, I was asked to bring in a urine sample. On arrival, I presented the nurse with a glass jar half full – only for her, immediately, to hand it back. Even though the jar had been cleaned, it could, she told me, be contaminated with the minutest amount of salt or sugar, which would render her analysis useless.

Embarrassed, I put it back in my coat pocket, where it stayed for a week or two until, out at dinner with friends, I wondered what was causing the lump in my coat and produced it, putting it centre table, pondering aloud why I was in possession of half a jar of single malt with a picture of the television personality and spaghetti-sauce magnate, Loyd Grossman, on the label. By the time the penny dropped, it was too late and I squirrelled it away to a chorus of groans. If only I had read Jean-Claude Lebensztejn’s fascinating account of the iconography of “pissing figures”, for he assures his reader that “the association between laughter and urine seems to date from time immemorial”.

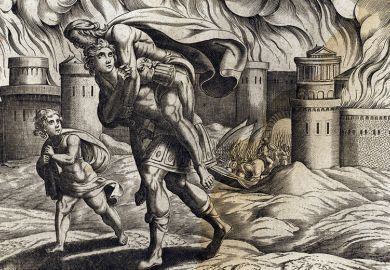

Most striking is the ubiquity of the pissing figure (usually a small boy or putto). This mischievously micturating infant appears in paintings of the High Renaissance, as well as cartoons and satires of the 18th century. Artists discussed here include Titian, Michelangelo, Mantegna, Rubens, Rembrandt, Bosch, Bruegel, Boucher, Hogarth and Cruikshank. From his early appearance engraved on Roman sarcophagi, the pissing child is associated with magic and especially curative powers. Pliny’s Natural History details the therapeutic properties of children’s urine in combating snake bites, burns and ear worms, while old urine is effective on rashes.

Lebensztejn attributes these religious, medical, alchemical and practical powers to a prevailing patriarchy: “with their little instruments they represent virility in action and the power relations inscribed by the phallus in human civilisation”. Consequently, representations of females urinating “are tied, when they appear, to an iconography of exception”. For instance, a ceiling panel from 15th-century Bourges features a girl pissing into a clog: “She opens her gown to make way for a wavy, thick, straight stream, in contrast to the more or less parabolic curves that generally emerge from the penises of little boys; a bit of it drips down her right calf.” Unsurprising, then, that the decline of patriarchy in later times “brought legitimacy to the theme of the pissing woman”.

Just as public toilets were privatising bodily functions, public urination took on a resonance of aggression, provocation or deviance. Duchamp’s infamous Fountain (1917) challenged artistic conservatism as well as prudery concerning physical processes. Picasso’s La Pisseuse (1965) has developed into explicit images such as those by Gilles Berquet, Claude Fauville or Sophy Rickett, while work by Robert Mapplethorpe or Andres Serrano flirts with the profane and the pornographic.

Lebensztejn’s engaging and intelligent study is alert to the ambiguity of piss and “the ambivalent feelings that it arouses: luminous and more or less voluptuous in the intimacy of its discharge, but rather repulsive to smell when it’s not one’s own”. Well, at least my dinner companions ought to be grateful that I remembered what it was before taking the lid off!

Peter J. Smith is reader in Renaissance literature at Nottingham Trent University and the author of Between Two Stools: Scatology and its Representations in English Literature, Chaucer to Swift (paperback, 2015). Most recently, he is the co-editor (with Deborah Cartmell) of Much Ado About Nothing: A Critical Reader in Arden’s Early Modern Drama Guides (forthcoming).

Pissing Figures, 1280-2014

By Jean-Claude Lebensztejn

David Zwirner Books, 192pp, £11.95

ISBN 9781941701546

Published 29 June 2017

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: A steady stream of toilet humour

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?