This book focuses on the idea of pain as instanced in the writings of key Victorian writers. Rather than an in-depth biopolitical study of pain in the era, it looks at how John Stuart Mill, Harriet Martineau, Charlotte Brontë, Charles Darwin and Thomas Hardy regarded pain.

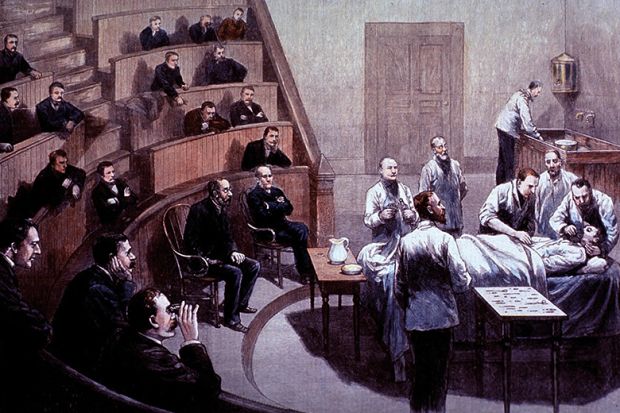

In the introduction, Rachel Ablow does bring in some broader themes concerning pain. She sees a connection between liberal subjectivity and one’s view of pain. Is it individual, social or some amalgam of the two? Should the liberal philosopher be more interested in collective pain or the individual in pain? Are physical and psychological pain the same? Ablow raises the possibility that the 19th century presents a watershed moment in the history of pain because of the advent of effective anaesthesia making pain optional and therefore detached from religious and moral significance.

But the individual chapters largely ignore the grander themes of the introduction. A long chapter on Mill focuses on utilitarian attitudes towards pleasure and pain as the two poles on which all political decisions should be made. A chapter on Martineau focuses on the lifelong invalid as one who has a special detached view of the body politic. Thus Martineau’s objectivity and expertise come from her painful disability. In that sense, she is more aware of the pain of others – the social aspect of pain. Brontë, Hardy and Darwin get similar local attention.

The overall result is less a coherent argument than a series of specific readings of pain as they arise in each of the writers. One can see an attempt to pull together these various viewpoints into something more like a zeitgeist, but the reality of the book is that it seems to be made up of five separate essays in search of an overarching theme. Individually, the essays are talented close readings of specific paragraphs from the five writers, often from a classical philosophical perspective with quirky and unexplained appearances by Spinoza and Wittgenstein every so often.

The book may satisfy Victorianist literature professors, but it will be of less interest and moment to everyone else. The central problem is that it never really breaks new ground on pain. Works by Elaine Scarry, David Morris, Ronald Schleifer and others have done more. Without a specifics of pain, the author is led to think of pain metaphorically or as an adjunct to political theory. Ablow’s tendency is to compare the various authors in a “on the one hand, on the other” fashion, rather than using them as building blocks to a more solid conclusion.

In the end, there is no consensus among the authors, and therefore the book lacks a central position. A telling sign of this lack of argument is that there is no conclusion to the book itself but simply a four-and-a-half page afterword that races from ancient Greece to the 19th century in an attempt to rejoin the larger themes of the introduction. If there is pain in the book, it might be more aptly found in the reader, who is at pains to sort through the parts to find the whole.

Lennard Davis is distinguished professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Victorian Pain

By Rachel Ablow

Princeton University Press

208pp, £32.95

ISBN 9780691174464 and 9781400885176 (e-book)

Published 13 June 2017

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?