The aphorist Emil Cioran wrote, “If anyone owes everything to Bach, it’s God. Without Bach, God would be a third-rate character.” Johann Sebastian Bach’s monumentally affirmative music, from the Passions and cantatas to the instrumental works, does not merely express but justify, and even supersede, faith. Given these lofty achievements, repeated attempts to humanise Bach have succeeded only so far. One path has been through Anna Magdalena Bach, his second wife and mother of 13 of his children.

Johann Sebastian and Anna Magdalena, an accomplished soprano and skilled harpsichordist, compiled two notebooks of music by himself and others, as well as additional annotations. Musicologists have laboured to rationalise these marvels for generations. One popular work to emerge from the notebooks was Bach’s pretty Minuet in G major, until it was established in the 1970s that a composer named Christian Petzold wrote it, although many punters have still not received the memo. Another beloved excerpt from the notebooks, the aria If Thou Be Near (Bist Du Bei Mir), was taken as Bach’s expression of uxorious devotion, until it turned out that he didn’t compose that either; someone named Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel did.

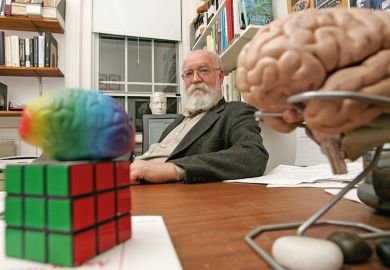

These recurrent misprisions have given licence to some unlikely claims, one of which posited that the celebrated Cello Suites included in the notebooks were not by Johann Sebastian but by Anna Magdalena, a notion roundly dismissed by Yearsley, an organist and professor at Cornell University, and others informed about the matter. Yet even defaming Bach as a plagiaristic male chauvinist would at least humanise him with flaws, instead of leaving him on his lofty perch.

Yearsley has a mustard-keen approach, ready to include extraneous mentions of Beyoncé and Adele, doubtless to entice readers impressed by such. We are informed that Anna Magdalena remains the “most famous wife of a great composer”, whereas Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus (1979) and particularly the film version by Miloš Forman (1984) surely conferred upon Constanze Mozart, another singer, that ranking. This is an informed, punctilious account of the Bachs in their historical context, with fair-minded, even-handed explorations of whether Anna Magdalena might have composed music (none survives) or played the organ (quite possibly). An overstated elaboration of fleeting allusions to fertility in doggerel verse copied into the Notebooks leads to the bluff conclusion: “That Anna Magdalena Bach’s musical Notebook of 1725 indulges in jokes about penis size is a fact as incontrovertible as it has been uncomfortable for guardians of the Bach legacy...”

Bach’s stolid, even stuffy image still cannot compete with the more evidently racy Mozart, although the fact that the former fathered 20 children makes it clear that a bit of the other played a role in his domestic life. Still, as much as we try to make Bach approachable, he remains the formal, somewhat off-putting supreme master as incarnated by the keyboard virtuoso Gustav Leonhardt in The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1968), a film by Jean-Marie Straub that Yearsley slates as cold and uninvolving. Yet efforts to make the Bach household cosy and accessible, as in Esther Meynell’s sentimental fiction, The Little Chronicle of Magdalena Bach (1925), are equally unsatisfying, although they delighted generations of readers, especially in Germany before and during the Second World War. Ultimately, Bach retains his mystery, as superhuman geniuses should.

Benjamin Ivry is university expert in English language and international exchange at Thammasat University in Thailand. He is also the author of biographies of the composers Maurice Ravel and Francis Poulenc.

Sex, Death, and Minuets: Anna Magdalena Bach and Her Musical Notebooks

By David Yearsley

University of Chicago Press

356 pp, £34.00

ISBN 9780226617701

Published 5 August 2019

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: At home with Mr and Mrs Bach

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?