A few years ago, Vladimir Putin deplored the collapse of the Soviet Union as the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century. In this respect, beyond minor criticisms of Stalin and Stalinism, he remains faithful to the vision of the paranoid dictator who passed away on 5 March 1953. Psychologically disturbed, to be sure, Stalin was nonetheless a shrewdly pragmatic Machiavellian who was also fully committed to a number of ideological tenets. He cynically used all means at his disposal to carry out a grand strategic goal: turning as much of the world as possible Red.

He was a dyed-in-the-wool Bolshevik, despite his manipulative espousal of Great Russian chauvinist themes during and after the Second World War. His dream was not a delusion of czarist expansionism but Lenin’s yearning for world revolution. He was an anti-Semite, as Robert Gellately shows, especially during his final years, but his anti-Semitism was, again, political, not racial. Stalin’s cosmology was social, not biological: for him, Jews were cosmopolitans and therefore not to be trusted. Indeed, he trusted no one with Western (or foreign) connections. One of the main victims of the Stalinist purges in Eastern Europe was László Rajk, the Hungarian politician and Spanish Civil War veteran (who incidentally was not, as stated in this book, Jewish).

When the Red Army occupied Eastern Europe during the 1944-45 offensives, Stalin had no intention of allowing for “national roads to socialism”; propaganda devices such as the “National Fronts” were mere smokescreens. For him, as he told the Yugoslav communist Milovan Djilas during the last meeting between Soviet and Yugoslav leaders at the end of 1947, a few months before the eruption of open conflict with Tito, what counted was full Soviet control over the region. This was merely the fulfilment of a project that the vozhd (the “Leader”, in Soviet parlance, and the equivalent of the German term “Führer”) had cherished since the first days of the Second World War. Whoever arrives first, he maintained, establishes political and social institutions attuned to his ideology. Stalin’s curse was to use whatever means were possible to win the Cold War. Not only did he unleash fierce competition with the West, by trampling every single agreement achieved at the Yalta Conference, but he also set the framework under which the global conflict between open societies and their enemies would continue for decades.

This is the main merit of Gellately’s outstanding work: using an enormous amount of information in numerous languages, he highlights Stalin’s geopolitical designs and demonstrates, against revisionist historical claims, that it was the USSR, not the US and her allies, that wanted and provoked the Cold War. This is particularly important now when historical ignorance and poor scholarship meet in attempts to present a dangerously naive US politician such as Henry Wallace, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s vice- president from 1941 to 1945, as a visionary statesman.

A prominent historian of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, Gellately offers a panoramic view of Stalin’s political, diplomatic and psychological manoeuvres that allowed the USSR to achieve superpower status. The author has an encyclopedic knowledge of his subject and provides a compelling narrative of deception, brutality, foolishness and betrayed idealism. The story evolves chronologically, from Stalin’s triumph against his rivals within the Bolshevik elite in the aftermath of Lenin’s death, through the horrors of the Great Terror, the pact with Hitler, the early disasters that followed the Nazi attack in June 1941, and the rise of the anti- Fascist coalition.

Gellately rightly emphasises Stalin’s fixation on internal enemies as well as his dedication to the purity of official doctrine. The chapters dealing with the summits in Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam are truly illuminating, adding important nuances to previous interpretations of those events. Gellately’s view of Soviet international goals differs significantly from the classic formulation issued by George Kennan in the 1940s. Whereas Stalin embraced Great Russian imperial goals, this was not a mere return to the Romanovs’ dreams. Stalin was a Leninist internationalist, and Gellately’s book offers compelling testimony on how this messianic agenda came to be carried out in the aftermath of the war, not only in Europe but also in Asia. The master of the Kremlin knew how to disguise his designs, simulating benevolence and restraint. Yet he approved of and encouraged Kim Il-Sung to attack South Korea and embark on a military adventure with fateful consequences. The difference between Stalin and Trotsky, his arch- rival, lay in their differing views of the pace of communist expansion, not in the legitimacy of such a strategy.

This is indeed a most disturbing point that revisionists must come to terms with: Stalin was intent upon provoking a new world war that he was convinced he and the “progressive camp” could win. Had he not passed away, he might well have set it in motion. In this respect, Mao Zedong, with his metaphor that the winds from the East would prevail over the winds of the West, was faithful to Stalin’s testament. Khrushchev, the champion of “peaceful co-existence”, was in fact the revisionist renegade Mao so furiously denounced.

The instrument Stalin created in 1947 to pursue his ultimate revolutionary project was the Cominform, an abbreviation for the Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers’ Parties. Stalin himself baptised its official weekly publication, For a Lasting Peace, For People’s Democracy. Each word was a lie: he did not want lasting peace and was definitely not a democrat. The journal was first headquartered in Belgrade (moving to Bucharest after the break with Tito). The avatars of the Cominform, Tito’s excommunication and the show trials deserve deeper analysis. Stalin and his chief ideologue, Andrei Zhdanov, designed it as a select club, excluding major parties such as those of China and Greece. But French and Italian communists were represented, an indication that Stalin had not dismissed expansion into Western Europe.

Gellately’s gripping narrative ends with Stalin’s last major public appearance in October 1952, at the 19th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party. Far from admitting that the nuclear age had changed priorities in foreign policy, the tyrant was adamant in advocating a bellicose course. At that moment, surrounded by worldwide adoration, he was worshipped not only as the greatest military genius of all time but also as Marx’s and Lenin’s equal as a coryphaeus of revolutionary science. Gellately is right: nothing mattered more for Stalin than being recognised as the fourth sword of Marxism, the theorist of communist society, economy and culture. In 1938, his main preoccupation, in addition to signing hundreds of death warrants for “enemies of the people”, was with editing the “Short Course” of the Communist Party’s history - in fact, a political demonology meant to show how he rescued Lenin’s party from plots by Trotskyists and others. But by 1952, he spent most of his time in discussions related to a treatise of socialist economy, manically editing texts provided by trusted sycophants.

It took only a few weeks after his death for his successors to start de- Stalinising the country. This was not however a revolutionary break with his delusions but rather an attempt to give up the most irrational features of the dictatorship. In the ensuing decades, Gellately rightly argues, “Soviet leaders and ruling elites continued to articulate their positions very much along the lines he set, until the whole edifice of the once-mighty Red Empire came crashing down”.

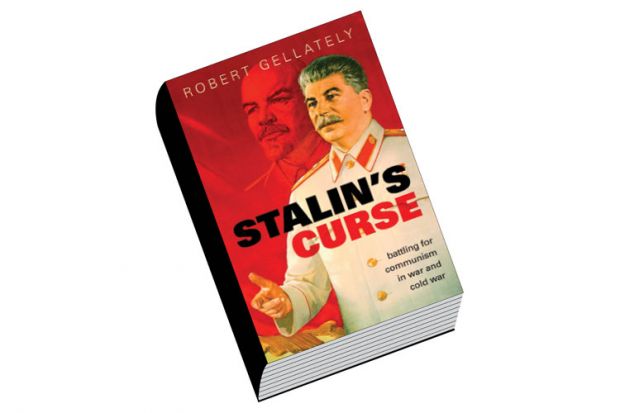

Stalin’s Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War

By Robert Gellately

Oxford University Press, 496pp, £20.00

ISBN 9780199668045

Published 5 March 2013

The author

“I am a great believer in the value of being faithful to the facts, perhaps part of my Newfoundland heritage,” says historian Robert Gellately, who was born in 1943 in St. John’s, capital city of an island colony that would not become Canada’s tenth province for another six years.

“My research has been driven by seeking to understand and explain the unsettling and challenging aspects of history. I never tire of trying to tell the story of how things really happened.”

Now the Earl Ray Beck professor of history at Florida State University, he lives in Tallahassee, Florida, with his wife and fellow academic Marie Fleming. Both, Gellately admits, “were delighted to leave snow shovelling behind”. But, he adds, “I still feel the pull of my native land. I can never repay my debt to Memorial University there, for opening the world of learning to me.

“I was anything but a studious child, but I did like to read and think for myself. My general interest in history and world affairs brought me to Memorial. There I was inspired by a number of professors, above all by Gerhard Bassler, who introduced me to Russian and German history.

“For me and many of my fellow students at Memorial, the natural next step was taking a PhD in Britain,” he recalls. “I attended the London School of Economics, which was and remains a fabulous hive of intellectual activity.”

Were he to live anywhere else, he says, he would choose Berlin, “now a centre of learning and home to the German Federal Archives. There are also easy connections from Berlin to Central and Eastern Europe.” Of his leisure pursuits, Gellately says, “For many years my passion was for downhill skiing, and I’ve tried the steepest mountains in Europe and North America. Living in the South makes that hobby impractical, so I’ve taken almost as fanatically to the gym and the weight room. It keeps me sane, or so I tell myself.”

Karen Shook

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?