When the novel coronavirus first hit Singapore in January, universities were two to three weeks into a new semester. As the number of cases climbed, university administrators grappled with challenging questions of protocol and pedagogy.

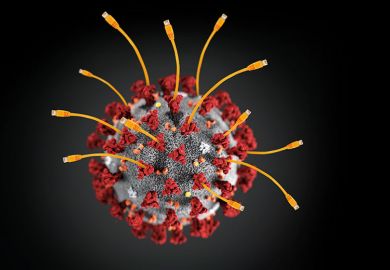

Today Covid-19 knocks on doors worldwide, and universities everywhere face unprecedented challenges. One of the strategies embraced by many universities has been to migrate classes online.

For those of us who are accustomed to teaching face-to-face, this idea is unsettling, and I have had many email enquiries about how to make a swift transition to online teaching. The most common questions are: “How can we facilitate interactive, student-to-student learning in an online setting?” and “If our courses move online, how do we carry out online assessments without risking cheating and plagiarism?” Here are some ideas.

Promote peer-to-peer learning

Migrating lectures and even faculty-student interaction online is not that challenging. But encouraging student-to-student learning is a more daunting project, particularly in smaller colleges where students expect a more dynamic, less hierarchical, dialogue-driven format.

Fortunately, online platforms such as Zoom and the Minerva Project’s Forum offer mechanisms for small group conversation and student-to-student verbal and visual collaboration in addition to facilitating teacher-student dialogue.

Course management systems such as Canvas offer text-based interactive mechanisms including discussion groups and blog-style formats.

For someone like me, who relies heavily on physical movement and body language in teaching, the online experience is not nearly as fulfilling, but these online formats are a valuable supplement, and even complement, to face-to-face learning.

Can we design cheat-proof assessment?

As the Covid-19 situation becomes more widespread, students could be taking mid-term and final exams from the comfort – and containment – of their dorm rooms or family homes.

As with all assessment, I have encouraged faculty to align assessments closely with intended learning goals and help students develop the skills to complete these assessments successfully. If courses move online, learning goals themselves, as well as our methods of assessment, may need to shift.

Beyond the obvious technological aids such as Turnitin, which helps detect plagiarism, there are pedagogical and design strategies that make it harder for students to simply copy and paste from online sources or each other.

One strategy is to avoid easy-to-cheat formats such as multiple choice or objective (simple right-or-wrong answer) questions. Instead, ask complex, specific questions such as: “Define a collective action problem and provide an illustration that is specific to your family context.” That certainly isn’t something they are likely to find on Wikipedia.

A second strategy is to diversify assessment formats, relying less on essays and written exams and instead embracing oral exams using Zoom or Skype, or having students produce podcasts, YouTube videos, posters or Prezi presentations that can be shared online.

A third tactic is to design assignments with process questions, in which students reflect upon and describe the experience of writing the essay or taking the exam. Not only do these kinds of questions promote metacognition, they may deter cheating.

Lean into it

Rather than trying to set a “cheat-proof” test, instead deliberately design open-book, open-source or even collaborative exams. After graduation, students will almost never be told to produce work in total isolation.

We can design assignments that mirror and prepare students for the “real world”, where they will have books, internet resources and colleagues for help.

Empower students to use their own voice

Academic integrity violations often emanate from self-doubt, in turn leading to panic and then cheating. Helping students build their self-confidence reduces this risk.

We can build skill and confidence by being transparent with students about our learning goals and assessment strategies. For example, integrate learning activities that allow students to practise a particular assessment format before asking them to produce work for a higher-stakes final assignment.

Lecturers can also help by normalising struggle, sharing their own experiences of failure and growth to encourage students to develop their own voice rather than plagiarising another’s.

Let it go

Sometimes we spend more time thinking about how to minimise cheating than how to enhance learning. Assessment activities are ideally also learning activities – opportunities for students to solidify and deepen their knowledge. If assessment design promotes learning but creates some small opportunity for cheating, sometimes that is unavoidable.

So one option is to just let it go. Start from a position of trust in your students and tell them that you hold them in high regard and expect them to act honourably. You could even have them sign an honour statement to that effect. Then, choose to design your assignments around learning and worry less about preventing cheating.

Catherine Shea Sanger directs the Centre for Teaching and Learning at Yale-NUS College in Singapore, where she is senior lecturer in global affairs. She is co-editor of Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education: Lessons from Across Asia.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: How to teach in a time of coronavirus

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?