As head of the faculty union at the University of Florida, Paul Ortiz often finds himself channelling his inner whale hunter.

Florida, after all, is arguably at the centre of political anxiety in US higher education over where things might be headed. The state’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, has been persistently ranked as a top contender for the US presidency in 2024, buoyed in no small part by his emergence as the unofficial leader-in-waiting of Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again movement, characterised by its anti-intellectual crusade.

For students and faculty at Florida’s 40 state colleges and universities, that has meant confronting a variety of DeSantis policy initiatives that strike at the heart of academic freedom and expertise. These include banning courses that explore the nation’s historic and current battles against racism and gender-related bias; barring faculty from serving as expert courtroom witnesses against the governor’s own political positions; installing fellow ideologues on university governing boards and increasing their powers of institutional and curricular control; and challenging vaccines as a legitimate response to Covid.

Ortiz, a professor of history at the state’s flagship public institution and president since 2020 of his campus chapter of the United Faculty of Florida union, alternates between defiant talk about how well he and his colleagues have resisted the DeSantis agenda and sombre recognition that they probably can’t keep it up much longer.

In his more resigned moments, Ortiz seeks inspiration from the crew of the whaling ship Pequod in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick: “You have Captain Ahab at the helm. You know things are not right. You know the voyage isn’t really going well. You know that the end is probably not going to be where you want to be. But, at the same time, your job is to go out and kill whales, and so you do it.”

Union heads elsewhere in the nation might also want to seek Melville out in their campus libraries before November 2024. DeSantis just won a runaway re-election as governor – by a 3-2 margin of victory in a state where registered Republicans barely outnumber Democrats – prompting Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post, previously a staunch Trump supporter, to label him “DeFUTURE”. Subsequent polling has shown DeSantis to be substantially more popular among Republicans nationwide than Trump in a match-up for their party’s presidential nomination.

All that has made a DeSantis candidacy seem increasingly inevitable – particularly given Trump’s mounting legal jeopardy. This has created the spectre of a US president who is as extreme a partisan as Trump – but a lot smarter about getting things done.

“DeSantis has a similar ideological state and ideological focus,” notes Alan Singer, professor of teaching, learning and technology at Hofstra University, New York. “But he’s much more competent, and much more systematic.”

Most people within US universities regarded the end of Trump's presidency with relief after four years of attacks on immigration, the science budget and expertise more generally. So how much danger would a DeSantis presidency pose to universities nationwide?

For the mounting number of experts increasingly distracted by the prospect, there is no single answer. Among their more reassuring thoughts is the fact that in the US, education policy is much easier to control at the state and local levels than the federal, while a US president has a lot more pressing national and global problems to spend time on. Less comforting, though, is the understanding that the federal government does hold critical powers over university funding and accreditation, that the US president’s ability to influence public impressions is immense, and that DeSantis appears unusually committed to the topic of higher education, well beyond its convenience as a tool to excite his political allies.

“This is an administration that seemingly wakes up every day or every week and comes up with some new way of targeting educators,” says Jeremy Young, the senior manager for free expression and education programmes at PEN America, a national association of writing professionals focused on academic freedom issues. “And I certainly would expect that kind of energy to continue.”

DeSantis was born in 1978, the first of two children of working-class ethnic Italian parents living in northern Florida. He attended Yale University on a baseball scholarship, became the Yale team’s star player and graduated with a degree in history. He then served in the US Navy, with postings that included Guantánamo Bay and Iraq, and graduated from Harvard Law School. From there, he worked as a federal prosecutor, published a book critical of President Barack Obama, won a seat in the US House of Representatives, and then used Trump’s backing to win election as Florida’s governor in 2018.

The general pattern across the US is that states with conservative governments spend less on education and have worse outcomes. Florida, though, appears something of an outlier. A favourite talking point among the state’s educational and political leadership is the US News & World Report ranking, which lists the University of Florida among the top five public research universities in the US. The ranking also scores the state first overall, on a combination of measures that include tuition and graduation rates at public institutions.

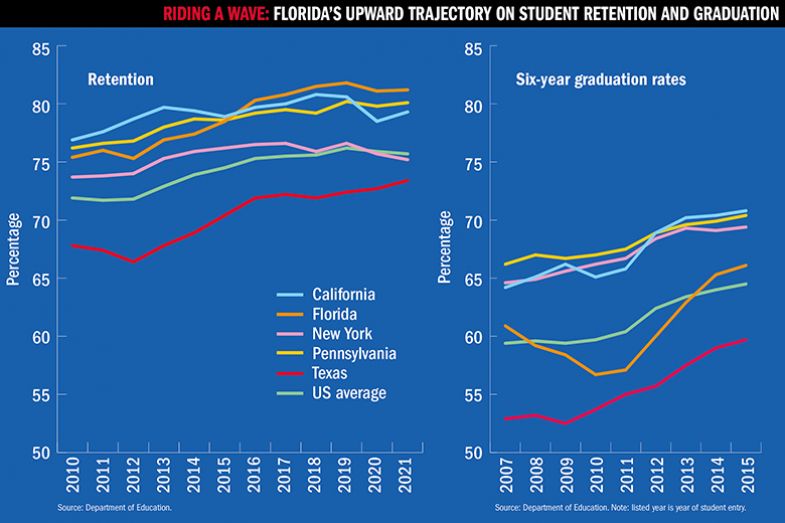

While the US News analyses are much maligned across higher education, some of Florida’s underlying numbers appear genuine. The state’s public universities are significantly ahead of US averages on both student retention and graduation, and they have been for well over a decade, according to figures compiled for Times Higher Education by the US Department of Education. By 2012, Florida’s four-year institutions were graduating 73 per cent of their first-time, full-time bachelor’s degree-seeking students within six years, compared with the US-wide average of 64 per cent. And by the autumn of 2021, the federal data show, slightly more than 81 per cent of such students at Florida’s public universities were returning to their classes from the previous academic year, compared with the average US retention rate of just below 81 per cent (up from 76 per cent the previous year).

The state also ranks well on affordability, with the College Board’s annual report showing Florida’s public universities charging the lowest price in the nation (counting student aid) for a bachelor’s degree. Florida also claims four of the 10 best-rated college towns in the US, according to this year’s annual survey by WalletHub (based on “32 key indicators of academic, social and economic opportunities for students”).

The state’s record on research is more mixed. US universities dominate THE’s World University Rankings, which emphasise scientific achievement, yet no Florida institution is within the top 150. Separate THE analyses show Florida’s universities ahead of national averages in areas of volume, such as production of doctorates, research publications and industry income, but below average in areas that include research and teaching reputation and international co-authorship.

The state’s record on equity appears especially problematic. Two of its top-ranked campuses – the University of Florida and Florida State University – have lost a combined 3,000 low-income students since 2014, even while their overall enrolments have surged. The shift is attributed by experts to factors that include the state’s push for gains on the US News measures – which reward institutions that reject large shares of their applicants – and a scholarship programme, funded by state lottery proceeds, that is seen as disproportionately benefiting students from wealthier parts of the state.

More fundamentally, says F. King Alexander, a Florida native who has led four different US colleges and universities, the categories where the state posts eye-catching numbers are mainly a function of its large population – the third-biggest in the US. Florida has fewer universities than Michigan, yet has twice the number of residents, Alexander notes. That has left it with four campuses of more than 50,000 students. Such unusually high demand, he says, gives Florida an environment of high selectivity in admissions, high SAT scores among admitted students, and plentiful tuition revenues.

“The reason [Floridian universities] are rising is because there’s so many people applying, and they’re turning down so many people,” Alexander says. “They’re living on scale.”

Either way, the situation has handed DeSantis a powerful platform for challenging fundamental understandings of success in higher education, while arguing that his brand of management – or interference, in the eyes of many academics – is actually a winning strategy.

The US News ranking, the University of Florida crowed right after its latest release in September, “demonstrates the return on the investment in UF’s students, faculty and staff by Gov. Ron DeSantis, the Florida legislature, the state’s congressional representatives, the board that oversees the state university system and the UF Board of Trustees”.

That reference to the trustees strikes some wary Florida faculty as especially noteworthy. During several of his attempts to stifle academic freedom, the governor hit hard resistance from institutions and the courts. University governing boards appear to offer him a way around them.

One of DeSantis’ clearest losses came in late 2021 when the University of Florida, under pressure from his office, blocked three of its political science professors from providing expert testimony in a lawsuit challenging a new DeSantis-backed state law limiting the ability of some residents to vote. After the professors made their exclusion a major public embarrassment for the governor, the university backed down.

Another setback involved the new Florida law known as the “Stop WOKE Act”, which seeks to impose limits on what schools and workplaces can teach about the nation’s historical and ongoing struggles with racial division. A federal judge in November blocked it from taking effect at public universities, with a ruling in which he recited a warning against totalitarianism – about clocks “striking 13” – from George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Meanwhile, less than 1 per cent of Florida’s 2 million students responded to a survey ordered by DeSantis and state lawmakers, faculty and staff, apparently trying to confirm allegations that colleges and universities proselytise for politically liberal attitudes. Nearly 10 per cent of faculty and staff responded, but mostly those who described themselves as conservative.

That’s where the trustees come in. Florida law gives the governor extensive authority to appoint members of the governing boards of both its public universities and the state system of higher education. DeSantis not only has appointed to those boards numerous members regarded as his partisan allies but has also pushed the state legislature for definitional changes that would give the boards more direct institutional control in areas that include hiring faculty, defining tenure and determining acceptable curricula.

One the most visible recent outcomes of that strategy was the appointment of US Senator Ben Sasse to the presidency of the University of Florida – with the behind-the-scenes guidance of DeSantis’ chief of staff. The trustees’ approval of Sasse provoked extended campus protest over the Nebraska senator’s socially conservative positions, especially his declared opposition to same-sex marriage. DeSantis also installed a top Republican ally from the state Senate, Ray Rodrigues, to serve as Florida’s chancellor for higher education.

But DeSantis has not given up on influencing universities by other means. In late December, for instance, all 12 four-year public universities in Florida were asked by DeSantis’ office to report their “expenditure of state resources on programs and initiatives related to diversity, equity and inclusion, and critical race theory”. Measures to clamp down on that expenditure – a particular bugbear of right-wing Republicans – may be expected to follow.

While many Republican governors have attempted to rein in universities in their states, as they see it, DeSantis strikes some observers as far more eager to test boundaries than others have been.

A cautionary example, says Young of PEN America, is the fact that the legislatures in at least 19 states have passed some version of an educational gag law similar to Florida’s Stop WOKE Act. But, usually, the governors accept some publicity for signing the bill, then don’t spend much time talking about it. DeSantis, he says, is different.

“There really is a distinction between what they’re doing in Florida and what’s going [on] elsewhere,” Young says. “The kind of sustained push to keep this in the news, to keep finding examples of teachers and programmes to censor, to dial up the chilling effect to 11, is fairly unique to Florida.”

And the White House and its congressional allies have plenty of levers of power over universities if they choose to use them. The federal government’s major funding outlays on higher education include about $50 billion (£40 billion) a year on scientific research and about $30 billion a year for the Pell Grant programme for low-income students.

At the moment, such huge amounts appear politically untouchable. Trump threatened at one point to challenge federal funding and the tax-exempt status of universities, to counter their “radical left indoctrination”, but went no further than that. But Young, for one, doesn’t even want to think about how far DeSantis might try to go.

“I can 100 per cent imagine things being done at the federal level” by a president such as DeSantis, he says. “The main reason I don’t want to speculate is that I don’t want to give anyone any ideas.”

DeSantis probably doesn’t need the help. Beyond its basic ability to cut higher education funding, the federal government can also wield major control over institutions through bureaucracy. Universities need the approval of a federally recognised accrediting agency for their students to be eligible for financial aid, making it a pressure point as crucial to institutions as direct federal funding but one that is far more difficult for the public to follow. As such, experts note, accreditation affords a motivated government wide potential for rewriting the terms of institutional behaviour.

And DeSantis has already shown that he understands that power and considers it well worth trying to shape and control. He signed a law this past year requiring Florida’s public colleges and universities to regularly change their accrediting agencies, after the University of Florida’s longtime accreditor, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, began investigating the institution for blocking the courtroom testimony of the three political science professors, amid suspicions that it had violated academic freedom and succumbed to “undue political influence”. The investigation ultimately cleared the university.

Two years away from the 2024 election, experts are wary of predicting the specific options a DeSantis administration would choose. Michelle Dimino, deputy director of education at the centre-left thinktank Third Way, remains convinced that President DeSantis’ attentions would be redirected elsewhere: “His capacity to have a heavy hand in post-secondary policy as president would pale in comparison to his current scope of influence on public higher education within Florida, and his interest in reform likely would, too.”

John Thelin, professor of higher education and public policy at the University of Kentucky, agrees. Politics at the state level is markedly different from the national level, he says, given its much more personal nature. The close relationships between state-level politicos and their universities have many complicated layers, “at times, mutually congratulatory; at other times, the state university is a convenient target that enlists pseudo-populist support,” he says.

Meanwhile, David Weerts, a professor of organisational leadership policy and development at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, believes that academia might just emerge from a DeSantis presidency having endured nothing worse than a federal commission that highlights Republican talking points on viewpoint diversity on college campuses. “It is harder to get traction on higher education reforms at the federal level,” Weerts says, “so I don’t think that he will spend a lot of time pushing some major policy initiative in the realm of higher education.”

But another longtime analyst, Timothy Kaufman-Osborn, emeritus professor of politics and leadership at Whitman College, is far less confident of avoiding harm. He finds it hard to believe that DeSantis would give up on a topic of clear interest once he gets inside the White House. Under a DeSantis presidency, he says, US academics should expect the dogged pursuit of an anti-education agenda “through whatever means are available to him”.

Even if a President DeSantis does largely forgo or fail on major legislative or administrative action against higher education, Kaufman-Osborn and others point out, he’s almost sure to keep pushing his party’s long-running process of normalising – for both the public and professors – the corrosive idea that academics are motivated by goals other than pursuing objective truths and educating students the best they can.

By that measure, DeSantis would be bolstering conservatives in a public relations war they already appear to be winning. Americans in recent years have increasingly embraced the perspective that higher education should be primarily, if not exclusively, an exercise in training people for jobs – and not about creating well-rounded citizens and creative thinkers inclined to question the nation’s various structural shortcomings.

This Republican-led campaign dates back at least to the 1960s, when Ronald Reagan, as governor of California, engineered the firing of Clark Kerr as president of the University of California over Kerr’s tolerance of pro-free-speech protesters at the University of California, Berkeley, amid a campus ban on political activities that restricted students’ ability to protest against the Vietnam War and in favour of civil rights. By Trump’s presidential victory in 2016, polling showed that Republican voters had retreated from their assessment that college generally has a positive effect on society. And federal data show that between 2010 and 2020, liberal arts majors have lost the most students, while health, sciences and business fields have gained the most.

DeSantis has carried on that tradition, mixing tangible policy prescriptions with rhetorical assaults on social equity and scientific understanding. His antics have included honouring a University of Virginia swimmer from Florida as the “rightful winner” of a championship race after she finished second to a transgender athlete. And he has also reversed his Trump-era support of Covid vaccines, urging a criminal investigation of whether pharmaceutical companies overstated their value.

The significance of a President DeSantis creating and reinforcing negative attitudes about higher education should not be underestimated, says Barrett Taylor, an associate professor of higher education at the University of North Texas.

“Even if we stipulate that some of the formal policy changes [that DeSantis has introduced in Florida] are going to be undone by courts or by subsequent administrations – and some of them have not been as far-reaching as we might have feared – just that amping up of the rhetorical attack on higher ed and its trustworthiness is a pretty substantial policy change. To hear those things coming from a presidential candidate, or a president, would be even more concerning than to hear it from a governor,” says Taylor, author of the recently published book, Wrecked: Deinstitutionalisation and Partial Defenses in State Higher Education Policy.

“Each time a new cycle of this rhetoric passes through, and some years have gone by, the ability of colleges and universities to respond weakens a little bit,” he adds.

Hofstra’s Singer concurs. “A DeSantis victory would have a very intimidating impact on college professors,” he says. “That would be the biggest impact.”

Ortiz already sees that impact on the University of Florida campus. On one level, the faculty union leader is impressed by the spirit he sees among his colleagues. State funding has been tight, he says, but it has taught Florida faculty to be even more aggressive about finding outside sources. In the political arena, he says, key victories for faculty and students include the strong campus-wide support of the three political science professors, as well as the peaceful but overwhelming protest against a campus speech by neo-Nazi Richard Spencer shortly after he helped lead the deadly 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Ortiz has lectured at institutions including Stanford, Yale and UCLA, and he insists that Florida’s students, faculty and staff are as good as those he’s seen anywhere. “We have worked under so many distractions, especially in the last few years,” he says. “We keep our heads down, and we keep working.”

At the same time, Ortiz sees some Florida faculty giving in, voluntarily silencing themselves rather than risking public criticism or worse, as students obey partisan calls to record their lectures and report any comments that might make good fodder in the nation’s acerbic culture wars.

“The fight is to keep the integrity of intellectual freedom intact. To me, that’s the most important thing,” Ortiz says. “If we lose that, we lose everything – once faculty and students begin to say things like, ‘Well, what would Governor DeSantis think about this syllabus or this research grant proposal?’”

“We’re holding the ship right now,” Ortiz says, in another reference to Moby-Dick. “I don’t know how much longer we can deal with these distractions, to be honest with you.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?