For Beverly Daniel Tatum, undergraduate life at Wesleyan College in Connecticut was an “immersion experience” largely devoted to exploring her black identity.

Although she majored in psychology, she “took a lot of African American studies courses – history, literature, religion, even Black child development”, she writes in her celebrated book, Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race. “I studied Swahili in hopes of traveling to Tanzania, although I never went. I stopped straightening my hair and had a large Afro à la [political activist and academic] Angela Davis circa 1970. I happily sat at the Black table in the dining hall every day.”

Although black students were very much in the minority, Tatum goes on, she “can’t remember the name of one White classmate”. Because she was focused on forging “a positive sense of self based on an affirmation of [her] racial group identity”, white people were, at least for a while, “simply irrelevant”.

The process, she suggests, is a bit like learning another language, often best achieved through a period of total immersion. And, although the “cultural symbols” black students embrace today may be different from those of her generation, they often want to follow a similar path.

Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? was first published in 1997, but she decided to update it in 2017, Tatum tells Times Higher Education, to “recognise changes in populations, the field of psychology, the political environment and, unfortunately, growing polarisation”. The new edition proceeded to spend 11 weeks on The New York Times best-seller list last summer, at a time of much anguish about race relations, and is now published in the UK by Penguin Books. Its sharp insights draw on close to four decades of reflection and research and offer powerful lessons for universities everywhere trying to face up to legacies of racism.

Back in 1980, while still working on a PhD at the University of Michigan on “the experience of black families in predominantly white communities”, Tatum was asked to take over the teaching of a “very interactive and experiential” course called Group Exploration of Racism at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“It was new territory for my students,” she claims, “and some said on evaluations: ‘Why did I have to wait until I was a senior, about to graduate, before I had meaningful conversations about this important topic?’” So when she moved on to become a professor of psychology at Westfield State College and then Mount Holyoke College – both predominantly white institutions in Massachusetts – she continued teaching a similar course, now titled The Psychology of Racism.

Tatum went on to serve as president of Spelman College in Georgia, one of only two women-only historically black universities, from 2002 to 2015. There, she recalls, there was “a required first-year seminar on Africans in the Diaspora and the World, a sort of ‘great books’ course with material created by African and African American scholars. For many of the students, it was the first time they had exposure to that sort of information because it is typically not included earlier in their education. It is empowering for them to think: ‘I never knew people who looked like me were writing these things and had these ideas.’ Could they have learned it in high school? Sure – if someone had offered it!”

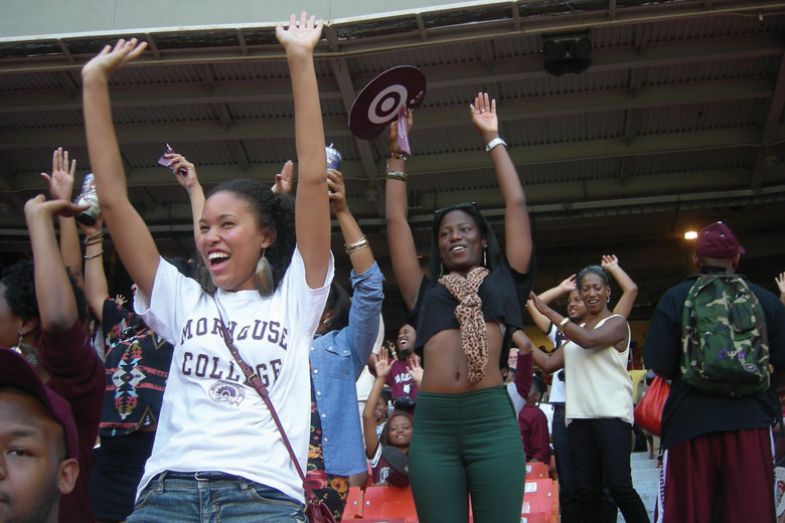

An intense period of racial identity formation often takes place at university, Tatum points out, “because it’s the first time people really have choices about what they are going to study and read. Some black college students will talk about not having really had a peer group at their local high school that had the same interests.”

As her own experience at Wesleyan illustrates, students will always want to get together to explore issues of racial identity. “If the institution understands it is a positive thing and acknowledges and supports that development, students appreciate it and feel affirmed,” she says.

This whole issue, however, was for a long time something of a blind spot for psychology as a discipline, Tatum contends.

When she taught courses in child development, she would always “look at the textbooks to see if they contained anything about racial and ethnic identity development”. Although they certainly touched on adolescent identity development more generally, this particular aspect was – and remains – largely ignored. This may well be because white people generally don’t reflect on their white identity, she believes – and, despite improvements, black psychologists are still very much in the minority.

Nonetheless, Tatum also believes that “there are increasing numbers of white social psychologists trying to understand the mechanism of racism, stereotyping, biases and how they are transmitted – and developing the groundbreaking idea of ‘stereotype threat’, a term coined by the black psychologist Claude Steele”. This work has some very direct implications for teaching in universities.

Stereotype threat in education arises from the ways that negative stereotypes about the performance of a particular group can themselves contribute to underperformance by inducing anxiety. “Fundamentally,” Tatum explains, “what we know as psychologists is that the situational context shapes behaviour in ways we often don’t acknowledge. When someone is behaving in a certain way, I may think it’s because of some characteristic of that person. I won’t necessarily see how it is shaped by the circumstances they find themselves in. The tendency to explain people’s behaviour in terms of their individual characteristics, rather than their situation, is what psychologists call the fundamental attribution error.”

This phenomenon is particularly relevant in the context of race relations, Tatum goes on. “If a student is doing poorly in an exam, [people assume that] it must be because he is not very smart – rather than because he didn’t get enough sleep last night or because he’s having a bad day. White students are more likely to get the benefit of the doubt compared with students of colour, particularly black students, because of the stereotypes that exist.”

The behaviour of teachers is crucial here, according to Tatum: “If I make the assumption that it is possible for every student in my class to learn and be successful, I will behave differently from if I assume some students are not capable. I will respond to a student with high expectations and communicate verbally and non-verbally that they are capable of meeting those expectations and that I’m going to give them the feedback they need. Then students often deliver a much higher performance than when they perceive that little is being expected of them.”

Black students, in particular, have “often learned that people don’t expect much from them”, so when they encounter someone who does, the effect can be akin to that of “water in a parched land: so wonderful that it gives them an extra boost”.

In her book, Tatum cites research by Steele and his Stanford University colleague Geoffrey Cohen indicating that black students respond particularly well to what they call “wise criticism”, which communicates “both high standards and assurance of belief in the student’s capacity to reach those standards”. The book also describes another project, by Joshua Aronson, Carrie Fried and Catherine Good, that considers the deep impact of conveying to students that intelligence is something malleable rather than fixed. This shifts the attitudes of black students from “the anxiety of proving ability in the face of negative stereotypes to the confidence of improving with effort despite the negative stereotypes”, Tatum writes.

Given her eminence in the field, Tatum reports that “many college presidents reached out after the George Floyd incident saying they were thinking about how to be more inclusive institutions, to expand representation in our curricula for students who feel left out”. She also had the opportunity to lead a week-long seminar sponsored by the Council of Independent Colleges to which member institutions could send teams to “develop an intervention they could institute back at their campus”. Key themes that emerged included “inter-group dialogue”, changing curricula to include courses such as the Psychology of Racism, “better supporting student organisations focused on identity development” and “building coalitions across lines of difference”.

Yet perhaps the most striking chapter in Tatum’s book is the one on “The Development of White Identity”.

“Even the phrase ‘white identity’ generates anxiety for some people,” she admits, “because it sounds like you are talking about the Ku Klux Klan or white supremacists. For many people, thinking about themselves as white is simply not something they do, because it is not brought to their attention…Reflection is often an uncomfortable process, which makes white people guilty, angry and sad, but rarely happy.

In her chapter on this topic, Tatum includes much vivid material from the courses she has taught, both to students and teachers on professional development courses. Many white people react with anger and victim-blaming as they are forced to reconsider their belief in meritocracy and to accept that it is a luxury to think of oneself as an individual (rather than as a member of a stigmatised group). Even students who genuinely “wanted to step off the cycle of racism” feel pressure from their communities to “get back on”.

Fortunately, Tatum adds, people who are basically well-intentioned seem to be able to “get past the bias…when expectations for appropriate behavior are clearly defined”. And many find sustenance in learning about “White individuals who have been engaged in antiracist activities”.

There are some fairly obvious challenges in scaling up such courses, aimed at small and self-selecting groups of students, into wider societal initiatives. Yet Tatum urges universities to “take advantage of the diverse perspectives of their students: something wonderful that typically can’t be found outside the college or university. Many people encounter that variety only there – and perhaps in the military. We miss out if we don’t create those learning opportunities.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: ‘Black students learn people don’t expect much from them’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?