It is no secret that the Gulf states have been pumping huge amounts of money into higher education as part of a long-term bid to shift their economies away from a dependence on natural resources.

This has been exemplified by the approach of Qatar. Through the Qatar Foundation, the small, oil-rich state has ploughed billions of dollars into its Education City site in Doha over the past 20 years, in a successful bid to attract some of the world’s leading universities to open campuses there.

However, the future of this model has been shaken to the core by the diplomatic rift that has erupted in the region between Qatar and several other Arab countries – including its powerful neighbour, Saudi Arabia – ostensibly over claims that Qatar has funded Islamist groups in the Middle East.

But how much damage will be inflicted on universities in Qatar, and in the region in general, by the blockade imposed on the country since last summer? The latest Times Higher Education Arab World University Rankings give some clues.

Saudi Arabia leads the way in the region, with King Abdulaziz University heading the table and three others in the top 10. The United Arab Emirates, an ally of Saudi Arabia in the diplomatic row, also has a strong presence, with Khalifa University ranked second and United Arab Emirates University ranked fifth.

Qatar has only one institution, Qatar University, in the list. But it is ranked third: up from fifth last year. And the reason that there are no other Qatari institutions in the ranking is simply that most of the institutions that have a presence in Education City are in effect overseas campuses.

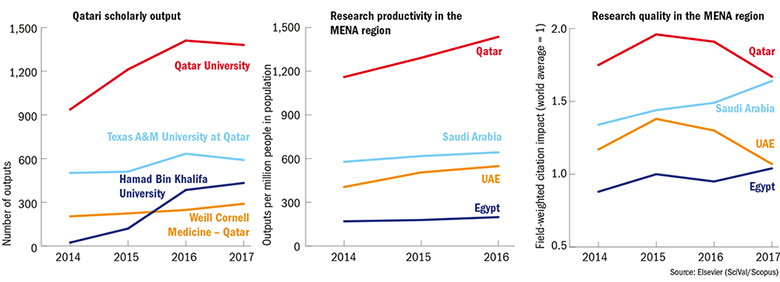

Although Hamad Bin Khalifa University is Qatari, it is still too small in research terms to enter the ranking. It is also mainly postgraduate and only universities with undergraduates can enter (a rule that also excludes Saudi Arabia’s flagship research university, the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST): the country’s third-largest producer of research papers). However, a sense of Qatar’s real research prowess can be gained by combining the research output produced in 2017 by Hamad Bin Khalifa (which was only founded in 2010) with the two Education City institutions for which separate data exist in Elsevier’s Scopus bibliometric database – Weill Cornell Medicine – Qatar and Texas A&M University at Qatar. In terms of volume, they now almost equal Qatar University’s own output.

Qatar’s overall research output (excluding the Education City campuses not indexed by Scopus) is understandably lower than that of its larger neighbours. But, per capita, it produces more than Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the UAE – and that output has also been increasing at a faster rate.

The field-weighted citation impact of Qatar’s research, a measure of quality that allows for fluctuations in citation rates by year and by subject, has also been higher than that of its rivals – although Saudi Arabia has been improving and, spearheaded by King Abdulaziz University and KAUST, virtually equalled Qatar in 2017.

Research outputs compared

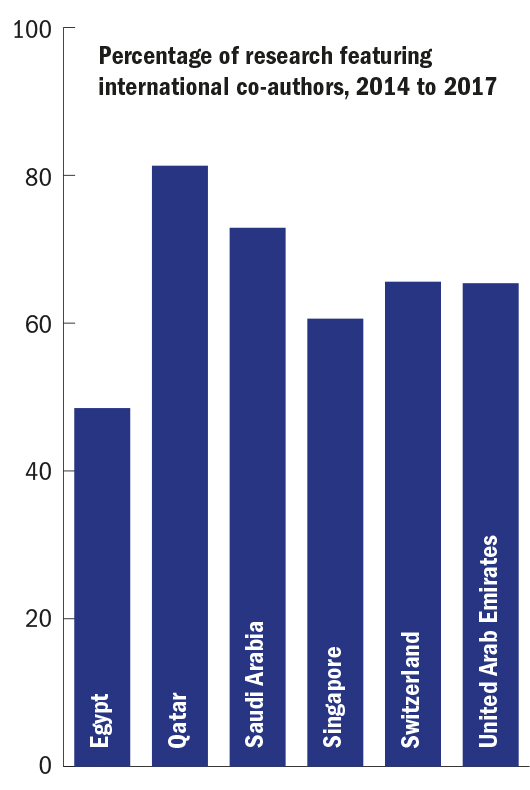

The data also illustrate how Qatar, the UAE and even Saudi Arabia have been driving their scholarship forward through internationalisation. In all three nations, more than 60 per cent of research between 2014 and 2017 featured at least one co-author from outside the country. The impressive nature of this statistic becomes clear when you consider that the international collaboration rates for Switzerland and Singapore – two of the most open research nations in the world – were both lower than those of Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

Percentage of research featuring international co-authors

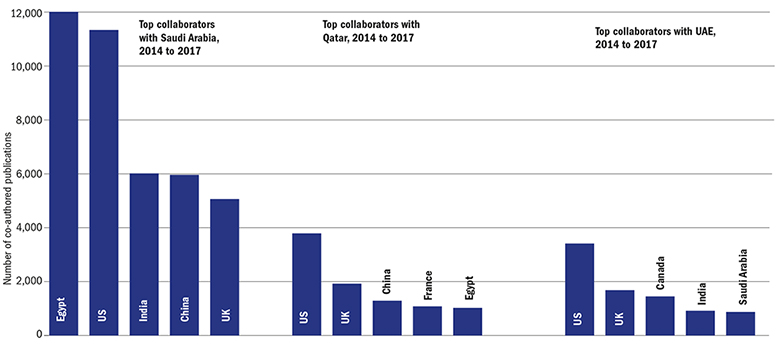

At the same time, the collaboration patterns are very different in each Arab nation. Saudi Arabia’s top international collaborator is Egypt, followed by the US, India and China; the UAE and Qatar do not even figure in the top 20.

However, for Qatar, Saudi Arabia is the sixth most important collaborator in terms of the volume of co-authored papers, after the US, UK, China, France and Egypt. The UAE has a similar pattern, except that India is a more important collaborator than China.

Top collaborators across the region

Hilal Lashuel, former executive director of the Qatar Biomedical Research Institute at Hamad Bin Khalifa University, does not think that the boycott of Qatar will hit the country’s research infrastructure particularly hard since, as the data illustrate, “the level of collaboration between Qatar and blockade countries is very minimal”. Moreover, “none of the [research] activities in Qatar is dependent on collaboration with these countries”, adds Lashuel, who is currently associate professor of neuroscience at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland.

However, the crisis is still a “major setback” for science in the region. “Despite the lack of strategic collaborations or extensive scientific interactions between scientists from Qatar and the blockade countries, there was a genuine interest in exploring collaboration, coordinating activities and sharing experiences, especially in the field of genomic and personalised medicine,” Lashuel says. “Several entities” in Qatar, including the Qatar Foundation, the Qatar Biobank and the Qatar Genome Programme, had organised conferences on these topics and invited experts from countries such as Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. Delegations from Qatar also visited Saudi Arabia – principally KAUST – “to explore collaborations and share their experiences in establishing competitive research programmes” in the Gulf region.

“I believe that many of these actions were also driven by the fact that [the Gulf countries] finally realised that many of the major health, environmental and security challenges they face are similar, and unique to the region, and that finding sustainable solutions will require financial resources, scientific infrastructure and human capital that goes beyond the capabilities of the individual countries,” Lashuel says. “At the level of the scientists, there has always been great interest in collaborating and sharing resources and experiences.”

There is some evidence that humanities academics in the blockading countries are finding it harder to work with counterparts in Qatar. Mehran Kamrava, director of the Center for International and Regional Studies at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Relations in Qatar, says that it was “relatively easy before the blockade (and relatively frequent) for us to collaborate with scholars” based in the boycotting countries. But while the institution has continued to work with some scholars based in Egypt, efforts to collaborate with academics from the UAE have been “hit and miss”.

“Some have had no difficulty coming and being a part of our research initiatives, or have not feared any repercussions, while others tell us that their institutions cannot guarantee that their residency permits would be renewed if they travelled to Qatar,” Kamrava says. And while Georgetown has not had occasion to try to work with academics from Bahrain or Saudi Arabia since the blockade was imposed, the potential repercussions for any researchers from those countries tempted to collaborate with Qatar leads him to assume that any invitations by Georgetown would be declined.

For its part, the Qatar Foundation is concerned that the research ecosystem that it believes it has helped to foster in the region will be harmed in the short term by the blockade. However, Omran Hamad Al-Kuwari, the foundation’s executive director, is still optimistic that the need for Arab nations to find common scientific ground will win out.

“Everyone loses from [the involvement of politics], whether it’s education or research, and we hope that [this situation] is short-lived and we can go back to collaborating,” he says. “The best thing we can do is stick to our plans, keep focused and moving forwards and try to be a positive player in all this.”

Echoing Lashuel’s point about the region’s shared problems, he cites water scarcity and “issues related to pollution and climate change” as concerns on which there is “an opportunity for us to collaborate”.

The large research capacity that Qatar has built up, and the connections to Western universities that it has through Education City, mean that its own scholarship should be insulated from immediate harm by the boycott. But, as Lashuel points out, the blockade could harm not only Qatar but all the Gulf nations if it hits “the recruitment of talented and established scientists and students” from outside the region.

Christopher Davidson, reader in Middle East politics at Durham University, also predicts that for students from North America in particular, the diplomatic crisis will only reinforce the Gulf region’s reputation as unstable.

“The risk to institutions in Qatar is really that international students will stop travelling to the state to study,” he says. “Imagine the parents of an 18-year-old in America: they will be thinking carefully about whether Qatar is the right place to send their children…given other options.”

However, Al-Kuwari says that the “early indications” from the latest round of applications to study at Education City suggest that interest from outside the blockading countries had held up: “in fact, in some programmes there has been an increase in applications,” he adds.

He also claims that institutions in Education City have been watching other “dynamics” affecting applications around the world, including the downturn in international demand for places at US universities following the election of Donald Trump. “Education City has proven to be attractive to those students who have wanted to get the same kind of education [as they could receive in the US] but have wanted to stay closer to where they’re from…That is something we’re trying to capitalise on,” he says.

He adds that the crisis has also forced the foundation “to go out there and tell our story” to those who may be wary of studying in Qatar, to illustrate such factors as the diversity of the country’s student population – which Al-Kuwari says contains dozens of nationalities, with 54 per cent of those studying at Education City from outside the country.

For Davidson, the Education City model is, “when you think about it, a really clever way of levering enormous international influence” for Qatar. However, the flip side, he adds, is that other institutions, such as Qatar University – which has a higher proportion of local students – may not have had such a large slice of the investment pie. This must be “frustrating” for their academics.

Lashuel says that there have been “consistent and concerted efforts” by the Qatar Foundation and the country’s leadership, “at the highest level, to promote cross-institutional collaborations among all the institutions in Qatar”. A new Qatar National Research Strategy and rewards system for academics are also “more focused on building synergy and collaborations” within the country. “In this regard, I am very optimistic about the future of cross-institutional collaborations in the country. This is the only way they can do science at the frontier and be competitive, and I think that everyone understands this today,” Lashuel says.

Al-Kuwari also believes that Qatar University and Education City have become “part of a joint ecosystem, with “huge benefits for everyone involved: Education City benefits from Qatar University’s scale...and QU benefits from having…all that knowledge [and links] to the international world”.

The Qatari model is certainly one that seems to have been emulated elsewhere in the region, and even further afield. In neighbouring UAE, for instance, Dubai is host to branch campuses from a number of overseas universities from the UK, US, Australia and India, while New York University has a campus in Abu Dhabi. However, Al-Kuwari maintains that the Qatari model is unique because of its scale on one site and the “organic” way that it has grown.

Saudi Arabia’s approach to internationalisation has so far focused on building up the international links of existing or new universities, such as KAUST. According to Davidson, the kingdom has had the disadvantage of being a less attractive destination for academics and students than the less culturally restrictive and insular Qatar or the UAE. However, all this may be changed by the country’s crown prince, Mohammad bin Salman, who has been behind liberalising moves in the country, such as ending the internationally infamous ban on women driving, and has established a Saudi Vision 2030 aimed at reducing the country’s dependence on oil and developing its public services – which may well require greater international collaboration.

English language ability is also increasing in the kingdom: “There is definitely a new crop of Saudi youth who…have got English skills although [the country is still] about 10 years behind places like the UAE,” in Davidson’s estimation. And setting up a branch campus in Saudi Arabia would still be a much bigger risk for a Western institution, he adds – particularly as Qatari levels of funding would not necessarily be on offer from the hosts.

One thing seems crystal clear, however. Internationalisation drives in the Middle East will continue to look beyond the region, rather than within it. This is because, however great a grassroots desire there may be to collaborate with neighbouring countries, that impulse is thwarted by Arab countries’ political tensions and competing future visions, which often revolve around collaborating with more elite researchers and institutions further west.

“National competition continues to trump scientific collaboration,” concludes Kamrava. “With political tensions and mistrust pervasive [even] under normal circumstances, there is a reluctance to share information and scientific know-how, to have visiting fellowships or temporary appointments from the other countries, or to see research as a valuable academic endeavour that [should not be] dictated by political agendas and objectives.

“Within the Arab world, and within the larger Middle East, research collaboration has a long way to go.”

|

Rank in Arab World 2018 |

Rank in Arab World 2017 |

Name |

Country/region |

WUR 2018 |

Teaching score |

Research score |

Citation score |

Industry score |

International |

Overall score |

|

1 |

1 |

Saudi Arabia |

201–250 |

25.6 |

15.3 |

97.3 |

77.8 |

92.0 |

48.3–51.6 |

|

|

2 |

NR |

United Arab Emirates |

301–350 |

23.4 |

18.7 |

71.4 |

84.5 |

97.9 |

42.4–45.1 |

|

|

3 |

5 |

Qatar |

401–500 |

19.8 |

18.3 |

60.7 |

46.1 |

99.8 |

35.0–39.9 |

|

|

4 |

8 |

Jordan |

401–500 |

14.8 |

7.0 |

79.4 |

34.3 |

64.1 |

35.0–39.9 |

|

|

5 |

6 |

United Arab Emirates |

501–600 |

22.9 |

16.9 |

49.1 |

38.4 |

95.1 |

30.7–34.9 |

|

|

6 |

7 |

Lebanon |

501–600 |

25.7 |

12.2 |

52.9 |

38.3 |

87.5 |

30.7–34.9 |

|

|

7 |

9 |

Saudi Arabia |

501–600 |

16.1 |

27.3 |

39.3 |

54.3 |

97.4 |

30.7–34.9 |

|

|

8 |

3 |

Saudi Arabia |

501–600 |

24.5 |

27.6 |

30.7 |

95.1 |

78.8 |

30.7–34.9 |

|

|

9 |

2 |

Saudi Arabia |

501–600 |

26.8 |

12.8 |

37.4 |

61.7 |

85.5 |

30.7–34.9 |

|

|

10 |

NR |

Egypt |

601–800 |

18.4 |

6.4 |

63.2 |

31.8 |

43.3 |

21.5–30.6 |

|

|

11 |

13 |

Egypt |

601–800 |

23.3 |

18.0 |

24.7 |

32.5 |

68.3 |

21.5–30.6 |

|

|

12 |

14 |

United Arab Emirates |

601–800 |

15.5 |

12.5 |

22.7 |

35.4 |

96.2 |

21.5–30.6 |

|

|

13 |

10 |

Kuwait |

601–800 |

19.1 |

8.8 |

27.1 |

35.3 |

70.8 |

21.5–30.6 |

|

|

14 |

NR |

United Arab Emirates |

801–1,000 |

18.1 |

8.9 |

16.5 |

36.3 |

99.3 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

15 |

12 |

Oman |

801–1,000 |

22.2 |

10.0 |

15.7 |

47.9 |

71.4 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

16 |

11 |

Egypt |

801–1,000 |

18.2 |

7.0 |

31.9 |

0.5 |

45.4 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

17 |

18 |

Egypt |

801–1,000 |

21.5 |

11.4 |

22.6 |

33.0 |

32.9 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

18 |

22 |

Egypt |

801–1,000 |

17.4 |

6.5 |

29.3 |

40.0 |

36.2 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

19 |

17 |

University of Marrakech Cadi Ayyad |

Morocco |

801–1,000 |

18.1 |

7.2 |

25.0 |

34.1 |

41.6 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

20 |

21 |

Morocco |

801–1,000 |

24.4 |

7.9 |

20.0 |

37.8 |

30.0 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

21 |

16 |

Egypt |

801–1,000 |

16.8 |

7.9 |

23.9 |

33.4 |

44.5 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

22 |

19 |

University of Jordan |

Jordan |

801–1,000 |

19.3 |

9.1 |

11.5 |

34.8 |

62.8 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

23 |

25 |

Egypt |

801–1,000 |

21.1 |

8.2 |

13.5 |

33.0 |

34.9 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

24 |

20 |

South Valley University |

Egypt |

801–1,000 |

14.7 |

6.5 |

18.7 |

31.7 |

44.5 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

25 |

24 |

University of Tlemcen |

Algeria |

801–1,000 |

27.9 |

8.0 |

4.8 |

31.9 |

40.0 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

26 |

NR |

Egypt |

801–1,000 |

20.0 |

6.8 |

15.2 |

1.1 |

43.9 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

27 |

NR |

Saudi Arabia |

801–1,000 |

20.7 |

6.3 |

5.3 |

32.3 |

70.8 |

15.6–21.4 |

|

|

28 |

26 |

Tunisia |

1,001+ |

22.7 |

9.3 |

7.3 |

32.1 |

38.3 |

9.2–15.5 |

|

|

29 |

28 |

Morocco |

1,001+ |

25.6 |

6.3 |

9.7 |

31.8 |

22.0 |

9.2–15.5 |

|

|

30 |

27 |

Tunisia |

1,001+ |

17.5 |

7.3 |

9.6 |

31.7 |

40.9 |

9.2–15.5 |

|

|

31 |

23 |

Hashemite University |

Jordan |

1,001+ |

11.1 |

7.9 |

9.7 |

31.7 |

46.1 |

9.2–15.5 |

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?