Higher education enrolment rates across the world have soared in recent years, but there is little evidence of celebration.

In the UK, September’s news that nearly 50 per cent of English under-30s are now entering higher education for the first time in the £9,000 fee era was quickly overshadowed by figures obtained by the MP David Lammy revealing that 13 University of Oxford colleges made no offers at all to black students between 2010 and 2015. Days earlier, the sector’s higher education watchdog, the Office for Fair Access (Offa), had called for universities to make “fundamental changes” in pursuit of the “further, faster progress we badly need to see”.

Good news stories on improved social diversity in higher education also struggle to register: 20 per cent of UK 18-year-olds from the poorest backgrounds went to university this autumn, up from 11 per cent in 2006, the latest Ucas figures show. However, things are still not moving fast enough for the influential educational charity the Sutton Trust, which recently called for “radical change” in the use of contextual admissions at the UK’s top universities.

A sense of satisfaction about improving access is also palpably missing in other countries. In the US, almost half of 18- and 19-year-olds (49 per cent) entered higher education in 2015, but falling enrolments at community colleges – for decades, the engines powering US university outreach – and disquiet about the failings of for-profit institutions have stoked much debate.

And, in Australia, the removal of the cap on undergraduate numbers, completed in 2012, helped to spark a 50 per cent rise in the number of students from disadvantaged backgrounds between 2008 and 2015, reaching 146,000 entrants out of a total of 1.4 million. However, in the country’s oldest and most prestigious universities, the Group of Eight, their share of places has barely shifted since 2009, according to a report published in April by the Innovative Research Universities group. And increasing concerns about the cost of the demand-driven system could see some of the progress unravel – particularly if the government reacts to its repeated failure to get university cuts through parliament with measures that don’t require legislation. These could include re-imposing caps on funded places, cutting the Higher Education Participation and Partnerships Program (HEPPP), aimed at supporting students from deprived backgrounds, or freezing the Commonwealth Grant Scheme funding that subsidises a wide range of tuition costs.

So why has it been so hard to sell the seeming success story of wider access to university? What level of access would count as “mission accomplished”? And how could it best be achieved?

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, recently triggered debate by arguing that the UK should set a 70 per cent participation target. Hillman’s stance is not a complete surprise: he was special adviser to former universities minister David Willetts when it was announced, in 2013, that the UK would follow the Australian lead and abolish its own undergraduate numbers cap. Nevertheless, his call came at a time when some on the political Right were questioning the value for money of higher education – particularly at the lower-tariff institutions where students from poorer backgrounds tend to cluster – and suggesting that current participation levels are already too high.

Hillman, however, is unrepentant. “Every single big wave of educational expansion has been met with this response,” he says. “When the school leaving age rose to 16 in the 1960s or when Kenneth Baker, Margaret Thatcher’s education secretary, said that 30 per cent of young people should go to university, people had the same response. But South Korea has a higher education participation rate of about 85 per cent and aspiration in the UK is also running very high.”

The introduction of £9,000 fees in England in 2012 was accompanied by a requirement that universities spend a significant proportion of their additional fee income above the basic level of about £6,000 for full-time students on widening participation. Policed via the access agreements brokered by Offa, this will see them spend £833.5 million on widening participation in 2017-18 alone: just under a quarter of all income above the basic fee. But, according to Hillman, this money is not always well spent. And he notes that in the current political climate – in which the government has announced that it will freeze fees at £9,250 and launch a “major review” of higher education funding – “there will probably be less money for teaching, and, thus, widening participation, so it will be more important to spend it wisely.”

Offa’s outgoing director, Les Ebdon, believes that Hillman’s 70 per cent target is “in the right area” – particularly as it will potentially be harder for UK employers to import key skilled workers after Brexit. “Does that mean everyone will be on a traditional three-year degree course at 18? No – some want to earn as they learn and some will be more predisposed to a job but enter higher education later,” he adds.

But reaching 70 per cent would require a remarkable improvement, Ebdon notes, particularly by many higher-tariff institutions. Seven Russell Group institutions, including the universities of Cambridge and Oxford, are actually admitting fewer disadvantaged students proportionally than they were a decade ago, according to Higher Education Statistics Agency data published last year. Ebdon also notes that David Cameron’s target, set in 2015, to double the proportion of students from disadvantaged backgrounds admitted to university by 2020, from 13.6 per cent in 2009 to 28 per cent, is unlikely to be met.

Asked how he would grade the sector’s performance over his six years leading Offa, the former chemistry professor tells Times Higher Education that he would award a B for the picking of “low-hanging fruit”, such as persuading high-achieving students from poorer backgrounds to apply for elite universities and removing bias from the applications process. But he gives a D for efforts on all other aspects of admissions, and a “fail” for efforts to address “long-term inequalities” by measures such as improving disadvantaged students’ school attainment and adjusting admissions policies to reflect the challenges they face.

Ebdon’s successor, Chris Millward – who will become director for fair access at the Office for Students when it subsumes Offa next year – will have more powers and resources to push this agenda around admissions, says Ebdon.

Ebdon says that elite universities “try to absolve themselves of any responsibility” for raising the school attainment of children from disadvantaged backgrounds even while they insist on high scores and fail to use contextual data “in a consistent way”. The Russell Group’s 20 English members will spend £254 million on widening participation this academic year, but Ebdon is critical of the common tactic of offering bursaries to low-income students, saying there is only limited evidence to suggest that it influences where they choose to study. Other critics have questioned the efficacy of universities’ tendency to make one-off school visits, in an attempt to make up for the loss of information and guidance services for sixth-formers, such as the national outreach network Aim Higher, which was closed in 2011. They suggest that outreach spending should be targeted more effectively at those with the potential to succeed at university.

“We could reach 5,000 students in schools in a day, but our level of impact would be fairly low,” agrees Sarah Chick, director of education at outreach charity Villiers Park Educational Trust, which provides intensive support for high-ability students from low-income backgrounds.

The charity, which focuses on English geographical areas not served by a local university, such as Peterborough, Bedford and Hastings, works with seven cohorts of about 120 students each, selected at age 14 by their schools. It offers a programme of subject masterclasses, application advice, mentoring from previous graduates of the scheme and academic-run residential weekends at its headquarters outside Cambridge. These help to “inspire scholars to a higher level” and improve A-level grades, and also ensure that its participants leave for university “really fired up”, Chick says. “We want students to thrive at university, not just survive – they will not go on to get the really top jobs if they have [merely] passed their degree,” she adds.

For many students in lower-achieving schools, the experience of mixing with other similarly enthusiastic pupils away from their normal classrooms – often for the first time – will push them to work harder and give them a taste of university life, she says. “It is sometimes not seen as acceptable to be really enthusiastic about a subject, but this is what admissions tutors want, so we want to fire that enthusiasm,” Chick adds.

Because Villiers Park operates in areas with relatively little other outreach activity, it can work intensively with both students and schools, tracking impact systematically, says chief executive Richard Gould. Last year, for instance, 82 per cent of its scholars in Hastings, Bexhill and Swindon went to university, with 60 per cent entering “leading” universities.

“I think we’ve seen some movement away from volume and throughput [in outreach schemes nationally],” says Gould. However, he believes that a more radical shift would dramatically improve how universities’ widening access budgets are spent – which, in 2017-18, include £171 million specifically for outreach alone.

“I think the money is in the wrong hands,” he says. “It should be in the hands of schools, who would be required to spend it on access and link it to very tight targets on student destinations. [They] could commission universities to do much of the work. If every university had a [programme like ours], we would see a much greater impact compared to our current system.”

Ebdon, however, disagrees on this point. “There are all kinds of advantages and disadvantages to whether universities use their own money, but the chief advantage is that they have a vested interest in seeing it spent successfully,” he says.

Under the pre-2012 system, in which most access funding was awarded directly via government funding bodies, “the biggest aim of universities was to spend their money: otherwise you would have to give it back. Spending money on outreach shouldn’t be seen as the price that universities must pay to stay in business: they need to spend it wisely and then evaluate whether things are working.”

Another big question is how universities should identify school pupils who might benefit from engagement. Some observers are starting to ask whether the obvious and most widely used method, liaising with schools in low-income areas, is genuinely the most effective.

“The current widening participation strategy focuses on schools, but it only reaches about 60 per cent of pupils by doing so,” explains John Denham, who was the UK’s universities minister between 2007 and 2009 and is now co-director of the Southern Policy Centre, a cross-party thinktank focused on issues facing the South of England. In October, the centre teamed up with Southampton Solent University and the Higher Education Funding Council for England to publish a report, Localised Widening Participation Strategies: a Data-Based Approach, examining why some neighbourhoods have much higher levels of university participation than others with similar profiles in terms of poverty, race and educational attainment.

Denham says that these “extraordinary differences” must be addressed. In the Paulsgrove ward of Portsmouth, for instance, raising the participation rate to that of a similarly deprived ward would see an extra 20 young people attend university, he explains. “When you consider what this would mean for 20 young people and their families in this area, it brings home just how important this work is,” says Denham. He fears that the widening participation agenda is ill-served by the blur of statistics and bar charts that often represent life-changing educational experiences, and he urges universities to work more closely with other community groups, such as large local employers and social housing providers, to reach students who do not happen to attend schools served by an outreach scheme.

This issue has been partially alleviated by the launch in 2017-18 of the National Collaborative Outreach Programme, a £60 million Hefce-run scheme in which universities lead consortia of colleges, charities and other organisations to target low areas of participation not covered by current outreach initiatives. However, even this approach may still miss the many thousands of children from low-income families who attend relatively high-performing schools in their area, says Denham.

“There are some clear signs that [poorer] children are doing worse [in getting to university] than those of a similar ability [and socio-economic profile] if they go to a good school,” he says. Without direction and support, he adds, it is easy for children to “get lost” in the university application process: “That’s why we need to engage with all schools in an area: not just the one school where we think that there are more children who need help.”

Using big data to locate these pockets of underperformance will be vital as the UK seeks to push past the 50 per cent target set by the Labour government in which Denham served, he says.

“A huge amount has been achieved with a relatively broad-brush approach and the big picture is looking pretty good, but it is these micro-pockets of students that should be addressed,” he says.

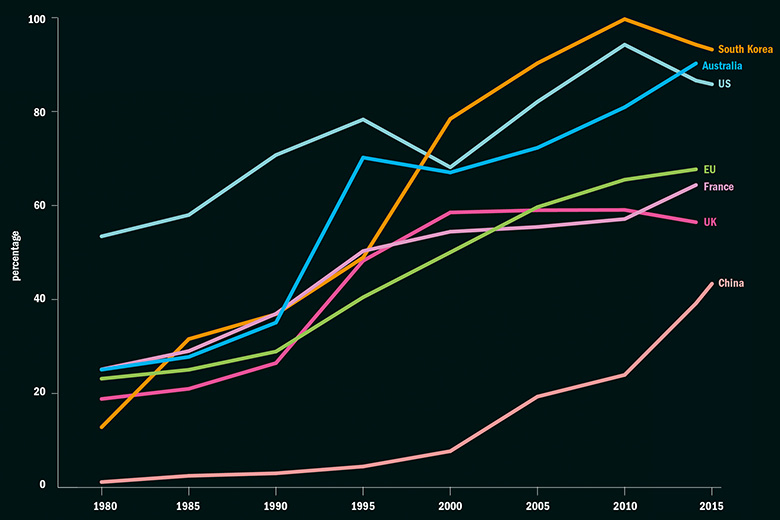

Steady growth: Tertiary enrolment rates around the world

Source: World Bank

Australia’s rapid rise in university attendance rates may be thought to provide a useful case study.

According to Andrew Norton, higher education programme director at the Grattan Institute, a Melbourne-based thinktank, part of the boom is accounted for by students from Asian immigrant communities: a “not very surprising consequence of running a migration programme heavily based on skills and attracting large numbers of people from cultures that place a high value on education”.

Conor King, executive director of the Innovative Research Universities (IRU) network of comprehensive Australian universities, broadly agrees: “Australia is reaching the 40 per cent higher education [participation] target set by the previous Labor Government through the mix of continued migration targeting skilled people and the early impact of demand-driven funding,” he says.

Data from Australia’s 2016 census show that 41.3 per cent of 19-year-olds were enrolled in higher education, and a further 11 per cent were studying for diplomas or upper-level vocational certificates. But an IRU analysis, published in April, shows that most of the heavy lifting on increasing numbers of poorer students has occurred outside the Group of Eight. Those elite universities admitted just 2,200 more students from the bottom socioeconomic quartile in 2015 – 18,000 in total – compared with 2010. Given the overall rise in student numbers, this meant that the proportion of such students at Go8 universities remained virtually unchanged, at about 10 per cent. By contrast, the six universities in the Regional Universities Network added another 5,895, while the six IRU members added 5,759. In other words, according to King, the Australian government’s plans to “focus on highly selective entry, notionally targeting the best and brightest, even with financial supports for living costs, has made little difference”.

University attendance rates in Australia’s remote and rural regions are less than half those found in inner cities. Just 18.3 per cent of 25- to 34-year-olds in these areas held an undergraduate degree in 2015, according to census data, compared with 42.4 per cent in urban areas. RUN members have done their best to improve these statistics, using HEPPP funds to cover the cost of staff travelling hundreds of miles to visit remote communities and also to bring students from such areas to university campuses. For instance, Southern Cross University in northern New South Wales worked with more than 7,000 students from 27 local primary schools and 21 high schools in 2016, organising about 100 on-campus events and in-school workshops. Meanwhile, of the 105 Year 11 and 12 students who commenced its Head-Start course that year, enabling them to take an undergraduate module alongside their high school diploma, 62 received a university offer.

Meanwhile, the University of the Sunshine Coast (USC), north of Brisbane, has created a similar scheme to demystify the idea of university. On average, there is a 42 per cent conversion rate of these students into USC undergraduates, and an additional 18 per cent said that they intended to go on to higher education elsewhere.

The apparent demise of proposed legislation that would have imposed 5 per cent cuts on university funding and raised tuition fees by 7.5 per cent is likely to be good news for many universities. However, if the government did react by cutting HEPPP funding – worth about A$2 million (£1.1 million) a year for each RUN university – such costly but effective outreach activity would have to be wound back. The organisation’s executive director, Caroline Perkins, said freezing Commonwealth Grant Scheme funding would also have “a disproportionately greater effect on regional universities” because these “rely on the government for around 40 per cent of our funding, compared to less than 20 per cent for the Go8”.

Despite RUN’s best efforts, participation of students from remote areas has actually deteriorated since 2009, according to Gavin Moodie, adjunct professor of education at RMIT University in Melbourne – “probably because government support for students’ living expenses is so meagre and mean. Australian government policy assumes that students commute from home and that those who are so poor that they qualify for a maintenance grant can supplement it with part-time work. Students from remote areas cannot meet either condition,” he explains.

Students from Aboriginal and other indigenous Australian groups should also be specifically encouraged, in recognition of their under-representation, adds Moodie. “Support for Indigenous Australians was rather better before 2009, and participation rates were correspondingly better,” he says, explaining that non-indigenous Australians objected to Aboriginals being eligible for more favourable grants than they were.

In the US, too, there are worries about the relatively low numbers of students from poorer backgrounds entering elite institutions. While US participation rates remain very healthy by global standards, some educators have worried that not all graduates enjoy the significant boost in life chances traditionally associated with higher education. One of those is Nicholas Dirks, who stood down as chancellor at the University of California, Berkeley in June 2017. His concern focuses on for-profit and online courses because these do not always count towards a degree at the kind of “flagship universities” that resonate with employers: a pathway used by more than 24,000 students transferring mostly from local community colleges into the University of California this autumn.

Dirks is proud of the fact that 40 per cent of Berkeley’s students do not pay any fees at all.

That is far from the case, however, at other top US universities, whose scholarships and fee waivers are doing little to attract bright graduates from poorer backgrounds. Peter Agre, director of the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute, believes that nearly all top US universities have an “economic diversity problem”.

“I was speaking to a class of students recently and I asked them to raise their hands if their parents were lawyers, university professors, doctors or company managers. Every hand went up,” recalls Agre, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2003. “None of these students’ parents were even school-teachers – a very important and respected job – which I’m sure was the case when I was at university.”

Sir Nigel Thrift, the former vice-chancellor of the University of Warwick, notes that “universities want to be [both] elite and inclusive, but these two things do not always add up”. Thrift, who was more recently based in New York as director of Schwarzman Scholars, a scholarship programme aimed at enabling future leaders to study for a year at Tsinghua University, recently observed in Times Higher Education that a new “middle-class activism” has emerged in the West, whereby anxious parents invest heavily in their children’s education to ensure that they can access a place at a top university. With middle-class students holding “fantastic qualifications”, it is difficult to find more room for equally talented students from more disadvantaged groups, Thrift tells THE: “The best thing is to expand the pie so that [elite] universities can include [more] people.”

But while several UK Russell Group universities have recently expanded their intakes, Oxbridge and the Ivy League have largely kept numbers the same. Just 14,483 freshmen were expected to enrol overall in the eight Ivy League institutions this autumn, compared with 13,625 a decade ago – minuscule numbers for a US higher education sector of about 20 million students. Oxford’s undergraduate intake of 3,300 in 2016 was roughly the same as Cornell’s – the largest Ivy League university intake – but it is virtually unchanged since 2006, when it admitted 3,250 students, according to Ucas figures. Cambridge took 3,435 in 2016 – just 105 more undergraduates than 10 years earlier, with the reported £18,000-a-year cost of educating students making expansion unlikely while annual fees remain about £9,000.

But, in the US, the widening participation debate tends to focus on race and, on that indicator, some US universities have made great progress. In August, Harvard University hit the headlines when it was revealed that, for the first time, the majority – 50.8 per cent – of its incoming class would be non-white. Several other Ivy League institutions – Columbia, Cornell and Princeton universities – have already achieved this milestone, while others are on course to do so soon, according to a recent New York Times analysis.

However, the newspaper also reported that the share of black students at leading US universities is virtually unchanged since 1980. While African Americans will make up 14.6 per cent of Harvard’s enrolment this year, they still constitute only 6 per cent of freshmen nationwide, despite making up 15 per cent of college-age Americans. And Hispanics are faring little better, accounting for 22 per cent of college-age Americans but just 13 per cent of students: a wider margin than in 1980.

Those disparities come despite decades of affirmative action, which has allowed universities to use race in the admissions process. The legality of this measure has been repeatedly challenged – including by Asian American lobby groups – on the grounds that it causes high-achieving students to lose out unfairly to less well-qualified candidates. The issue was seemingly settled last year when the US Supreme Court ruled four to three in favour of the University of Texas at Austin, although some fear that the Trump administration could seek to revisit the issue following the recent election of the conservative Neil Gorsuch to the court.

But some liberal educators believe that the end of affirmative action would not be a disaster. In Dirks’ view, California’s decision in 1996 to outlaw it led to a “greater focus on class and income background, rather than race” in admissions – although there are growing calls for a repeal of the ban.

Speaking at Times Higher Education’s World Academic Summit in London in September, former UK minister Willetts also raised the question of whether the potential end of affirmative action could make “America finally confront social class and use that as a backdrop for university recruitment”.

Any consideration of progress on widening participation and access is further complicated by issues such as access to postgraduate study, rising student debt levels, dropout rates and success in the labour market. Two researchers from the London School of Economics recently argued, for instance, that even Oxbridge does not provide a uniform leg up in the latter regard: Oxbridge graduates who attended an elite public school are still twice as likely to enter the UK’s elite professions as are Oxbridge graduates from state schools.

Meanwhile, Offa’s Ebdon recently lamented the decreasing entry rates for older age groups into English universities.

So does it even make any sense to set a numerical target for undergraduate participation? According to Norton, Australia’s 40 per cent target was based on “an over-optimistic analysis of the numbers of jobs for graduates”, while the 2016 census showed “that nearly 30 per cent of bachelor’s-degree graduates are in jobs that don’t typically require degrees”. His advice to the Australian government is, therefore, to privilege caution over ambition when it comes to setting new targets.

“We need to be careful to not raise expectations that have a high risk of not being met, or to encourage people to take on student debt that has a high risk of not delivering a financial return,” he says. Addressing “deep problems” with poorer children’s attainment levels at school, Norton thinks, should be a higher priority, particularly given its link to high university dropout rates.

“We should always try to act in the best interests of students and prospective students, rather than working from targets that may not reflect those interests,” he says.

But, for Hillman, stretching targets make sense given that expansion is the direction of travel internationally. However, he cautions that they must be implemented alongside efforts to effectively support university students.

“By setting a target, we can plan towards it – we can think about how we support first-generation students who don’t know what to expect [at university] and require much more help,” he says.

“I think we’re moving in the direction of 70 per cent, but if we get there by accident we won’t have prepared and will not be ready to meet the challenges of supporting students.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Chasing the elusive catch

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?