Higher calling: NCEE runs the annual Entrepreneurial Leaders programme, which has had more than 150 senior university leaders take part

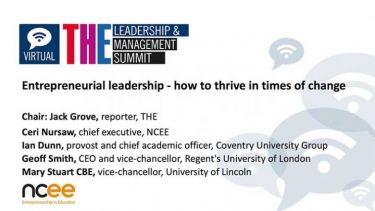

More than ever, university leaders need to be managers of change, says Ceri Nursaw, chief executive of the National Centre for Entrepreneurship in Education. “Nothing remains still. The speed of change is increasing, not to mention the pressure from external factors such as Brexit,” she explains. To stay ahead of this curve, they need to embrace the principles of entrepreneurship – and that goes way beyond supporting students to succeed in the world of business. With this in mind, Anglia Ruskin University, the University of Central Lancashire, and the universities of Salford, Lincoln and Coventry have teamed up with the NCEE to embed and develop entrepreneurship in higher education in the UK and internationally.

Ian Dunn, NCEE chair and deputy vice-chancellor of Coventry University, argues that entrepreneurship is not something that can necessarily be “taught” but is rather in an institution’s DNA. “It should be visible in the business model and behaviours, how you approach research and knowledge exchange,” he says.

Coventry has a long-standing partnership with Unipart Manufacturing, for example, which is renowned for being the UK’s first “faculty on the factory floor”. The institution has also built a network of university colleges where tuition fees are set at a lower level to enable more disadvantaged students to access a high-quality education.

Taking decisions to do things differently incorporates an element of risk that entrepreneurial leaders need to be comfortable with. “We’re dynamic and take an opportunity if we see it,” says Professor Mary Stuart, vice-chancellor of the University of Lincoln. Its business incubation centre, Sparkhouse, has supported the growth of more than 300 start-ups and the university is estimated to be worth in excess of £300 million to its local economy. “I’d describe our approach as risk aware – we go into things with our eyes open,” she says.

Enterprise is rooted in Lincoln’s traditional courses, too. For example, students on its conservation degree work on paid projects for a spin-out consultancy, and the Siemens gas turbine worldwide training facility is co-located in the engineering school.

When it comes to recruitment, Stuart seeks people who embrace change: “It takes a certain type of person to work here – someone forward thinking and happy to adapt. We can turn a course around in four weeks if there’s demand for it,” she says.

Meanwhile, Professor Iain Martin, vice-chancellor of Anglia Ruskin University, says the universities that will thrive over the next few years are “those that look for innovative ideas to implement and an entrepreneurial skills culture that can turn those ideas into reality”. The Anglia Ruskin Enterprise Academy runs an annual “Little Pitch” competition, where students are invited to come up with a business idea via a tweet or text message – an idea that has since been picked up by the Virgin Group.

“Entrepreneurship is so important, whether you’re a student of business or of creative arts, so while we do run formal initiatives, a lot of it is simply embedded in how we do things,” Martin adds.

Creating the right environment for entrepreneurship to flourish is crucial. The University of Salford has created Industry Collaboration Zones that focus on industry partnerships in four areas – engineering and environments, health and society, sport, and digital and creative. “I want staff and students alike to take risks,” says the vice-chancellor, Helen Marshall. “My job is to make sure that the institutional framework is there for them to be able to do that.”

Salford is also collaborating with the NCEE to take entrepreneurship in higher education to a more global audience, working with six universities through the British Council in Palestine to embed an entrepreneurial curriculum and culture.

Learning from others by taking part in development activities such as the NCEE’s Entrepreneurial Leaders programme can help senior university staff develop their institutions’ entrepreneurial capacity. Dunn argues that an entrepreneurial leader is “able to connect with others; someone who is a complex problem solver, who can see things in both breadth and depth”.

But while the Higher Education Funding Council for England estimates that student start-ups and spin-outs have a gross annual value of around £2.7 billion, being an entrepreneurial institution is not only about how many businesses are created or patents filed. For Professor Mike Thomas, vice-chancellor of UCLan, community is a core part of the entrepreneurial agenda. “Part of being an entrepreneurial university is engaging with people who have different ways of thinking and bringing in people from outside so they get to know more about what their university does,” he says.

The Entrepreneurial Leaders programme is aimed at senior university staff keen to embed entrepreneurial thinking in their institution. For details, go to ncee.org.uk