A second high-profile congressional hearing appears to have done little to settle the free speech confusion across US higher education, with a new round of student protests and arrests punctuating expert assessments that many campus administrators and government policymakers lack the necessary understanding and insight.

The hearing this week – featuring Columbia University’s president – followed a similar Capitol Hill session in December that led to the ousting of the leaders of Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania.

The Columbia president, Baroness Shafik, perhaps seeking to avoid a similar fate, followed her testimony in Washington with an immediate crackdown on a pro-Palestinian demonstration taking place at her New York campus, featuring the arrests and academic suspensions of more than 100 students.

“This is a challenging moment and these are steps that I deeply regret having to take,” the Columbia president said in announcing her decision to request a New York police response. “I encourage us all to show compassion and remember the values of empathy and respect that draw us together as a Columbia community.”

Her response contrasted with those of the since-departed leaders of Harvard and Penn, who kept trying to reason with Republican lawmakers and wealthy donors who were demanding that US universities harshly punish any students challenging the conservative leadership of Israel over its military assaults against Palestinian civilians.

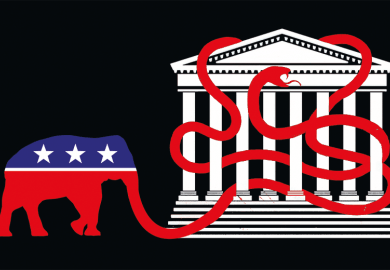

The two hearings were held by the education committee of the US House of Representatives, whose Republican members regularly challenge principles of academic freedom and portray opposition to Israeli government policies in Gaza as tantamount to “supporting terrorism and violence against the Jewish people”.

The panel’s chair, Republican Virginia Foxx, opened the hearing with the Columbia president by complaining that her Ivy League university was among several top-ranked US institutions that “have erupted into hotbeds of antisemitism and hate”.

After Columbia took less than 24 hours from the hearing to order the police action against its own students, Ms Foxx claimed credit, saying the university’s sudden decision “to correct course” demonstrated the “essential” value of the pressure her committee was putting on US higher education.

Columbia leaders said that the two-day encampment on their university’s main lawn “violated a long list of rules and policies” and “damaged campus property”, while Ms Foxx said it had “plunged Columbia’s campus into chaos and endangered its students”. Neither offered details of the damage.

The arrests at Columbia came at the same moment that free speech experts – including a top Biden administration official – joined a previously scheduled conference at the University of California. There, they acknowledged that while some campus free speech decisions could be difficult, institutions generally should take a two-part stance of showing tolerance for a wide range of political expressions and helping anyone who might be troubled by them.

Catherine Lhamon, the assistant secretary for civil rights at the US Department of Education, described previous attacks aimed at Jewish students at the University of Vermont, including a teaching assistant who allegedly threatened them with lower grades. After an initial reluctance to respond, the university was prodded by a federal enforcement action into working aggressively to help its Jewish students, to the point where more students are now joining Jewish groups and feeling safe showing their Jewish identity on their campus, Ms Lhamon said.

The Vermont case shows that meaningful improvement is possible “without violating core tenets like academic freedom and free expression”, she said.

The dean of law at the University of California, Berkeley, Erwin Chemerinsky, said that solutions might often not be that simple, but also promoted the idea that universities – for reasons of both law and effectiveness – should broadly avoid speech limits and meet their federal obligation to help anyone left feeling anxious.

Professor Chemerinsky had his own first-hand experience with heated campus tensions this month when he extended an annual invitation to his law students to have dinner at his house and was greeted by several who chose to interrupt the moment with speeches protesting Israel’s military assaults on Gaza.

Universities should establish clear times and places for protest speeches, with central public lawns a common venue, Professor Chemerinsky told the conference. And while the dinner at his private residence was not one of those opportunities, the professor noted, he had not tried to remove posters from the Berkeley campus that cartoonishly depict him as a bloodthirsty Zionist.

“I allowed the hateful fliers to remain on the bulletin board, because it’s protected speech under the First Amendment,” said Professor Chemerinsky, a co-chair of the Advisory Board of California’s National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement.

That openness was less evident at the congressional hearing, where Ms Foxx was among several lawmakers who repeatedly demanded that Columbia heavily punish faculty and students who have expressed pro-Palestinian sentiments, and the university’s president expressed a willingness to comply.

One of the committee’s Republican members, Rick Allen of Georgia, asked the Columbia president if she wanted her university “to be cursed by God”, before suggesting the university offer courses on the Bible.

Another, Burgess Owens of Utah – one of the first black athletes ever recruited to play football at the University of Miami – said after the hearing that he believed Jews suffered worse hostilities on US college campuses than those of any other demographic group, including black Americans and Muslim Americans.

It took the October attack by Palestinians in Israel for Americans to realise that fact, Mr Owens told Times Higher Education. “It’s been there – we just didn’t see it,” he said. “So it was just a matter of time before it was going to explode.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?