A new contender for a proposed national test to identify the relative strengths and potential of university applicants was unveiled this week by an international partnership of exam boards.

Universities could use the test to identify hidden potential that is not reflected in A-level results, the boards claim. It would also allow student advisers to direct young people to different fields according to their abilities.

The test represents a rival to the US-style SATs the Sutton Trust charity believes should be trialled as a national admissions test for universities.

The test is produced by the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (Ucles) and the Australian Council for Educational Research (Acer). It was presented at the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service annual admissions officers conference at Keele University this week.

The government-commissioned review of admissions headed by Steven Schwartz, vice-chancellor of Brunel University, found disagreement among admissions tutors over the extent to which the merit of an applicant was measured by achievement and potential.

But Professor Schwartz said: "It is very hard to develop a test of potential that is uncontaminated by things such as parental income. But if they can do it, there would be a tremendous market for it."

The test could replace those run by elite universities for courses in biomedicine and law and the Thinking Skills Assessment, which is used by Cambridge University for many of its courses.

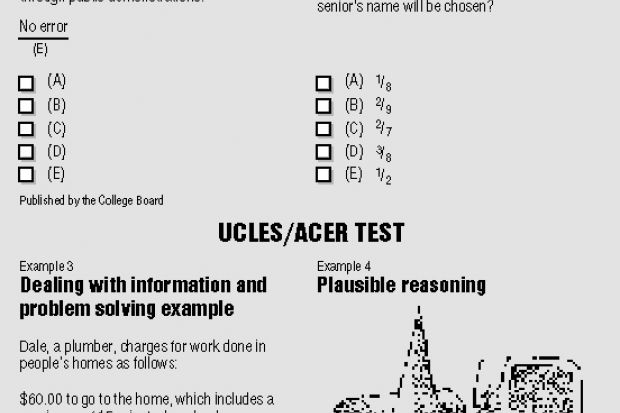

It comprises three types of question covering quantitative and formal reasoning, critical reasoning and verbal and plausible reasoning. The test consists of 96 multiple-choice questions taken over two and a half hours.

Students would receive three sets of marks, one for each component of the test. Admissions staff would then decide which components were most important for each course. For example, a maths applicant might require a higher score in the quantitative and formal reasoning section than in the verbal and plausible reasoning section, which covers reasoning used in, say, law.

The test would be taken in the September of year 13 (upper sixthform) - before the October 15 deadline for admissions to Oxford and Cambridge universities and all medical schools - or simultaneously with AS levels at the end of year 12 (lower sixthform).

Ron McLone, director-general of assessment at Ucles, said: "Responding to the Schwartz report's desire to minimise the burden of higher education admissions testing on candidates and institutions alike - but recognising the need to give institutions a reliable instrument for achieving their selection and/or widening participation objectives - Ucles and Acer have joined forces to develop a single generic test."

The Schwartz review recommended commissioning research into the idea of a national test of potential - and the Sutton Trust is lobbying the Department for Education and Skills to fund a study of 50,000 students to sit US-style SATs from this autumn.

Tessa Stone, director of the Sutton Trust, said that the US SATs had demonstrated their worth in discriminating between high-flyers and spotting hidden potential while the new test had yet to do so.

She said: "Does it make sense for British universities as global players? In a global market, it could be more sensible to have something that is taken all over the world."

The Schwartz review also recommended that any such test should sit within the current qualifications framework. But the test devised by Ucles and Acer is not intended to be part of this framework.

Manchester University will use the biomedicine admissions test developed by Ucles to identify potential in applicants to its foundation-year programmes in medicine and dentistry.

At present, the test is used to discriminate between students applying to read medicine, dentistry and veterinary science at the universities of Bristol, Cambridge and Oxford, Imperial College London, University College London and the Royal Veterinary College.

* Admissions staff will be asked to report how top-up fees affect recruitment to protect universities with strong access records, the admissions conference heard.

Sir Martin Harris, director of the Office for Fair Access, said: "We need to monitor extremely carefully what happens in 2006. We do not want to be taken by surprise."

Sir Martin told delegates that institutions with a good access record would need to respond quickly if they had too many students making too many claims for support.

alison.goddard@thes.co.uk </a>

<P align=center>

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?