Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab was arrested on Christmas Day for the attempted bombing of an aircraft on a flight to Detroit from Amsterdam. Had he succeeded in his mission, it would have been an act of terrorism causing mass murder on an appalling scale.

What induced this behaviour remains a mystery. He has not emerged from a background of deprivation and poverty. He came from one of Nigeria’s wealthiest families. He was privately educated, and to a high level. He gained admission to University College London, where he studied mechanical engineering with business finance between 2005 and 2008, and was president of the UCL student Islamic Society in 2006-07.

The events of Christmas Day came as a complete shock to the UCL community. Those who taught him have described him as a well-mannered, quietly spoken, polite and able young man. He was provided with the usual high standard of pastoral care, but his tutors observed no aberrant behavioural issues. The same picture is painted by his fellow students – here was an ordinary student.

Elements of the British press have taken a different line. Mr Abdulmutallab studied at UCL, therefore he must have been “radicalised” at UCL; after all, according to The Daily Telegraph, “[e]ven though Abdulmutallab is not even a British citizen, he was still allowed to be elected president of the Islamic Society at [UCL]”. And more: “It is easy to imagine that the authorities at UCL took quiet pride in the fact that they had a radical Nigerian Muslim running their Islamic Society. You can’t get more politically correct than that. They would therefore have had little interest in monitoring whether he was using a British university campus as a recruiting ground for al-Qaida terrorists such as himself.”

This is quite spectacular insinuation. And without so much as a shred of evidence in substantiation. The Telegraph blog that follows the publication of this piece displays quite disturbing Islamophobia, anti-immigration rants and even postings calling for the bombing of UCL itself.

Other UK newspaper comment accuses us at UCL of being “complicit” in the radicalisation of Muslim students; and, again, of “failing grotesquely” to prevent extremists from giving lectures on campus. Mr Abdulmutallab’s presidency of the UCL student Islamic Society is further condemned for having provoked debate about the war against terror. It is a delicious irony that a theme that has sold so many national newspapers should now be declared by them to be unacceptable for student debate.

The US media, on the other hand, have in general been studiously careful in reviewing facts and in ensuring that comment is underpinned by evidence.

Their example needs to be more widely observed.

What is needed is a sober and thorough assessment. We are currently providing all assistance to the authorities, and I am setting up a full independent review of Mr Abdulmutallab’s time at UCL. If any evidence emerges of a wider malign impact on him or by him, we shall certainly take appropriate action.

Where we will not yield, however, is in our commitment to the fundamental values of a university: to the equality of opportunity that was enshrined in UCL’s foundation in 1826 as the first university in England to admit students without reference to class, race or religion. We have always been a secular institution, and we will continue to admit students on academic merit alone.

Nor will we accept restrictions on freedom of speech within the law. There is no question but that we will continue to allow our students to form clubs and societies for all legitimate pursuits, and encourage the vigorous debate, disputation and criticism that is central to the very concept of a university.

We will also continue to guarantee freedom of speech on campus for visiting speakers. The example cited by the UK press of our “grotesque failure” to prevent an extremist from speaking on campus is simply untrue. It involves a recent case in which an Islamic preacher, Abu Usama, with views considered abhorrent by many, was invited to speak at the UCL Union. Once the wider issues around his views became known, the invitation was swiftly withdrawn by the students and the event did not take place. I might add, however, that had that not occurred I would have intervened because the invitation had not been issued in accordance with our Code of Practice for freedom of speech on campus, which reflects the obligations imposed upon us by the Education (No 2) Act 1986.

There is a narrow line that we must walk between securing freedom of speech on the one hand and safeguarding against its illegal exercise on the other, such as in the incitement of religious or racial hatred. There is nothing unique in this for universities. We – and our students – are subject to the law in the same way as newspapers.

The events of the past few days put all British universities on notice, not only of the need to maintain vigilance against the misuse of the liberties we protect, but also of the astonishing lack of comprehension on the part of some of our news media – and no doubt far more widely – about the unique character of universities as institutions where intellectual freedom is fundamental to our missions in education and research.

I cannot resist one final irony, not yet picked up by the press, which is that the UCL faculty of engineering sciences in which Mr Abdulmutallab studied is today a major global centre for research and training in counter-terrorism. It runs a masters degree in that subject and has pioneered new technologies for airport safety and tracking. Universities are fully in the real world.

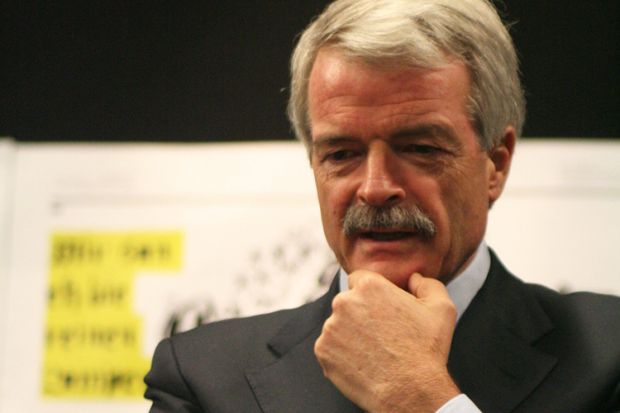

Malcolm Grant is president and provost, University College London.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?