Students at an Indian university have entered their 12th day of a hunger strike prompted by expulsions of protesters seeking an increase in financial aid.

What began last month as a general protest at South Asian University has since escalated dramatically, with two students taken to hospital in critical condition. Yet, the standoff between students and administrators shows no sign of abating.

It is not the first time the New Delhi-based university, which is sponsored by the eight member states of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, has seen clashes between students and administrators, with annual protests over fees and other issues taking place since 2015.

But students said the administration’s step to expel learners for protesting were unprecedented – and a worrying attempt to silence students’ right of expression.

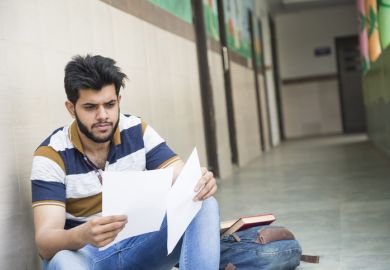

Times Higher Education spoke to Umesh Joshi, a PhD student in sociology at SAU, who was recently told he has been expelled for his participation in the actions. He had just rejoined the hunger strike by eight students.

“Everything now has shifted to the question of expulsion…it’s like strangling students and telling them if you speak up for anything…you’ll be thrown out,” he said.

Mr Joshi said students first sent grievances to their faculty advisers and deans in early October, but received no reply. Hundreds of SAU students protested, and on 13 October, administrators called the police. On 31 October, students occupied the administrative floor. Four days later, the administration announced the expulsions of two students and suspensions of three of them, prompting the hunger strike.

“We began with very simple demands,” said Mr Joshi. Chief among them, students are calling for parity in scholarship awards between local and non-local students as well as higher stipends in need-based scholarships.

Both the number of financial aid awards and the amount of money allocated has been “significantly reduced each year”, making study untenable in one of India’s most expensive cities – particularly for students from neighbouring countries, such as Nepal and Bhutan, according to Mr Joshi.

Students on need-based stipends receive 3,200 rupees (£33) per month for cafeteria costs, leaving them with 800 rupees – barely enough to cover the cost of necessary study materials – leaving nothing to attend academic conferences or for other needs, he said.

The protesters also want representation on the university complaints committee, where they currently have observer status – something administrators say is impossible because of the confidential nature of its meetings.

But the protest has since “moved beyond” initial demands, said Amol Sharia Suresh, a second-year master’s student at SAU.

“Administration is still not ready to listen…nor have they shown any concern about students’ health and lives,” he said. “We are opposing this arbitrary action [of expelling students to ensure] the existence of protest space [and] dissent in the future.”

A spokesperson for SAU defended the administration’s actions, saying it gave protesters a “point by point response to the students agreeing to most of the demands and reasoning out why some…couldn’t not be granted right away”. He said the institution was justified in calling the police to “prevent any further disturbance of the peace”.

He noted the university provides all PhD students with a stipend of 25,000 rupees per month (£258), saying it had been “very considerate about the needs of the students”, particularly during the pandemic. The spokesperson also told THE the student expulsions and suspensions were within the president’s rights and SAU bylaws.

According to media reports, officials accused students of misconduct including “manhandling” the president and making him “captive in his office” as well as “playing loud music continuously” since 1 November.

Mr Joshi acknowledged that protesters employed tactics including playing music, sitting outside the president’s office and not allowing administrators to leave until they spoke with students. He was sceptical that leadership would otherwise listen to protester demands.

While Mr Joshi was dismayed by what he called a “callous” attitude by leadership, he was nonetheless hopeful that university leaders would talk to students. In the meantime, the strike would continue, he said.

“I probably will sit here with my mattress and try to finish my thesis – if nothing works out, we’re going to court.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?