“At this moment, maybe 10 or 20 people know that you are here,” Afshin Ellian told Times Higher Education during a meeting at his office at Leiden University’s law school, one of the few locked parts of the campus and the only corridor with a dedicated security guard, who offers coffee.

Tehran-born Professor Ellian, head of the jurisprudence department and a published poet, was welcoming but watched closely when his guest reached into a bag for a notebook. “We had to change the mentality, to accept that some parts of the building have to be closed or guarded. It’s so against the culture here,” he said.

A tempering of Dutch openness is justified. In 2019, the government accused Iran of being behind the assassination of two Dutch-Iranian dissidents, one of whom was shot dead in the street minutes from the foreign ministry.

Professor Ellian was invited to come from Iran to the Netherlands in 1989 aged 22, as part of a United Nations programme for political refugees. In the years since, he has become a prominent critic of radical, political Islam, publishing a regular column in De Telegraaf, the country’s most widely read daily newspaper.

Although he enjoys a public profile, his academic work can be stymied by security. Lecturing at Leiden is safe, for example, but travelling outside an approved agenda or to countries without a bilateral security agreement is out of the question.

He received his first death threats in 2002, when he wrote a column explaining the distinction between Islam as a personal religion and a political ideology. In the decades since, he has been threatened through letters and emails, on social media and by messages passed through friends and acquaintances.

The most intense period was between 2004 and 2012, which began with the assassination of Dutch film director Theodoor van Gogh and ended with the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, when it became public knowledge that Dutch security services were monitoring communications and making arrests over threats.

Leiden has been “very supportive” about his security situation, and Professor Ellian acknowledged the “very difficult” security planning that universities and others must do for threatened academics. However, he said many rectors and presidents could be more outspoken in their support for scholars dealing with security risks.

“It would be very good, very necessary if rectors in not only the Netherlands but in Germany and the United Kingdom were more solid with people that are threatened by radical Islam, the anti-vaccination movement or the far right. Honour people and make a statement. You don’t honour the ideas of people; you honour the courage.

“That’s a very important message to the community, to the young, to other professors. The danger of tyranny and terror is the danger of self-censorship and capitulation.”

It is “very risky”, but Professor Ellian said he could give a public lecture, although he has chosen not to do so for more than a decade due to the many requests for security planning he would have to make.

“You are always a computer, a machine. If I want to speak to people, I have to plan everything,” he said. To spark the ideas that come from accidental intellectual encounters he sometimes speaks with a “faculty of the imagination. I try to create a kind of imaginary world to speak with people in my mind, to create some kind of spontaneous meeting.”

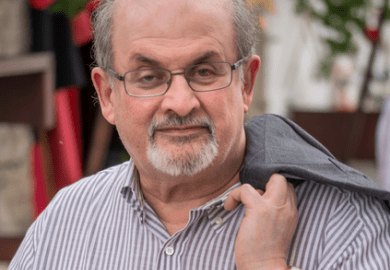

August’s attack on author Salman Rushdie in New York underlined the risks still faced by critics of political Islam. Professor Ellian, who had previously urged Mr Rushdie to remain cautious about his security through mutual friends, found out about the on-stage stabbing like many others – through a flurry of push notifications on his phone.

He said it was “very ironic” he heard the news of an attack in a relatively peaceful, liberal country while having dinner at the house of a Jewish friend, who had as a child escaped the Holocaust with the help of the Dutch resistance. Shocked into minutes of silence, he didn’t think that he “could be next” but of his cousin who was executed in Iran as a teenager. “In those long five minutes I saw his picture in my head, and many other people who were killed by the Islamists.”

Security impacts the personal lives of some threatened academics. But even after decades of strain, Professor Ellian still treasures liberal society. “You can be what you are; you can speak your heart against government or other people. That’s the paradise, that’s the heaven that Moses and Muhammad and Jesus promised us.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?