This month brought yet more insight into dismally unequal economic performance across the UK regions. According to new Office for National Statistics data, output per hour grew in six regions in 2018, including London and the south east (which were already streets ahead of the rest). But it shrank in six regions: down by 2.5 per cent in Yorkshire and the Humber, 2 per cent in Northern Ireland, 1 per cent in Wales, 0.8 per cent in the north east.

Those lagging regions are a key factor in why UK productivity is 20 per cent below where it would be if pre-financial crisis trends had continued. The productivity figures are not abstract: they mean lower wages, a smaller tax take for the government, less money to spend on public services, and more people stuck in declining towns and cities.

What the Conservative general election victory – won in Leave-voting industrial towns across the Midlands and the north – appears to have done is create a political driver to mount the kind of “levelling up” in the regions now talked about by Boris Johnson.

Dominic Cummings, the prime minister’s most senior adviser, has said that those searching for ideas on how to “really change our economy for the better, making it more productive and fairer”, should look to a paper by Richard Jones, a professor of physics at the University of Sheffield. His paper argues that research investment can be the stimulus to help “lagging regions break out of the low innovation, low skills, low productivity equilibrium that they are trapped in” and thus create a “more prosperous, equal and united country”.

As the new government pledges to double research spending, a rebalancing of research investment towards the regions is being billed as potentially transformative for the nation. And as spelled out in a recent speech by Chris Skidmore, the universities and science minister, that means changing a system in which the golden triangle – usually defined as the universities of Cambridge and Oxford plus the most prestigious London institutions – “benefit disproportionately from public [research] investment, compared with other regions of the UK”. Such shifts could, perhaps, challenge the UK’s hierarchy in research and change the outlook for many researchers.

But while there are influential figures seemingly behind the regional rebalancing agenda in research funding, there will also be powerful forces in opposition. How might the battle between the “excellence-based” funding model dominant at present and a “place-based” model shape up? And how could a rebalancing to the regions be achieved in practice?

Professor Jones’ paper pinpoints three weaknesses in the UK’s research and development base: it is “too small for the size of our economy”; it is “particularly weak in translational research and industrial R&D”; and it is “too geographically concentrated in the already prosperous parts of the country”.

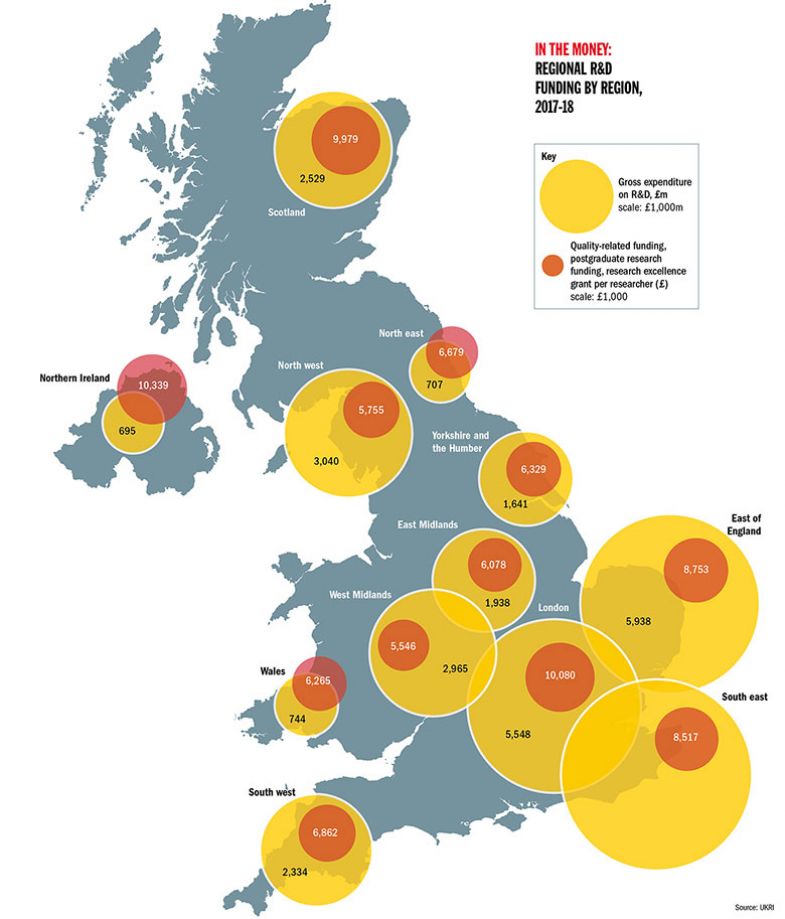

Professor Jones, a former member of the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council’s governing council, questions whether, in reality, research funding policy up to this point really has been “excellence-based”. “Just naturally, if you run a place-blind system it will concentrate resources in particular places, just because of the dynamics of the system,” he told Times Higher Education. His paper states that Oxford and its environs, Cambridge and its subregion, and inner West London “account for 31 per cent of all R&D spending in the UK”.

What is needed is “a systemic break with what’s happened in the past”, Professor Jones said.

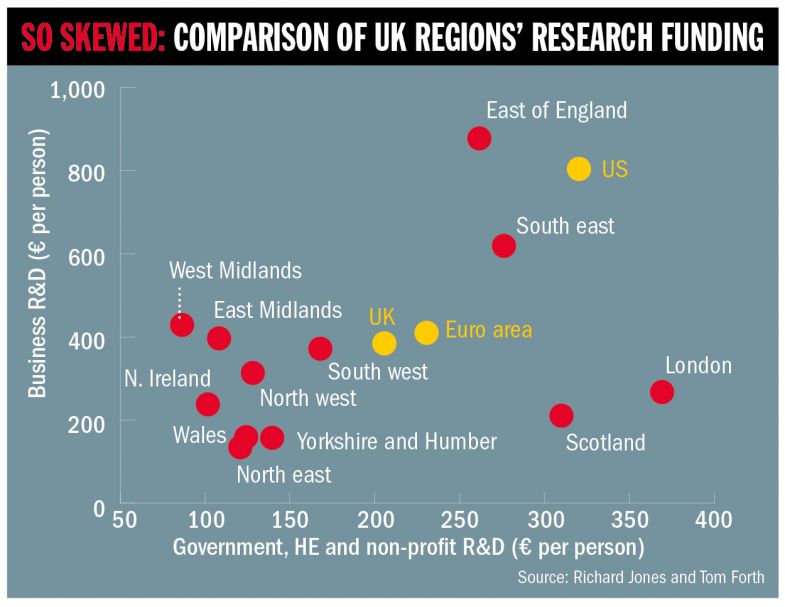

Tom Forth, head of data at Leeds-based The Data City, has worked with Professor Jones to compile figures showing how business and government investment in research goes to different regions. He said opponents of rebalancing public investment to the regions “will argue that we are moving away from excellence – I would challenge that premise”.

“The market is pretty good at assigning money…If we moved the [public] funding to be more similar to where business spends money on R&D, we would actually be more likely to be funding excellence,” said Dr Forth.

But such moves, he added, “will be very negatively received by…Oxford, London and Scotland – those are the three places that would struggle”.

There could be further scepticism elsewhere. Andy Westwood, professor of government practice at the University of Manchester, said UK Research and Innovation, the powerful strategic science agency, was “sort of on board” with the rebalancing agenda, but “culturally it has been set up on an excellence model”. Parts of government, notably the Treasury, may share objections, he added.

But the rebalancing agenda seems to have an ally in Mr Skidmore, whose recent speech pledged to “put in place a true ‘one nation’ R&D strategy”.

David Sweeney, executive chair of Research England, part of UKRI, said the organisations were working with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy to develop this plan and “will take very seriously the place strategy” that emerges.

Was it fair to say that research investment was regionally imbalanced at present? “In terms of Research England, we award funding on the basis of quality and volume,” replied Mr Sweeney. “And the reality is there is more research going on in the south than the north – that’s just a fact of where the research is located.

“And it’s also a fact that we’ve got some very, very strong universities – more strong universities – in the south than in the north. Although the universities in the north are doing well.”

But Mr Sweeney added: “We’ve indicated that we can award funding on other bases, because that’s what Strength in Places [the place-based UKRI funding scheme] and what E3 [Expanding Excellence in England] do…There are broader ways of considering need, assessing potential and assessing excellence.”

Deciding on the right mechanisms to achieve rebalancing will be another key debate. Professor Jones’ paper argues the case for using “new translational research institutions as nuclei” to build local and regional innovation systems. The Catapult Centres created by Innovate UK (now under the wing of UKRI) have been “a positive step”, but are generally not yet at sufficient scale, he says. Mr Cummings may favour independent research institutes above universities, some think.

Professor Jones highlights as a role model the University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre, part of the High Value Manufacturing Catapult, which has attracted Boeing and McLaren to open new factories at its site on the Sheffield-Rotherham boundary.

Keith Ridgway, the AMRC’s founder, explained that the centre’s original aim, in a South Yorkshire region “written off following the decline of the mining and steel industries in the late ’80s”, was to build on the area’s “incredible capability in cutting aluminium and titanium, two metals vital to the global aerospace industry”.

The AMRC helps the 100 or so manufacturers that constitute its membership (large global firms such as Boeing, Rolls-Royce and Siemens and smaller, locally based companies) to conduct R&D on advanced machining, manufacturing and materials by connecting them with university researchers. The operation also includes a training centre for engineering apprentices.

Professor Ridgway, now executive chair of the Advanced Forming Manufacturing Centre at the University of Strathclyde (also part of the HVM Catapult), said such centres needed “a more focused funding mechanism that is delivered at scale and pace”, but saw a “strong consensus that rebalancing needs to be both geographic and towards applied R&D”.

“This could be a great moment for smaller, regional universities who, while not research-intensive, have intensive research strengths that could be expanded and extended to sow the seeds of renewal and regeneration in our forgotten or neglected towns,” he said.

Professor Jones’ paper calls for investment to be focused on industrial sectors that build on existing local strengths (as the AMRC has done) “while exploiting opportunities offered by new technology”, prioritising innovation in areas including low-carbon energy, health and social care, and the manufacturing base that is still key for so many regional cities and towns.

In addition to translational research centres, Dr Forth backed the idea of giving “big pots of money to metro mayors” for R&D, as “the only devolved structure that we have” in government. West Midlands mayor Andy Street wants to create a “Gigafactory” for electric vehicle factories in the region. “If he had his own R&D budget, he could put out a call for someone to build one,” said Dr Forth.

With a major increase in research funding expected to start being fed through in the forthcoming budget and spending review, perhaps there will be scope to accommodate both excellence-based funding and place-based systems. “You can now think about doing this in a way that’s not a zero-sum game,” said Professor Jones.

john.morgan@timeshighereducation.com

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: How might UK research funding be rebalanced?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?