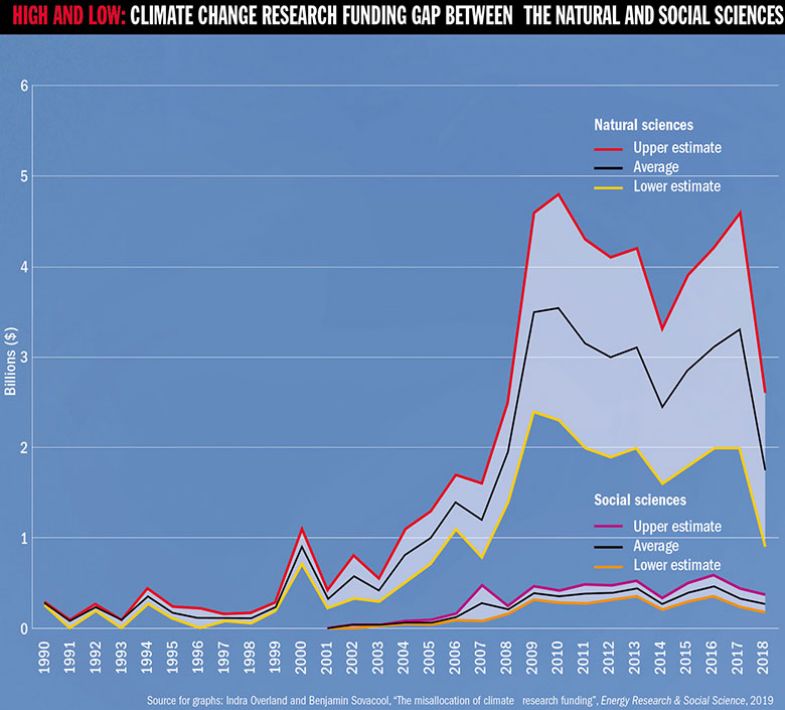

Academics who found that just 5 per cent of all climate change research funding goes to examining how the environmental crisis might be mitigated by behavioural change have warned that mankind will struggle to tackle it without greater investment in the social sciences.

Analysis by scholars from the University of Sussex and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs of funding awarded globally over the past three decades found that just $4.6 billion (£3.5 billion) was spent on climate change research in the social sciences and humanities, compared with $40 billion that went to the natural and physical sciences.

However, much of this funding went towards studies unrelated to mitigating climate change – such as how to manage extreme weather events or how historic climate change affected ancient civilisations, according to a paper published recently in the journal Energy Research & Social Science. Funding for social science-focused research into how energy use might be reduced by changing human behaviour accounted for just $393 million, 5.2 per cent of the total, the study estimates.

“The funding of climate research appears to be based on the assumption that if natural scientists work out the causes, impacts, and technological remedies of climate change, then politicians, officials, and citizens will spontaneously change their behaviour to tackle the problem. The past decades have shown that this assumption does not hold,” write Benjamin Sovacool and Indra Overland.

Professor Sovacool, professor of energy policy at Sussex, said he was shocked by the historic underfunding of social science-related funding. The massive imbalance in climate change research funding might be explained by the perception that some areas of social science study were considered to be “wishy-washy” or “caught up in obscure theoretical debates”, said Professor Sovacool. But the preference might also be explained by the desire for a “simple solution” based purely on science.

“It is comforting to think there is a simple solution to climate change and it is a wind turbine,” said Professor Sovacool, who argued that the social sciences “force us to deal in complexity”.

“Even a highly technical solution will need social science expertise to see if it resonates with people’s values,” he added.

The new study, which analysed research grants worth $1.3 trillion that were made by 332 funders globally between 1990 and 2018, found that climate-related research accounted for 4.6 per cent of the total, with the social science of climate mitigation capturing 0.12 per cent.

Social science research into climate change – such as a multinational study published in June 2019 by Professor Sovacool and others on how willing people are to reduce carbon emissions – could be vital for enacting social policies to lower greenhouse gas emissions, he said.

However, Stefan Ostlund, professor of electric power engineering at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden, questioned whether the funding imbalance was as inequitable as feared. “It is very simple to say [this imbalance] is unfair,” said Professor Ostlund, who is vice-president (global relations) at KTH.

“Unless you are going to change people’s behaviour fundamentally – and there is evidence to suggest that this is very hard to do – we need to invest heavily in research in technology, in infrastructure and in changing manufacturing if we truly want to have a fossil-free society,” said Professor Ostlund.

Most carbon emissions currently come from electricity and power generation or from road transport, where technological advances would be required to reduce emissions significantly within 20 years, argued Professor Ostlund.

“If we want electric cars, one of the major problems to address is that our power distribution system is not big enough – that will require a massive investment in R&D, but also infrastructure,” he said, adding that political or social incentives to encourage this greener form of transport were not enough on their own.

“Social science research will help to transform the political system to make this happen, but we need to continue developing new technology when it comes to transportation, power grids, solar cell and battery life,” added Professor Ostlund.

He observed that China was currently building coal-burning power stations with the capacity to create 300 gigawatts of power a year – the equivalent of 200 nuclear reactors – suggesting that technology would have to play a role in reducing this kind of power generation. “To make the enormous changes we need, there must be large and continued technological investments,” Professor Ostlund said.

Angela Liberatore, head of the unit of social sciences and humanities at the European Research Council, told Times Higher Education that the historic trends measured by the study might be changing. Some 23 per cent of the ERC’s €2.2 billion (£1.9 billion) annual funding now went to the social sciences, which had many projects focused on climate change.

“At a recent ERC conference on research into climate change, there was a social scientist on almost every panel,” said Dr Liberatore, who noted that the announcement of the European Green Deal, a commitment to make the continent climate-neutral by 2050, promised more funding for climate change research. “You can definitely expect more funding across the board, and that will include a lot for social sciences,” said Dr Liberatore.

More generally, Professor Sovacool called for an overall increase in the amount of funding allocated to climate change-related research in all disciplines.

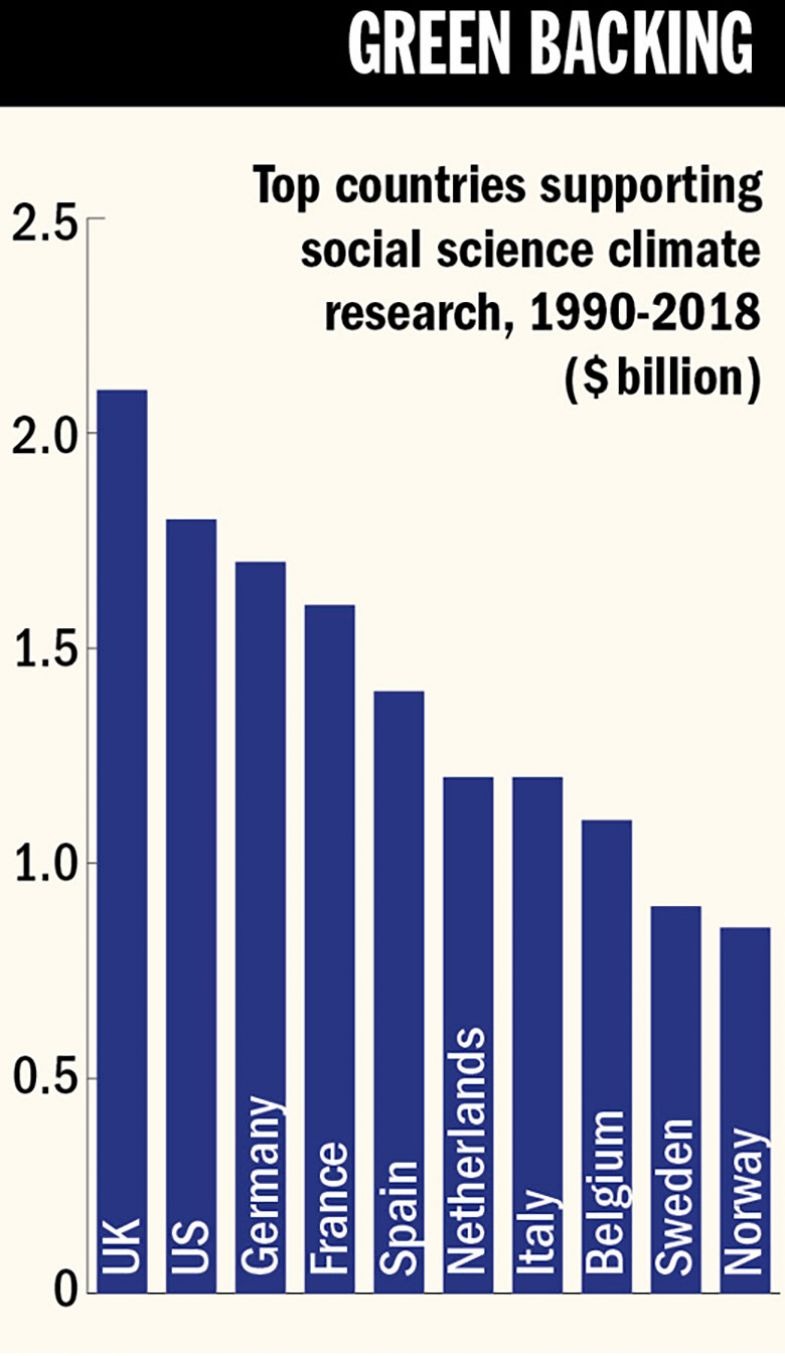

In the paper, he and Professor Overland note that the US spends $34.8 billion annually on HIV/Aids research, and, up to 2011, had invested $196 billion on space shuttle programmes. In contrast, since 1990, it had spent some $1.8 billion on climate change social science research – less than the UK ($2.1 billion) and the European Commission ($2.6 billion).

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Short shrift for social science in climate research cash

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?