The number of managers and professional staff employed by UK universities grew by about 60 per cent in 12 years as “student experience” roles doubled, while the number of teaching-only roles rose by 80 per cent, according to a report.

The paper on sector staffing patterns, published on 8 December by the Policy Institute at King’s College London, concludes that its confirmation that “both teaching-only and senior managerial and non-academic professional posts have indeed grown very rapidly” presents a case that the “internal organisation and governance of our universities requires some quite urgent attention”.

The report was written by Baroness Wolf, Sir Roy Griffiths professor of public sector management at King’s and now also skills and workforce policy adviser in the Number 10 Policy Unit, alongside Andrew Jenkins, an associate professor in the UCL Social Research Institute.

Their research involved analysis of Higher Education Statistics Agency data on staffing, plus interviews with managers at six institutions.

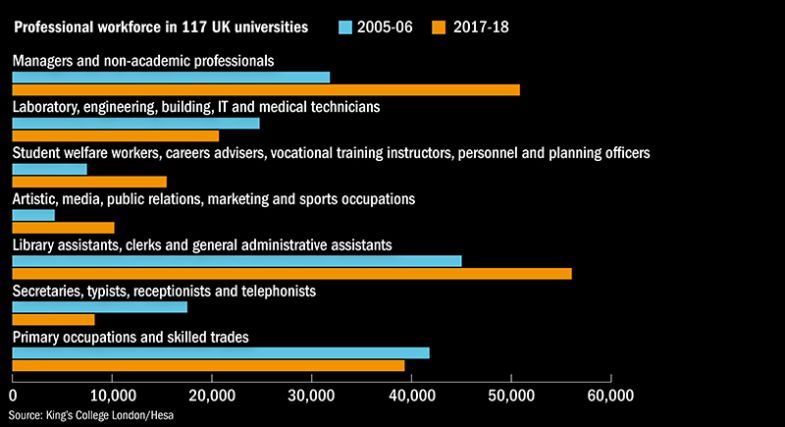

Among professional staff, numbers across seven subgroups within this category grew by 16 per cent overall between 2005-06 and 2017-18, the research finds. But within that, “the largest absolute growth was in the numbers of managers and non-academic professionals”, which expanded from 32,000 to 51,000, an increase of about 60 per cent.

“We were taken aback by how real the growth in managerial numbers was and how much it was balanced by disappearing secretarial jobs in departments [and] reductions even in lab technicians,” Lady Wolf told Times Higher Education.

Associate professional level employees dealing with the “student experience”, including welfare workers and career advisers, more than doubled their numbers, from 7,485 to 15,467, to comprise 7.7 per cent of all support staff.

“Time and time again, when we did the interviews people would say: ‘If you want to justify a new post, what you do is you say it will improve the student experience,’” Lady Wolf said.

The changing professional workforce

On teaching-only staff numbers, across 117 universities there was a “remarkable” rise of more than 80 per cent between the academic years 2005-06 and 2018-19 to almost 55,000, “about five times the rate of increase for ‘traditional’ teaching and research staff”, the report says.

More than half the growth – 14,000 from a total increase of about 25,000 – occurred within Russell Group universities.

Numbers of teaching-only staff grew fastest at universities expanding their student enrolment most rapidly – and many of those were in the Russell Group, the report says.

Across the twin workforce trends, the report argues these were “driven not only by the changing external environment” – competitive student recruitment, regulatory change or the research excellence framework – but also “by the way universities are organised and governed”, where it pinpoints a shift towards making decisions at the centre of universities rather than in departments.

“Everything we know about lean and efficient organisations, and about effective and creative academic groupings, is that they tend to be small and relatively autonomous. It’s very hard to believe that this growth in centralised administration, this growth in centralisation generally, is actually helping creative academic work,” Lady Wolf said.

“People always say, ‘What would you do about it?’ I would give more power back to the departments.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?