Globalisation, long regarded with suspicion by some, is now under full-scale attack. “Our politicians have aggressively pursued a policy of globalisation – moving our jobs, our wealth and our factories to Mexico and overseas,” said US president-elect Donald Trump in a speech in June. “Globalisation has made the financial elite who donate to politicians very, very wealthy. I used to be one of them.”

Mr Trump has lambasted free trade agreements that cover North America and the Pacific, and meanwhile, in Europe, Brexit could see the return of tariffs and immigration restrictions between the UK and the European Union. The trend is not limited to the US and the UK: a World Trade Organisation report released earlier this year found that G20 countries are now applying trade-restrictive measures at the fastest rate it had ever monitored.

However, one pillar of globalisation appears untouched – for now. Since the advent of the internet, academic research has become increasingly integrated into an open, global system of science conducted in the lingua franca of English, where findings flow freely and labs are populated by researchers from all over the world, Simon Marginson, professor of international higher education at University College London, told Times Higher Education.

In a new paper contrasting the fortunes of China, now a key part of this global science system, and Russia, which has underfunded research and has shut itself off, Professor Marginson demonstrates just how entwined research efforts now are. “Science is a single, largely open system,” he writes. This “is a remarkable change in human affairs”.

Two-thirds of the citations in this system of English language papers now come from a different country to the author. Meanwhile, the number of articles with co-authors from different countries rose by 168 per cent between 1995 and 2012, Professor Marginson finds, much faster than the overall growth of papers.

Could this global system of science disintegrate in the new protectionist world of Mr Trump and Brexit? Or will research remain a beacon of cosmopolitanism even as nationalism gains ground?

The threats to scientific globalisation fall into three rough categories.

The first is that more restrictive immigration regimes make it harder for researchers to work in other countries, making the cross-fertilisation of ideas more sluggish. Brexit could be one example of this, if it means that researchers will need visas to move between the UK and the Continent.

A second danger is that governments start to view foreign ideas with suspicion and try to stop them. Chinese politicians have issued occasional broadsides against “Western ideas” on campus, although these seem more aimed at ideas of democracy and the rule of law than the scientific method itself.

Conversely, a third risk is that security-conscious states start to view their national research results as industrial or military secrets, and prevent foreign scientists learning about them. Last year, Russian scientists warned of a “return to Soviet times” after some were reportedly told to seek permission from the security services before sending their papers to conferences or journals.

Rather like in trade, if one country closes up scientifically, others could retaliate.

“Blatant protective behaviours of individuals, or for that matter entire countries, are unlikely to go ignored for very long and will have knock-on effects,” says Robert Tijssen, chair of science and innovation studies at Leiden University, “where others become increasingly reluctant to disseminate or share information with their (former) partners in such ‘retreating’ countries”.

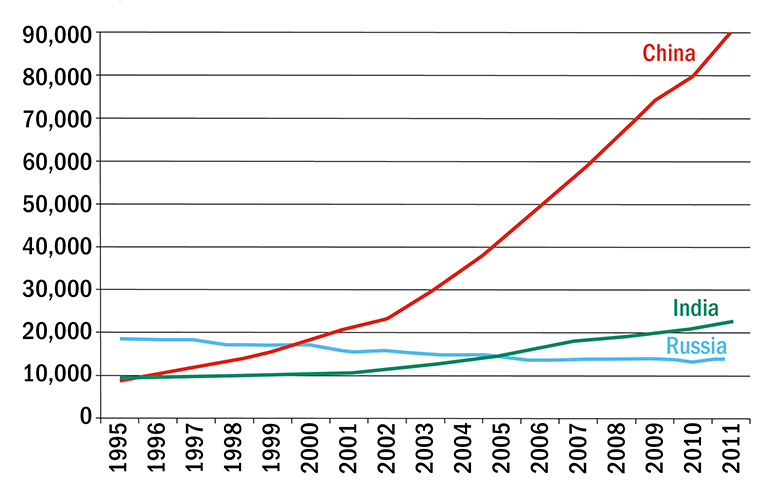

Annual output of published science papers in Russia, China and India, 1995-2011

Source: NSF, 2014/Simon Marginson

Professor Tijssen was one of the co-authors of a 2011 analysis that used an ingenious method to measure the globalisation of research. It calculated that the average distance between co-authors has grown from 334km in 1980 to 1,553km in 2009 (about the distance between London and Lisbon). One future way to monitor whether the globalisation of science has halted would be to re-run this analysis, he suggests.

Professor Marginson says that he is “quite concerned” about the risk to globalised science in a new protectionist era but that he has not seen any evidence of a backlash so far. “The period of high internationalisation [of research] could come to pass, but there’s no sign of it yet,” he says.

There are several reasons why research could remain a resiliently global endeavour.

Knowledge flows much more freely than physical goods, Professor Marginson points out; international science is “not a trading system”. “Knowledge leaks, you can’t control it,” he says.

Another reason highlighted by his paper is that more than ever, countries that cut themselves out of the global system of science risk falling behind technologically and therefore economically, much like North Korea.

Professor Marginson rings alarm bells about Russia, where the number of science papers published has declined about 1 per cent a year since 2000 (see graph, above).

In part, this is down to low funding, but Professor Marginson argues that it is also due to a “Soviet inheritance” of isolationism – an insistence on keeping findings in Russian, making it impossible to participate in the “global conversation” about science that takes place largely in English.

In 2013, the country did launch a plan to recruit 10 per cent of its academics from overseas, but the funding available is modest. In China, however, the government has pushed researchers to publish in English, collaborate with overseas partners, and sought to attract back its diaspora from the US, Professor Marginson points out – and it is now a major science power, both in terms of the quantity and, increasingly, the quality of papers that it creates.

Science may also stay global because researchers themselves are likely to kick back against attempts to limit their collaboration. “Individual scientists and scholars don’t want to be cast out of the collective – even if authorities impose restrictions on their ‘academic freedom’,” points out Professor Tijssen. “Creative people will find ways.”

And, finally, many scholars simply see problems as being impossible to solve without an international effort.

“The history of science innovations taught us that [the] mixing of researchers from various sectors of the global society regardless of their gender, ethnicity, country of origin, race and religion is the most powerful way for different peoples to find common grounds to solve problems together,” argues Omar Yaghi, director of the University of California, Berkeley’s Global Science Institute, which has set up mentoring schemes for young scientists in Japan, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Vietnam.

If this age of globalisation is indeed coming to an end, research will be “the last thing” to retreat back inside national borders, thinks Professor Marginson. The genie is likely out of the bottle: “in practice, it’s impossible to close up”, he says.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?