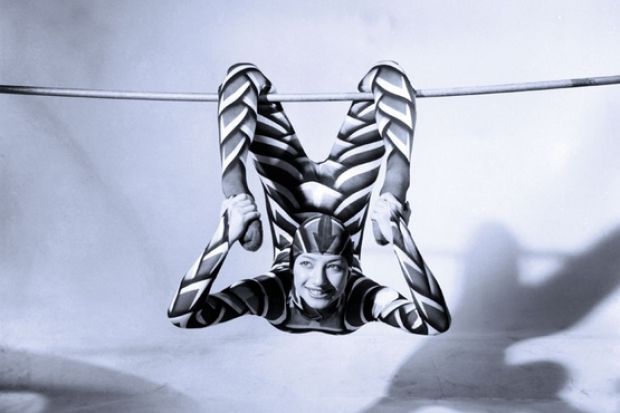

Source: Alamy

Learning should be flexible: David Latchman believes ELQ restrictions are pricing would-be part-time students ‘out of the market’

Ministers should reverse the ban on graduates accessing student loans to sit second degrees if they are to halt a “worrying decline” in the number of part-time students.

That is the view of David Latchman, master of Birkbeck, University of London, who said that the rules preventing students from receiving loans to sit lower or equivalent-level qualifications (ELQs) to those they already hold should be reassessed in light of a dramatic slump in part- time numbers.

Statistics released by the Higher Education Funding Council for England last week show that the number of Britons starting part-time undergraduate degrees has fallen by 40 per cent since 2010 - a loss of 105,000 students.

Part-timers became eligible to receive fee loans of up to £6,750 a year as part of the 2012-13 tuition fee rises, but the ELQ restrictions had undermined the policy and priced thousands of students “out of the market”, Professor Latchman said.

However, opening up loans to such students would not be as expensive as the Treasury feared, he said, as part-time students with ELQs were generally employed upon graduation, worked during their courses and could be relied on to pay back most of their loans.

“It would be in the government’s interest to provide loans for ELQ students, given their relatively high incomes and the fact they would start paying their loans back immediately,” Professor Latchman said.

Ministers believed that withholding loans from graduates would “save Hefce a sum of money”, he continued, “but it is not clear it would cost…that much”.

He added that he thought the state would get its money back “with interest from these students”.

Only 31,700 part-time undergraduates out of 154,000 entrants applied successfully for loans in 2012-13, David Willetts, the universities and science minister, revealed in Parliament this month.

Deterrent effects

Claire Callender, professor of higher education at Birkbeck and the Institute of Education, University of London, said it was clear that the student loan rules and the overall increase in tuition fees were deterring thousands of potential part-timers.

“Even those who are eligible have to think hard about whether or not it is financially beneficial to study,” Professor Callender said.

“Some institutions that were charging £300 a module are now charging £1,500. If [part-timers] have a mortgage and children, this is a big consideration and there is no certainty that they will get a highly paid job or higher paid job at the end of their degree.”

She added that losing graduates from the part-time student population risked damaging its social diversity and academic strength.

This was because the part-time sector would become dominated by those with lower entry qualifications at higher risk of dropping out and getting lower paid jobs post-graduation.

This would push up the costs to the government of providing loans to part- time students, Professor Callender said.

Meanwhile, a report for the Higher Education Policy Institute by David Maguire, vice-chancellor of the University of Greenwich, has called for an end to the “arbitrary” and “outdated” binary divide in funding for part- time and full-time students.

In the report, titled Flexible Learning: Wrapping Higher Education Around the Needs of Part-Time Students and published on 21 March, Professor Maguire says that extending loans to all part-time students would cost around £700 million a year, while offering maintenance support would cost an additional £600 million a year.

“The only realistic way of extending funding in this way would be - as many have argued - to remove the loan subsidy,” Professor Maguire argues.

“That would be a difficult and politically contentious thing to do, but it is something that will need to be considered if the encouragement of part- time education is to become something more than empty rhetoric, confounded by the reality of the new funding arrangements.”