In the 18th century, and for the modest outlay of a penny, you could go to the Bethlem Royal Hospital (Bedlam) and laugh at the lunatics. Today, you can do much the same by watching television comedy series set in universities or, indeed, by reading some campus novels. So what is so funny about universities? Here are serious institutions on the frontiers of knowledge, exploring the past and inventing the future, but somehow providing fodder for Carry on Campus. Such works are peopled by the mildly priapic, the determinedly incompetent and the resolutely eccentric, when of course none of this applies (at least not simultaneously).

In Tom Sharpe’s Porterhouse Blue (1974), adapted for Channel 4 by Malcolm Bradbury in 1987, two gross of gas-filled condoms explode, destroying much of a Cambridge college, while the same channel swiftly and entirely justifiably cancelled another campus comedy wittily titled Campus, which featured an entire phalanx of deranged faculty in a show that made Police Academy 6 seem like a Chekhovian masterwork. The American series The Big Bang Theory - Friends with a higher IQ, a triumph for the writers’ room with gags about string theory provided by academics supplementing their income - features students obsessed with Star Trek. Fresh Meat, another Channel 4 offering, presents students in search of sex, alcohol, drugs and learning of a kind not likely to be tested in their examinations. Universities, as portrayed in these works, seem to be primarily designed to provide secure accommodation for those in need of protective services. So why do I like them?

In part it is because I have written them, as Bradbury’s junior partner, but also because universities used to have an element of Bedlam about them, and I miss it. In my first job, the university’s distinguished professor of history had published a book shortly after his appointment at the age of 29. His second was published posthumously (he died when he was 66). His coffin was carried past my window, doubtless as a warning against overproductivity.

In the same department, a female lecturer announced that she had secured the services of a famous academic, but she was not prepared to tell anyone who it was.

I was a student at the University of Sheffield and cannot remember a single lecturer/professor who could be said to be entirely of this world. I was introduced to American literature by the poet Francis Berry, who was so enamoured of Beowulf and the sagas that he wore a sweater emblazoned with runic letters and called his son Scyld after Scyld Scefing (a son who went on to become the cricket correspondent of The Sunday Telegraph). He made his first entrance by throwing the door back against the wall, as Beowulf himself might have entered the Great Hall, and offering a prize for the most phallic drawing of Florida.

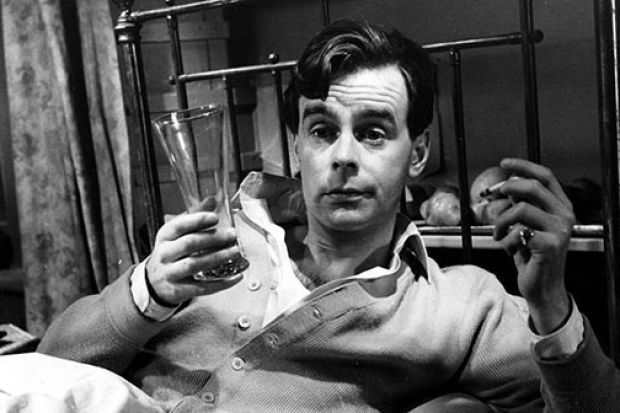

My tutor was William Empson, a man of genius with a nicotine-stained mandarin beard. When he wasn’t counting up the ambiguities, he would roll his eyes back in his head so you could only see the whites (or, more truthfully, the yellow flecked with red) and try to stuff a filter-tipped cigarette into a cigarette holder as I read out my essay in what was evidently a comforting drone, as judged by his tendency to lose all interest and stare about the room as if looking for a reason to live. He always gave the same grade - B++ - and wrote the same comment, which, over the years, he had shortened to “IOCTTO”, which meant “If one comma then the other”, as in parenthetical phrases. We would then retire to the pub, where once he ordered a round and then bolted, leaving me to borrow money to pay the bill. He was alleged to invite students back to his house, ask if they would like some tea and then pour out whisky. Another member of faculty was so scary that a female student actually ran away.

Now my point is that this is what university teachers should really be like and, in the works under consideration, they are (IOCTTO). At my own institution, many years ago, a dean was a kleptomaniac who would go to dinner parties and half inch any item that took his fancy. You may say that this was simple criminality and, indeed, he did end up in court, which gives one confidence in our legal system if not in human nature. But he brought a certain sense of danger, which I appreciated. A professor of philosophy, if a light bulb failed, would call the estates department. If it failed to respond immediately, his next call was to the fire brigade, which eventually threatened to allow the university to burn to the ground if we did not exercise control over our staff, or at least improve our light bulbs.

In The History Man (1975), Bradbury wrote an account of a school board at the University of East Anglia that devolved into farce. School boards were never like that before he wrote the book. Gratifyingly, they were often like that afterwards. Sometimes they were presided over by a genuinely brilliant professor who suffered from diabetes. As a result, part way through meetings he would get ever more belligerent until people started rooting around in their pockets to see if they could find an old peppermint or Werther’s Original to pass down to him so that his sugar balance could be restored.

Alas, as in Ecclesiastes, this too has passed away. Lecturers are required to be normal. I think it is in the contract. The decidedly odd are sent on a course by a nervous human resources department, given a mentor, referred to counselling and, in the last resort, promoted into the administration on the same principle outlined when sending Hamlet to England where the mad will go unnoticed. They still walk the earth, however, on TV, so that I personally view them with a sense of nostalgia.

It is surely time to rerun A Very Peculiar Practice, the 1980s comedy series in which the writer Andrew Davies scored his first success. The series was a response to the cuts of the period. It was set in Lowlands University, which the always trustworthy and reliable Wikipedia informs me was based on my own university, not least as an act of homage to Bradbury, who taught there. In reality, UEA wisely passed on the opportunity to allow filming of a series that featured a vice-chancellor by the name of Ernest Hemingway, later replaced by the American Jack Daniels. The series featured Hugh Grant as an evangelical preacher, not, as we were to learn, a piece of typecasting.

Of course, not all campus series are like Whitehall farces. Colin Dexter’s University of Oxford was the location for serial homicides as a challenge to a Jaguar-driving, classical music-loving detective, while the same institution, in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1945), offered a portrait of a privileged ruling class and was doubtless distributed free to members of the coalition government. This is certainly a moment for clutching teddy bears and finding God.

Of course, Kingsley Amis was one of the pioneers of the genre. Lucky Jim (1954) featured a young lecturer in medieval history at a redbrick university in the Midlands (Leicester) who finds himself at odds with the system and ends his career with a drunken lecture shortly before collapsing. Amis, a lecturer at what is now Swansea University, was followed by Bradbury and David Lodge, also university teachers, and by Howard Jacobson, who taught at a polytechnic before the Conservatives scattered pixie dust on them, making them into universities. In Coming from Behind (1983) he creates a Jewish lecturer who feels out of place and fantasises about a building in Hampstead called Bradbury Lodge where writers get together to despise him.

Bradbury once asked why the campus novel was so called when works about salesmen were not called salesmen novels and books set in hospitals, hospital novels. In truth, his novels, and indeed those of Lodge, were not about universities but a changing social and intellectual world. Both also featured overseas universities. In Unsent Letters: Irreverent Notes from a Literary Life (1988), Bradbury caught the casual world of German higher education in the form of a letter sent to him: “Herr Doktor Professor Bradburg, Excuse please that I address you so, but I think in your country you do not mind such informality…I am advanced student in Anglisten-Studien at Lebfraumilch University. I have already passed the examens for my Arbeitsnachtrichen, my Fernspreche and my Hinauslehen mit Predikat.” He was a great believer in the principle that when you’ve lost an empire, all you’ve got left is condescension. In the same decade he published Cuts (the title of which reflected Margaret Thatcher’s weapon of choice with respect to culture).

The campus novel is not unique to the UK. For example, Mary McCarthy’s The Group (1963) and Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot (2011) are not without humour. McCarthy’s novel is concerned with a group of women tackling problems of sex, taking as its models real women she had known at Vassar College, much to their irritation. Predictably, Norman Mailer welcomed it as a “trivial lady writer’s novel”.

The US campus novel, though, tends to be the site of rather more serious concerns than in the UK. There are not a lot of laughs in Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (1992) or Philip Roth’s The Human Stain (2000). The fact is that the tradition of the English novel (as opposed to the American, Twain aside) is in essence a comic one, from Smollett and Sterne to Austen and Waugh. The campus novel is a tributary of the major river.

I remember once a German academic attacking the British use of self-mockery as a concealed arrogance: we were so certain of ourselves, he thought, that we believed we could parade our supposed weaknesses, knowing that we did not believe in them. Perhaps that was his intellectual equivalent of going round the end of the Maginot Line, but maybe he was right. We mock ourselves in universities, write or read campus novels, watch TV series, not because we believe ourselves lunatics in an asylum, but because we wish to conceal from others, and perhaps from ourselves, that the asylum begins just beyond the campus boundary. It would be a mistake to believe that the ironic or even farcical commentary they offer is designed only to address what is happening within those boundaries.

Edward Albee chose to set Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962) in a university not simply because it justified the highly articulate verbal battles of its central characters, but also because of his sense that alien ideas had penetrated what should have been a place uncontaminated by corrupting values. Not for nothing does he locate his university in a town called New Carthage, the original Carthage having been totally destroyed.

In 2010, Frederic Raphael, who in 1976 wrote The Glittering Prizes, a BBC TV series about the fate of a group of University of Cambridge students, observed that the prizes on offer were no longer what they used to be, no longer awarded by those in government but by Simon Cowell. Today’s elite, he suggested, are well advised not to advertise their brains, which is perhaps why we don’t. Who, he asked, would guess that Jonathan Ross has a degree? “Most of what the universities used to teach”, he suggested, is being judged redundant, and “unless what’s left of their Science Parks can come up with paying propositions, they’ll be for the chop too and all. Glittering prizes? Honestly, today’s guys and dolls would sooner have the money.”

Are the self-effacing, self-parodying campus novels a sign of confidence, then, the ability, usually by academics or graduates, to make fun of themselves? Or are they an acknowledgement that universities have become a side-show, invited by government to demonstrate their “relevance”, “impact”, “outreach”, anything but their real reasons for being? Bradbury was always disturbed by the suspicion that The History Man, with its portrait of a venal radical, had played into the hands of Thatcher, whose cuts to university budgets would be replicated the next time Conservatives got their hands on the public purse. He was not wrong. Perhaps that is the reason this and his other novels are to be reissued this September.