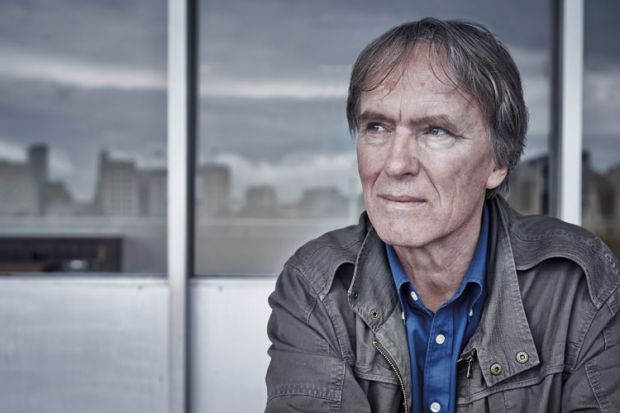

Source: Peter Searle

This still left open the question of whether his father, Bill, was one of the (comparatively) good guys or someone who was particularly ruthless

For Bart Moore-Gilbert, professor of postcolonial studies and English at Goldsmiths, University of London, his new book, The Setting Sun: A Memoir of Empire and Family Secrets, is “a sort of detective story. Ironically, given that my father was a policeman, he is the accused and I am the detective trying to piece together the facts.”

Born in 1952, Moore-Gilbert spent his early years in what is now Tanzania and describes himself as “belonging to the last generation who spent their childhood in the empire…By the time I was 15 it was a world which had disappeared.” Many of his subsequent intellectual interests, in an academic career spanning four decades, have come from “wanting to understand the whole colonial culture and where I came from”.

One Friday afternoon in 2007, however, an email that arrived out of the blue – Moore-Gilbert almost deleted it in a hurry to clear his inbox before going to the pub – led to his research taking an unexpected turn. The message, from an Indian researcher called Professor Bhosle, was seeking information not about his own work but about Moore-Gilbert’s father, who had died when he was a child. Did he have any papers to illuminate why his father, an officer who “had the distinction of having successfully suppressed the revolt of the Hoor tribes” in Pakistan, “had been especially brought to Satara District to deal with the powerful political agitation then going on”?

Although aware that his father had served in the Indian Police in the nine years leading up to Indian independence in 1947, Moore-Gilbert knew little else and it came as a surprise to learn that he had been involved in counterinsurgency. As an academic whose own political position is critical of the “essentially indefensible” imperial cause in general and some of the measures introduced in India in the 1940s in particular, the email opened up a hitherto unknown – and potentially painful – aspect of family history.

Moore-Gilbert was just 12 when his father, Bill – then working as a game warden – was killed in an aircraft crash while on a United Nations-funded humanitarian mission looking for places to settle Tutsis fleeing Hutus in what is now Rwanda. (He was told about his father’s death, he tells us in the book, by the colonel who served as a housemaster at his English school. The colonel’s wife showed her sympathy by bringing him “a caramel éclair on a white plate…She presents it to the boy formally, as if he’s won a prize.”)

Deeply scarred by this tragedy, he would return, almost obsessively, to Africa in later life, trying to track down Kimwaga, the man who had been his childhood minder in Tanzania.

Before going to Durham University to study English in 1972, he spent a year teaching in a Kenyan bush school near Lake Victoria. The O-level syllabus included a good deal of African literature – books, he recalls, “much more about communities, social justice and history than I was familiar with from A-Levels in England” – and it was this that first sparked his interest in postcolonial themes. Yet there was little opportunity to study such material at Durham (“I did three years of Anglo-Saxon and would much rather have spent the time on postcolonial history”) and plans for a PhD on a postcolonial theme at the University of Cambridge also fell through; a casualty, he realised later, of “the crisis of traditionalists versus modernisers”.

After a doctorate at the University of Oxford on Rudyard Kipling, Moore-Gilbert secured a job as senior lecturer in English at what was then the Roehampton Institute of Higher Education. He moved on to Goldsmiths in 1989. As well as a book on Kipling, whom he sees as “an absolutely superb exponent of the short story” despite all that is “horrid, disagreeable and quite racist” in him, he has edited a collection called Writing India, 1757-1990: The Literature of British India and written studies of postcolonial theory, postcolonial life writing and Hanif Kureishi.

I meet Moore-Gilbert in a Japanese cafe near the British Library. Since 2009, he has been on a half-time contract at Goldsmiths, he explains, because “I had been an academic for a long time and wanted to do other kinds of writing…You never see people reading academic books on the Tube!”

His latest research project, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, is designed to shed light on the question of “How might postcolonial studies be reconfigured by paying some serious attention to Israel/Palestine?” He is also working on a novel set during the British Mandate for Palestine, which he hopes to submit to a publisher together with another novel set in the Pyrenees, so as to “suggest that I am not just a one-hit wonder but have some staying power”.

This shift to more creative forms of writing started with The Setting Sun.

When the British ruled India, the biggest mistakes they made, Moore-Gilbert argues, were “not consulting the Indian people about whether to go into the Second World War – they probably would have supported it – and the emergency regulations imposed in the name of ‘security’. Those were a disaster, but they were so afraid of losing control and Japan potentially taking over that they overreacted.”

Yet within these broad parameters, this still left open the question of whether his father, Bill, was one of the (comparatively) good guys, a run-of-the-mill servant of Empire, or someone who was particularly ruthless or even cruel in carrying out his unsavoury duties. The Setting Sun describes Moore-Gilbert’s quest to find out and the often acute tension this raised between “the emotional loyalties formed during childhood and the postcolonial political ethics I’ve acquired as an adult”.

Perhaps rather surprisingly for an expert on Indian writing, Moore-Gilbert had never visited the country, largely because he thought that “the India I was primarily interested in – the India of the Raj – had disappeared”. He now sees that that was a mistake: “I was astounded by how Mumbai is like being in the centre of Manchester…The Raj infrastructure is still there, but totally swamped by the sheer number of people.

“There was a very big mismatch between what I expected of India and my actual experience. I expected it to be much less hectic and to be quite threatening, but I never felt I had to keep an eye on my belongings.” When he chanced upon a wedding reception in the street, he tells me, “the lights and smells and noises, the constant sense of spectacle” meant that “you can just stand and gawp all day long”.

As a result, he describes the first draft of the book as “a mess of travel writing”, but gradually “what you might call the plot became clearer and clearer”.

The most powerful statement of the case against his father appears in a book by Dr A. B. Shinde called The Parallel Government of Satara: A Phase of the Quit India Movement. This describes how, in 1944, “the police lost self-control and perpetuated atrocities on the people…Moore-Gilbert, the Additional DSP [deputy superintendent of police], Satara, got wide notoriety for his ruthlessness with which he carried out these raids…[Those living in the village of Chafal] were rounded up and herded together like cattle in the temple: they were deprived of their clothes and ruthlessly beaten up…Cow dung and mud were thrust in the mouths of some while others were made to lie prostrate on the ground and nearly frightened out of their lives by holding bayonets to their throats; even old men were not spared.”

I was 12 when my father died, so I knew him properly for only about nine years. My research has given me a chance to double that

This may sound fairly incontrovertible, but Moore-Gilbert’s journey led him to many different sources and a number of eyewitnesses, from the Chafal villagers quoted in depositions to former police colleagues and even surviving underground leaders. A man who worked closely with his father was warmly appreciative when they met in person but also gave him copies of a memoir and a factually based detective novel that offer two much less flattering but very different portraits of Bill. A former “field marshal” of the parallel government refers to “Gilbert” as “a terrorist”, while acknowledging that “he wasn’t as bad as the others”. Another rebel provides much more comic accounts of avoiding capture from Bill and the British by dressing in a sari and hiding in a well.

There are a number of explanations for such discrepancies. Moore-Gilbert tells me, for example, about “the dominance of the nationalist narrative” in much Indian historical writing, which can lead to “ludicrously exaggerated criticisms of colonialism”. Those working outside a few elite universities, he adds, “can only get published if they get patronage, which imposes its own pressures on what you write”.

On one level, then, Moore-Gilbert just had to accept that he would never know the whole truth about his father, since the historical record is too confused and contradictory. But alongside the historical analysis, he brings his personal responses to bear.

“What struck me again and again about my father’s involvement in India,” he reports now, “was how young he was, given his responsibility and all the pressure from above, with superiors telling him about everything that’s destabilising the province and to use any method necessary – [his former colleague] Modak is insistent on that – but to just get rid of the problem.” Few of his PhD students, he reflects in the book, would have been very effective in “taking on well-organised, armed insurgents, in a district the size of Wales, and equally mountainous in parts”.

As it happens, there is one rather frightening episode described in The Setting Sun, where Moore-Gilbert and his guide are chased by a group of angry thugs and “some perverse instinct made me run at the boys. Attack as the best form of defence.” Afterwards, he recognises a strong feeling of “I just want them punished” for harassing him and wonders with a certain sympathetic understanding whether “circumstances sometimes goaded Bill into the same animal reflex of rage”.

Even more striking, perhaps, Moore-Gilbert offers some evocative and often moving episodes from his childhood – his father teaching him the facts of life “with the aid of a cold sausage”, beating him for some minor misdemeanour and carrying on at least one adulterous affair – as “evidence” for the kind of man Bill was. His emotional quest is totally integrated with the more documentary approach one expects from an academic historian, although both ultimately prove inconclusive.

So what had he learned from his Indian journey and many years of honing it into a compelling narrative?

“I was 12 when my father died,” Moore-Gilbert responds, “so I knew him properly for only about nine years. My research has given me a chance to double that – and to see him, for the first time, as adult to adult, not child to adult. I had my childhood memories of my father and felt that’s all I had, that there would be no opportunity to change those, that I’d just carry on in the same groove remembering this heroic figure who towered over my childhood. Now I feel I’ve come to know him again on a much deeper basis.”