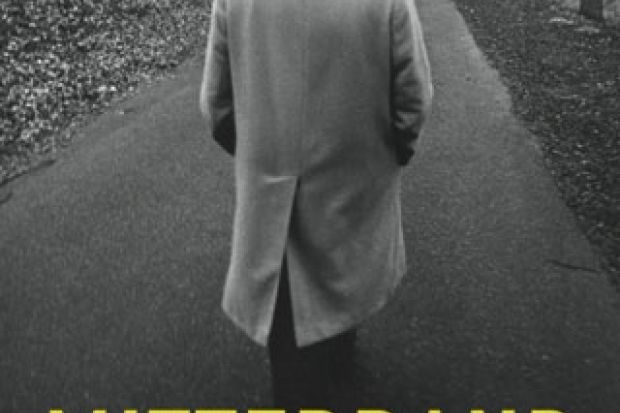

Sir David Bell, vice-chancellor, University of Reading, is reading Philip Short’s Mitterrand: A Study in Ambiguity (Bodley Head, 2013). “Following his momentous biographies of Mao and Pol Pot, Short’s Mitterrand is an authoritative account of the life and times of the Fifth Republic’s most enigmatic president. From Vichy employee to the Élysée Palace, Mitterrand overcame many political mishaps and personal entanglements that would have deterred a weaker man. Life mirrored his presidency, which Short describes as one of ‘ambiguity, mistrust and solitude’.”

Sir David Eastwood, vice-chancellor, University of Birmingham, is reading C. J. Sansom’s Dominion (Pan, 2013). “Historical novels are often poor history and indifferent fiction. This, however, is brilliantly plotted, and historically wholly plausible, set in a Britain that signed an armistice in 1940. The details delight, despite the bleakness of the storyline. Moreover, what Sansom stands for both in the novel and the historical note is profoundly right. Only one slip: even if Britain had capitulated, Oxford would still have awarded DPhils, not PhDs.”

Graham Farmelo, by-fellow at Churchill College, Cambridge, is reading Sarah Dry’s The Newton Papers: The Strange and True Odyssey of Newton’s Manuscripts (Oxford University Press, 2014). “The fate of Newton’s manuscripts, now widely dispersed, has long fascinated scholars. By identifying the roles of a host of collectors in securing various parts of the collection, Dry does full justice to a fascinating story. But this is more than a detective story; it sheds bright light on the range and development of this most brilliant – and most elusive – of minds. Pure joy.”

Liz Gloyn, lecturer in Classics, Royal Holloway, University of London, is reading Kathryn Welch’s Magnus Pius: Sextus Pompeius and the Transformation of the Roman Republic (Classical Press of Wales, 2010). “History has portrayed Sextus Pompeius, younger son of Pompey the Great, as an isolated pirate on the fringes of a crumbling state – but history is written by the winners. Welch painstakingly recovers his role in defending the Roman Republic after his father’s murder in Egypt, making us reconsider our views on the shift from republic to principate in the process.”

R. C. Richardson, emeritus professor of history, University of Winchester, is reading Geoffrey Grigson’s The English Year (Oxford Paperbacks, 1984). “Now rather out of favour, Geoffrey Grigson (1905-85) was a prolific poet, literary editor, anthologist, art critic and travel writer who excelled as a commentator on the English countryside. This evocative compilation, drawn chiefly from 18th- and 19th-century diaries and letters and illustrated with sketches by Constable, celebrates the rhythms of the changing seasons as well as the specifics of time and place and can be approached with different reading strategies in mind.”