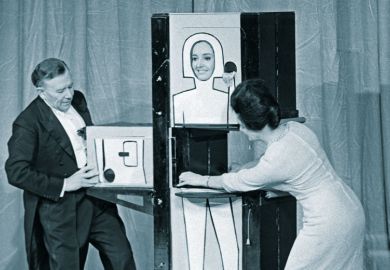

Source: Alamy

Warning signs: if the marking boycott proceeds and employers start docking pay then strike action may follow, experts say

Universities could face a “winter of discontent” of escalating industrial action if academics are docked pay for participating in a marking boycott over proposed pension reforms, it has been predicted.

While talks between employers and union representatives may be brought forward ahead of a planned assessment boycott, starting on 6 November, the two sides appear unlikely to reach a compromise over plans to alter the benefits paid by the Universities Superannuation Scheme.

Universities UK says that the University and College Union has “offered no proposals for reform of the USS”, but a recovery plan to fill a deficit of at least £8 billion is “unavoidable”.

Sally Hunt, UCU general secretary, claims that UUK’s proposals are “full of holes” and based on “misleading” information, while the union disputed the reasons for reducing the deficit.

Gregor Gall, professor of industrial relations at the University of Bradford, said he believed that the marking boycott called at pre-92 universities would go ahead as planned.

“The signs are that we are in for a ‘winter of discontent’ that will dramatically escalate when employers start docking pay,” said Professor Gall. “This could then lead to strike action as well in order to allow other UCU members to show solidarity to their fellow union members.”

Staff resolve ‘stronger’

Hundreds of thousands of students at 69 universities may be unable to sit exams if the action goes ahead, nor will they receive essay marks or feedback from their tutors.

The huge majority in the recent UCU ballot – 87 per cent of voters backed action short of a strike – suggests that staff resolve would be stronger than that shown earlier this year in the national pay dispute, Professor Gall added.

“UCU members are prepared to dig in on pensions because pensions have a more lasting impact on their standards of living,” he said.

Roger Seifert, professor of human resource management and industrial relations at the University of Wolverhampton, said the swift move to a marking boycott showed that the UCU had learned lessons from the last dispute, which saw support for strike action wane.

“Boycotts quickly reach into the heart of the university’s core business of teaching and marking,” said Professor Seifert.

Despite beginning in November, boycotts are “viable as more and more students need their work [verified] throughout the year”, he said. However, he added that they were also “problematic” because non-academic staff could not take part.

Christopher Mordue, partner at Pinsent Masons solicitors, which advises universities on employment issues, said that in his view a boycott’s impact “may be limited at this time of year”. He did not expect universities to withhold pay immediately, but “there is every sign that universities will be prepared to do this as soon as there is appreciable impact on students”.

“The days of disruptive action being taken without financial consequences for those taking part are long gone,” said Mr Mordue.

However, universities are in a difficult position over pay deductions because “individual institutions have little scope to resolve [the dispute] themselves”. Indeed, many institutions have expressed concerns over the UUK proposals, with some echoing the UCU’s belief that major reforms may be unnecessary because the fund’s deficit will fall over time once gilt yields recover from a historical low point.

In its response to a UUK consultation on USS reform, the University of Essex said that employers should consider a more gradual approach to pension reform.

“To jump, in a single bound, to a long-term solution risks unnecessary reductions in the rate of growth in membership of the USS,” it says.

In its response, the University of Cambridge says that the assumptions made by the USS actuary “may be overly prudent”, while the University of Warwick says it is worried that “unnecessarily pessimistic assumptions…may be forcing much starker reductions”.

The University of Oxford has said it requires more information to address employee concerns that “this valuation and associated benefit changes truly reflect the long-term financial situation of the scheme”.

In a statement, UUK said that the USS falls under the remit of The Pensions Regulator and had to meet certain minimum levels of funding.

“We are keen to hear about the UCU’s alternative proposals for reform to address the very substantial deficit and risks within the scheme,” said a UUK spokesman, who said it is willing to meet “as soon as possible” for further negotiations.

The UCU has said that it is keen to bring forward talks, but has claimed that the UUK has refused to negotiate and presented its plans as a “fait accompli”.