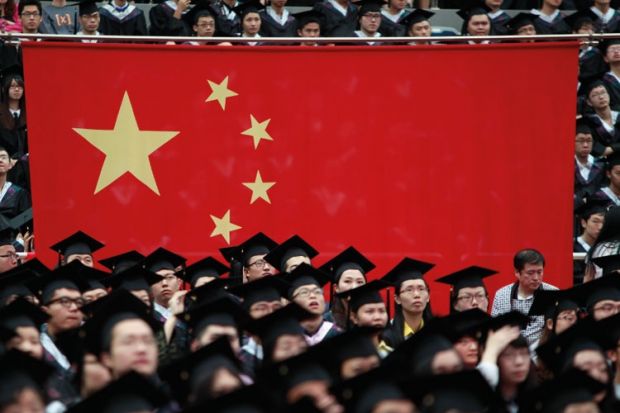

There is a warning about English universities’ “overreliance” on China in an analysis of Higher Education Statistics Agency data by the Higher Education Funding Council for England, published on 18 February.

The report says that full-time taught master’s courses in England “rely primarily on international demand”, with non-UK learners making up 74 per cent of the 2013-14 intake.

Non-European Union entrants represented 62 per cent of new students, with the 29,360-strong Chinese contingent accounting for 25 per cent of the total alone. This was up from 23 per cent in 2012-13.

Home students made up only 26 per cent of the intake to full-time taught master’s courses in 2013-14, down from 34 per cent in 2005.

The report warns of English universities’ “high degree of dependence” on China.

“A combination of continued growth from China coupled with decline or decelerated growth from other countries has led to an overreliance on China at postgraduate level,” it says.

Across all full-time postgraduate courses in England, Chinese students represented 37 per cent of all non-EU entrants in 2013-14, compared with 25 per cent in 2010.

In contrast, Indian students made up 8 per cent of the total, compared with 18 per cent in 2010. This represented a drop of 7,600 (54 per cent) in the total number of Indian students starting postgraduate courses compared with three years ago.

The number of Chinese students starting full-time postgraduate courses in 2013-14 was up 9 per cent (2,615 students) on the previous year alone, while a 30 per cent rise in the number of Malaysian entrants (500 students) was also significant.

The report questions how sustainable dependency on China and Malaysia is in the medium to long term, due to demographic changes and the development of the education system in these countries.

“Growing domestic capacity and continued investment in education systems may create an attractive and economically viable proposition for some of the students in the East Asia region seeking overseas education,” it says.

Beyond China and Malaysia, growth at postgraduate level was driven by countries with scholarship programmes, such as Indonesia and Iraq, the report says.

But this was described as “an area of vulnerability if these countries shift their funding priorities”.

Overall, the number of non-EU entrants to postgraduate courses in 2013-14 was up 6 per cent (5,060 students) on 2012-13.

The report also looks at undergraduate recruitment and says that the number of non-EU entrants was up 8 per cent (3,960 students) in 2013-14 compared with the previous year.

Growth from China slowed to 3 per cent, while the decline in Indian recruitment all but levelled out, dropping by 15 students.

While there was a 7 per cent increase (1,200 students) in EU undergraduate recruitment year on year, this was still 16 per cent (3,745 students) below 2010 entry levels.

In particular, recruitment from Germany and France was down 42 per cent (940 students) and 30 per cent (735 students) respectively compared with 2010, with increased tuition fees and demography thought to be factors.

In contrast, countries with high levels of graduate unemployment, such as Italy and Spain, sent increased numbers of students to England.