A number of things struck me as I drove the 45 minutes or so from the hotel district of Sandton to Soweto during a visit to Johannesburg earlier this year.

One is that Soweto is vast, and only small areas could be classed as slums – it consists mainly of well-maintained, if boxy, brick houses, each with a solar panel on the roof.

But before you get to Soweto, you pass through a lot of semi-rural scrubland that offers some clues about why the former South Western Townships were here in the first place.

Johannesburg is a city built on gold. The visible clues include yellowing hills of earth that has been chemically filtered to extract flecks of precious metal, and the eucalyptus trees, with their pale trunks and bluish leaves, which are everywhere but are not African at all.

The gum trees were introduced by Australian gold prospectors who needed a fast-growing, rock-solid timber to hold up the roofs of tunnels deep under the ground.

But while these miners brought trees with them, both the labour they used and the gold that made them rich were African through and through.

Today, soaring global demand for other minerals has led to mining giants redoubling efforts on African soil. But there is another area of big business that is advertised on the drive to Soweto. Prominent among the odd mix of goods and services offered on roadside hoardings (plastic surgery, funerals, particularly lurid tabloid newspapers) is private higher education.

As is the case for many internationally mobile students who come to study in the US, the UK or Australia, the hoardings tend to focus on business courses and MBAs.

- View the best universities in Africa 2016

This, no doubt, is driven by demand, and by the fact that the broad public good offered by less obviously cashable disciplines isn’t of interest to the for-profit providers responsible (even in the UK, the private providers tend to cherry-pick law and business).

But it’s no good simply raging against the for-profit model, as it clearly has a part to play in a continent with far more demand for higher education than can be met without it.

What matters is quality and relevance, and a guarantee (so far as one can be achieved) that students are being helped to improve their lives rather than exploited.

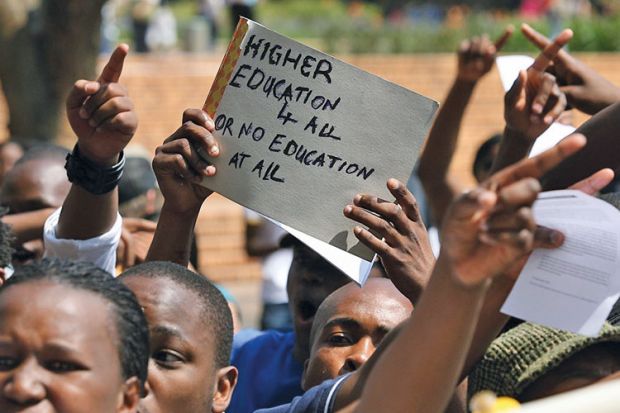

Sensitivity to this danger is illustrated by the tuition-fee protests in South Africa this week, which have forced several of the country’s largest public universities to suspend lectures.

The point was emphasised at the Times Higher Education Africa Universities Summit in Johannesburg in July, in the context of foreign investors seeing African students as a new seam of gold to be profited from.

In our cover feature, we look in detail at the issue of for-profit higher education in the continent to assess whether the right balance is being struck.

It’s a vital question, because as Thabo Mbeki, the former South African president, told the THE summit, education must play a central role in the development agenda if Africa is ever to advance as the world hopes it will.

Get the balance wrong, and we end up with further exploitation, because as another of the speakers at our summit observed: “the poor are willing to pay for bad education.” And that’s a warning that applies to the US, and the nascent for-profit sector in the UK, too.