Nearly four out of 10 new academic jobs created in England over the past decade were filled by European Union nationals from outside the UK, a study says.

Research by the Higher Education Funding Council for England found that EU scholars accounted for 12,635 of 31,950 new academic posts created between 2004-05 and 2014-15 (39.5 per cent).

The total number of EU researchers employed in English universities increased by 124.3 per cent, from 10,165 to 22,800.

The analysis, based on Higher Education Statistics Agency data, underlines the importance of EU recruitment to the university sector at a time when the UK’s membership of the union is being debated.

Over the same period, the number of non-EU academics employed by English institutions rose by 58.6 per cent, from 10,770 to 17,085. This meant that they accounted for 19.8 per cent of the overall increase.

In comparison, the number of UK academics increased by only 15.8 per cent, from 82,260 to 95,260. As a result, they represented 40.7 per cent of total growth.

Stephen McDonald, a senior economist for Hefce, said that it would be “easy to speculate that the increase in international staff might be either squeezing out UK nationals or the result of declining domestic applications following a fall in real salaries in the sector”.

But, he said, the data offer “little support” for this, since the number of UK nationals working in English universities had increased in all but one subject area over the past two years (the exception being biological sciences).

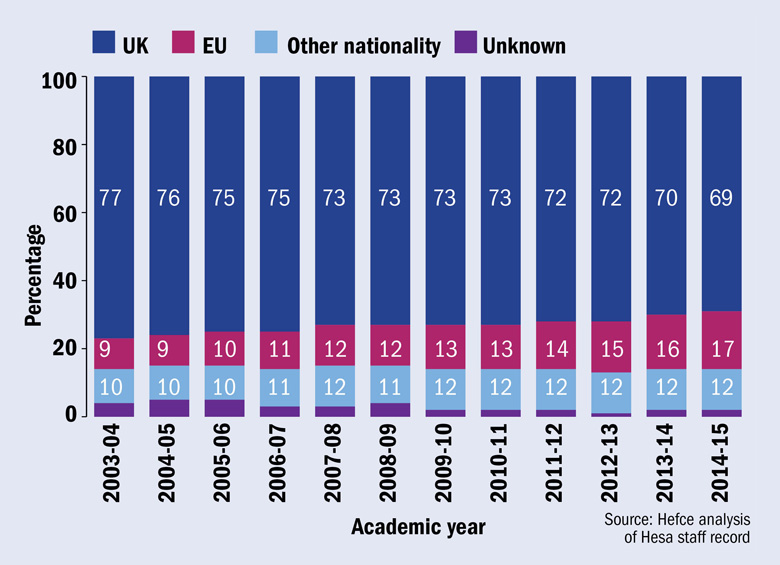

Changing proportions of nationalities among academic posts in England, 2003-04 to 2014-15

There was also evidence to suggest that the non-UK recruits were of a high calibre: they were more likely to have been submitted to the 2014 research excellence framework than UK nationals, and were disproportionately found in highly selective and specialist institutions.

“It therefore seems that in a period of large expansion of the academic workforce, English universities have increasingly needed to recruit globally to be able to meet their demand for high-quality academic staff,” Dr McDonald said.

The analysis highlights big increases over the past six years in the number of academics at English universities from several southern European countries: Portugal (up 160 per cent), Spain (84 per cent), Italy (83 per cent) and Greece (71 per cent). Public sector austerity in these states will have restricted career progression and research funding, Dr McDonald said, “all of which will have encouraged ambitious academics to migrate”.

There were also big increases in the number of academics at English universities who were from countries that recently joined the EU, such as Romania (up 85 per cent) and Poland (up 82 per cent).

Since 2008-09, there have also been increases of about 30 per cent in the number of US and Canadian academics at English universities which, Dr McDonald said, “could be interpreted as a reassuring signal of the relative attractiveness of the English higher education sector in an internationally competitive environment”. However, there was a 6 per cent drop in the number of Australian academics in England.

Apart from modern foreign languages, overseas academics were most likely to be found in science, technology, engineering and mathematics subjects, which tend to be hard to recruit into. They were least likely to be found in vocational subjects such as education and nursing.