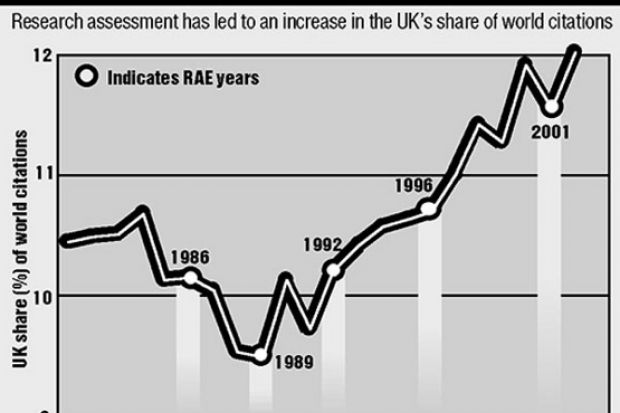

The research assessment exercise has driven up the UK's share of world research citations, a conference on publishing and the RAE sponsored by The Times Higher heard this week.

According to higher education research company Evidence Ltd, the UK's share of world citations rose from 10.5 per cent in 1981 to 12 per cent in 2002.

"There was a change in culture and attitude some time in the 1980s that has led to ongoing improvement in the share of citations," said Jonathan Adams, the director of Evidence, speaking ahead of the conference Publishing and the RAE at University College London, which was organised by the Publishers Association.

Dr Adams said: "An increase in the share is the same thing as saying an increase in relative quality. There's an extraordinary amount of activity that's pretty competitive in world terms. There could be manipulation of figures, but you can't make a whole country look better even if you can change things at the edges."

Papers published in journals as a percentage of all publications listed in RAE submissions increased between the 1996 and 2001 exercises, said Dr Adams. In science subjects, the rise was from 90 per cent to 96 per cent; in engineering, from 57 per cent to 78 per cent; in social sciences, from 42 per cent to 54 per cent ; and in humanities, languages and arts from 33 per cent to 37 per cent.

The greater the number of articles published, the greater the proportion appearing in leading research journals, Dr Adams said.

"The shift in engineering is very interesting. It was clear that conferences were the key medium for communicating research, but in terms of what was submitted to the RAE it was articles."

For social sciences, the number of articles published in journals listed in the science citation index ISI dropped from 1,122 in the 1996 RAE to 1,106 in the 2001 RAE.

Dr Adams said: "This raises the question about whether ISI data are a good performance indicator for them."

He believed universities should stop pushing academics to publish in what are perceived to be the most prestigious journals.

"Getting published in a better journal does not improve the quality of research and it will have less impact overall. This pressure to publish in prestigious journals is an extremely unfortunate tendency," he said.

"For instance, soil science is not prestigious, but when you compare soil science research globally it's of a very high standard.

"Academics know which journals they should use to reach the right audience and it is critical for environmental change and management," Dr Adams explained. "The worst thing universities can do is force researchers to publish in higher-impact journals that don't reach their audiences."

John Beringer, pro-vice chancellor at Bristol University and chair of the RAE's biological sciences panel, also voiced concern about the emphasis placed on publishing in the "right journals" ahead of the next RAE.

"When I first started doing research, I turned down a request by Nature to do a review, not realising how important it was. That some people feel driven by Nature is sad," he said.

John Thompson, a sociology professor at Cambridge University, giving the academic's view at the conference, said: "What's happening is that monographs and a selective range of peer-reviewed international journals will be the most highly valued."

He also believed the RAE had led to a systematic devaluation of other kinds of pedagogic output, for instance writing textbooks.

anthea.lipsett@thes.co.uk </a> <P align=center> <P align=left> Source: Evidence

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?