Try to outline the state of the world in a single book, and provide some future pointers. You will fall short. Authors know this, yet keep trying. Internet be damned: books are still where we do this kind of thing. The urge to make sense of the times endures, even though it’s impossibly hard.

This particular effort, from the far-sighted Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford, seeks a middle ground – between the hell-in-a-handcart mood that afflicts those fixated on 24-hour news, and the slack-jawed cornucopianism of techno-optimists indifferent to politics. There is idealism and optimism here, but tempered by realism about daunting risks.

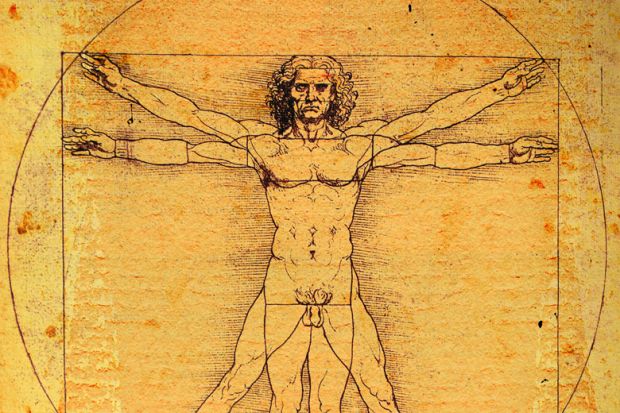

Ian Goldin, director of the Oxford Martin School and a former vice-president of the World Bank, and Chris Kutarna, a consultant, entrepreneur and fellow of the school, argue that our current state needs to be seen in historical perspective. Specifically, they suggest that our time can be regarded, loosely, as a new Renaissance, and that we should look to the first one for insights into how to manage our problems.

There are some grounds for this, I suppose: new communication technologies, expansion of trade, a burgeoning of ideas that bear fruit as they interconnect, rapid scientific advance. But the notion that a flowering of genius 500 years ago models our era does rather skate over all the things that happened in between. And the strain of the analogy occasionally tells. “Brief, quick, and cheap, printed pamphlets were the tweets of half a millennium ago”, they assert, implausibly. And “Shenzhen, in China’s Pearl River Delta, became the modern day Seville”. It may work for some readers: for me, this kind of thing is more of a hindrance than a help.

That said, there are plenty of concise appraisals of where we’re at, globally, here. They’re generally well informed, if noticeably weaker in science than elsewhere. And the authors make lots of sensible, hopeful suggestions about how we might navigate our century. They are determinedly unradical (the word neoliberalism does not feature in their account of recent history), although robust on tax reform. They are generally pro-immigration, anti-regulation and pro-innovation – not every new idea is a good one, but in a “Renaissance moment” that should be the default assumption, they urge.

They generally eschew simple solutions, although they sometimes settle for commonplaces or vague generalities. Cities need to increase the supply and density of housing, especially affordable housing for young people, we are told. Perhaps their enjoinder to “let go of comforting myths” and “champion critical thinking” will help.

Overall, the authors’ intellectual honesty allows a pessimistic counter-point to their general effort to accentuate the positive. Extremism is here to stay, they conclude. Most remedies for what ails us will generate new problems, even if they diminish old ones. And even where actions needed are clear, they observe sadly, “for the most part we don’t – and won’t – do the things we know we ought to”.

Goldin and Kutarna end with some direct advice about how to approach the century’s challenges. Again, it’s pretty general – and reads like a self-help book whose authors’ hearts weren’t quite in it. Strive for a long-term view; be bold; cultivate new perspectives and new experiences; recognise that better futures won’t just happen but have to be worked at.

These apple-pie prescriptions inevitably disappoint. Age of Discovery succeeds, nevertheless, in convincing that this is an uncommonly interesting time to be alive, with unusual levels of promise – and peril. That itself is a spur to trying to come up with proposals for action worked through in more detail, and then pursuing them.

Jon Turney, formerly lecturer in the department of science and technology studies at University College London, is author of The Rough Guide to the Future (2010).

Age of Discovery: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance

By Ian Goldin and Chris Kutarna

Bloomsbury, 328pp, £18.99 and £14.99

ISBN 9781472936370 and 6387 (e-book)

Published 19 May 2015