Design is everywhere; everything we use is designed, from the tissues into which we blow our noses to the safety evacuation procedures at our local cinemas. It is surprising, therefore, that the discourse of design is not more popular and more influential. Jessica Helfand, the author of Design: The Invention of Desire, has done much to promote design discourse. She is a designer, writer and a founding editor of Design Observer, an influential design commentary website, as well as serving on the faculty of the Yale School of Art. “Design is to civilisation as the self is to society,” she avers.

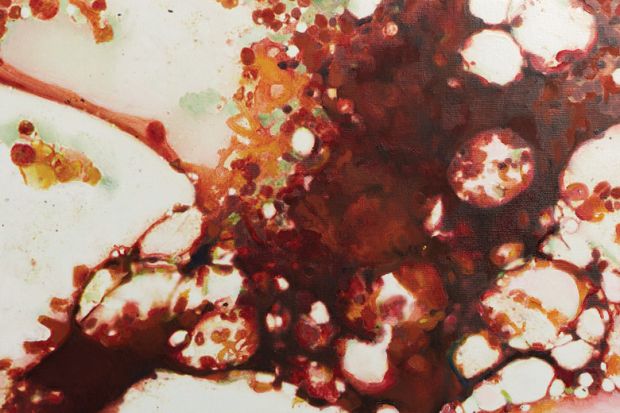

Here, she seeks to illuminate “the soul” in design: “To be human is to struggle with the unknowable. To design is to make things knowable. It is in the ever-widening gulf separating these two polarities that this book locates itself.” The book’s illustrations, abstracted from scientific images of human tissue, are intended to communicate the fact that “it is within the stunning visual vocabulary of biological beauty that we present as a species”. Helfand’s book bridges the universal and the personal; it has no references and is based on her own reflections, opinions and professional judgements.

Short, easy-to-read chapters are named after states of being rather than the qualities we typically attribute to design. Form and function are here replaced with “compassion”, “humility” and “patience”. Design services “our ever-present appetite for fantasy. Because that’s a basic human need too.” Helfand’s examples in her chapter on “Fantasy” range, unexpectedly, from the answerphone to the paste-ups that graphic designers send to printers. Writing about “Authority”, Helfand seems equally disillusioned by tangible markers of identity (passports) and digital ones (social media identities). Her previous book, Scrapbooks: An American History, examined a medium that foregrounds material memories as opposed to the digital memories captured by Facebook. In this new book, relationships between the social, the material and the digital are ever-present. In “virtual spaces there is no irony”, she asserts. Helfand repeatedly critiques social media, from the circulation of selfies to the inadequacy of using Facebook’s “like” button to respond to death notices on the site (a problem now partly solved by its limited range of reactions buttons).

Helfand’s book is informed by the death in 2013 of her husband and collaborator, William Drenttel, from brain cancer, as the chapter “Humility” makes clear. They were a public as well as a private couple, co-founding the design firm Winterhouse and the website Design Observer, and were honoured jointly with the AIGA medal the year that Drenttel died. Her essay on “Compassion” is sceptical about the efficacy of the design consultancy IDEO’s approach to death as a design opportunity, and she instead places her faith in the potential of interdisciplinary encounters between art and medicine, literature and science. In “Melancholy”, she points out that “sadness has to be designed too”, with examples including cemeteries and gravestones. Helfand cautions us that design can do little to assuage mortality. Designers, and others, should resist desire and display humility, she urges. We should pay attention to our moral compasses: “We are people first, purveyors second” and “to embrace design…is to engage humanity”.

Grace Lees-Maffei is reader in design history and programme director for the professional doctorate in heritage, University of Hertfordshire. She is co-editor of Designing Worlds: National Design Histories in an Age of Globalization (2016).

Design: The Invention of Desire

By Jessica Helfand

Yale University Press, 228pp, £16.99

ISBN 9780300205091

Published 7 June 2016