One day in 1981, I passed the friend of a friend in the street and tried to greet her. She studiously ignored me. A couple of weeks later, she appeared to cross the road to avoid me, chin jutting determinedly away.

As far as I knew, I had never been “cut” like this before, so I made enquiries. Apparently Antony Sher was to blame. My acquaintance had been so appalled by the actor’s portrayal of the libidinous lecturer Howard Kirk in the BBC television version of Malcolm Bradbury’s novel The History Man, that she had decided to eschew all persons in academic employment. The university was clearly a moral cesspit.

My non-friend was basically right. The mores of the university were different from those of the town, although less so than they had been: Bradbury’s novel was published in 1975 and so was in essence about the early 1970s, which I think was the peak period for the campus as a den of iniquity. Former policemen of a certain age will tell you that the University of Warwick – where I was a junior lecturer – was then the centre of illegal drug distribution in the area (although the situation changed quite rapidly after that). And there were quite wide academic social circles in which sexual behaviour mirrored that previously seen only among privileged groups such as aristocrats and film stars – and certainly not among academics.

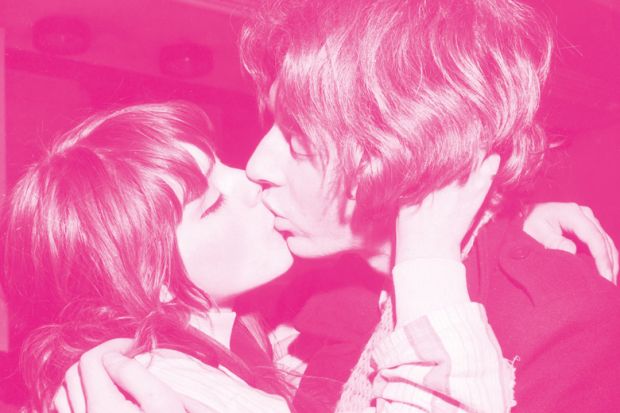

In the terms of a previous generation, there was quite a large and eclectic “fast set”, which you could join simply by turning up in the early evening at a particular bar. An observer could tick off the permutations: staff/student went unremarked, but staff/catering manager was noted, as was retired soldier/sporty student. Young women with regular boyfriends or fiancés (whether on the campus or not) did not seem to think that this precluded their right to “flings”.

It was a revolution in the normal sense of rapid, fundamental change. Only half a decade earlier I had been an undergraduate at a University of Oxford that had still seemed in essence Victorian in its assumptions. You could be “rusticated” from a men’s college for having a woman in your room during proscribed hours, notwithstanding the head porter’s frequent remark that it was possible to have an erection at any time of day. There were rumours that at Lady Margaret Hall – then a women-only college – the bed had to be moved into the corridor if a student entertained a man in her rooms. Cue the same head porter’s remarks on the viability of the floor as an option.

I think we can ignore the worldly cynicism of that former military man and conclude that there was relatively little sex going on in the Oxford of the 1960s. Opportunities were brief and limited. Young women had every reason to fear the consequences in terms of disease and incompetent contraception: these could ruin lives. My guess is that a substantial minority of my contemporaries, if not a majority, graduated as virgins. I acknowledge the theory, expounded mostly in pubs, that nothing really changes: that the amount of sex going on is constant but that people keep quiet about it during puritanical periods and boast and exaggerate when permissiveness is the self-image of the age. But the massive anecdotal evidence, which I inadvertently accumulated, contradicts this theory. Things really did change.

I must acknowledge that I am talking about place as well as time. Warwick – and probably all the new universities of the 1960s, if you judge by the fiction set in them – was a good deal more licentious than older institutions; the atmosphere at Oxford, which I continued to visit regularly, remained much more conservative, as it did at Stanford University in California, where I was a visiting academic. Andrew Davies’ television series, A Very Peculiar Practice, was set in a university health centre based on that of Warwick, and included an episode in which the medical team has to deal with a revived strain of venereal disease, which everyone – including the vice-chancellor – contracts.

If you are the sort of determinist who thinks morals largely follow functional necessity, then this era is easily explicable. Conditions had changed. The Pill was a reliable form of contraception and antibiotics almost eradicated sexually transmitted diseases while massively reducing the harm they did if you were infected. A far more complex factor is the decline of shame. You can also argue that sexual permissiveness had deep intellectual roots, ranging from Freud to the Utilitarians. But, at an immediate level, it was a change in fashion. Leaders of opinion were liberated. Promiscuity and progress went hand in hand, symbolised by the dreaded Howard Kirk.

Naturally, as revolutionaries do, we thought this change was permanent. But conditions changed and so did mores. Venereal diseases fought back against antibiotics and the Pill turned out to be more complex medically than had been blithely assumed. So far as the campus was concerned, the most immediate change was demographic. In the early 1970s, nearly everyone had been under 30, and there were new appointments every year. But from 1976 to 1989 my own department appointed just one person, specifically as “new blood”. So we grew old together: along came the grey hairs and the paunches and the children, and all that libidinous activity seemed crushingly inappropriate – at least to most of us.

Feminism also changed. The first feminists I came across were clear-eyed types who were likely to look you straight in the eye and proposition you because it was their free and equal right to do so. They were largely replaced by women who regarded most sexual activity as highly ambivalent, if not clearly repressive. Libertinism had become conservative, and some conservatives were libertines. I find it an interesting little straw in the wind that, at the end of the final episode of The History Man, there was a caption to the effect that Howard Kirk – previously thought of as a trendy lefty – had voted Conservative in the 1979 general election, which brought Margaret Thatcher to power.

The sexual revolution both widened and narrowed. It widened in so far as the mores of the campus spread to other sectors of society – although I’m not convinced that, in spreading, it retained its cocksure contempt for jealousy. But it also narrowed spiritually, as issues of coercion and appropriateness came to the fore and undermined the idea of the autonomous individual.

The best illustration of this was what happened to homosexuality. It was, of course, de rigueur in the circles in which I moved in the early 1970s to hold that homosexual relations were of equal worth with heterosexual, an evaluation that differed from that made by most of society. Such relations existed overtly, including between staff and students. I remember one distinguished professor bemoaning over a drink that he had no homosexual feelings. In a context that would otherwise have offered him opportunities for a huge variety of experience, his narrowness of taste doomed him to miss out.

The widespread acceptance of homosexuality is one of the more lasting benefits of the sexual revolution. But the change has been complicated. When I was an undergraduate at an overwhelmingly male Oxford of single-sex colleges, homosexuality was the classic elephant in the room, to be muttered and snickered about rather than discussed properly.

There were at least three heads of colleges and numerous fellows whose attempts to seduce male undergraduates were prolific and notorious, but nobody ever complained; it would have seemed very poor form and would also have involved the police, since homosexual acts were not legally permitted until the year I graduated. Yet, despite the widespread acceptance of homosexuality in society now, it would be unthinkable for anyone in a position of academic responsibility to behave as those college heads did in the 1960s.

A similar contrast can be seen in the case of Nicholas Goddard, the University of Manchester professor of chemistry, who was forced to resign earlier this year because of his not very secret acting career in erotic films. When I arrived at Warwick, one English lecturer posed as a Page Three girl and another, Germaine Greer, could be seen revolving her tasselled breasts in opposite directions on a television sketch show called Nice Time. I relished the story told by an undergraduate who watched the show with his father. The latter sat open-mouthed, forcing out the words: “And that is your Shakespeare tutor?” It was all treated as good fun, and showed how far we had moved on from the stuffy milieu of Lucky Jim.

Everything nowadays seems less fun by a huge margin. I used to glory in the relaxed atmosphere of the campus, and in how staff and students socialised together; apart from anything else, I think people learned a lot. Later, it all seemed to become more American, with people worried about grades and coercive relationships. And that brought in the disease of excessive regulation: attempts to rigidly define sexual harassment even though, in reality, the location of its boundary with flirting depends on deep subtleties of the specific interacting personalities.

I am well aware that in making this comparison between past and present I am offering a view that is both personal and specifically male. So I must address the question of what happened to the (fairly) “naughty girls” of the 1970s. I remember that the romantic novelist Barbara Cartland was still around, opining that promiscuous women invariably became “coarse, hardened and bitter”. In my experience, this view is hopelessly wrong. Some of those I knew became among the most successful, happy and generous of people.

But this is mere anecdote and conjecture: someone else can do the research and write the book. Personally, I can be only grateful for having spent a decade as a libertine and four as a family man, living in ways that my father and his father wouldn’t have dreamed of. I will not be joining St Augustine and Malcolm Muggeridge in the ranks of remorseful puritans.

Lincoln Allison is emeritus reader in politics at the University of Warwick and the author of books on subjects including sport, political philosophy and travel.

Ah yes, I remember it well

It is not uncommon to hear male baby boomer academics regretting in the pub after work that their younger colleagues have opted for the gym instead. Such conversations tend to fall back into nostalgia for a lost Golden Age, when nobody was remotely bothered about health advice, when liquid lunches could last several hours, when the sun shone every day – and when sex was freely available whenever, wherever and with whomever.

But the question I ask myself, as a woman of that generation, is whether these visions are anything other than a dream of what might have been had the dreamer not been so busy getting a good degree and climbing the academic ladder. I am absolutely sure that many of those now-distinguished, elderly academics who protest so much about the great time they had in the late 1960s and 1970s were, in reality, much less familiar with sex, drugs and rock’n’roll than they profess to recall.

I am not suggesting that there was no campus sexual revolution compared with what went on in the 1950s, just that memory distorts the past and that things were actually more complex. The Pill undoubtedly did give women more sexual freedom eventually, as did the Abortion Act of 1967, but nothing changes overnight and we were products of a very unliberated upbringing. We all knew girls who had been obliged to marry and drop out of education because they were pregnant, and one of my friends was expelled from her hall of residence in her second year when her pregnancy was discovered.

It was against this background that we endeavoured to engage with the new cultural myths that stressed the importance, nay the necessity, of having unfettered sex. I spent all of my first undergraduate year trying to hide the fact that I hadn’t yet lost my virginity when everyone around me seemed to be enjoying a rampant sex life. Some years later, comparing notes, I discovered that mine was not a unique problem. While we all talked about the great sex we were having, few of us actually had much action at all. My sex life gained ground once I had taken that first unmemorable step with someone whose name I have forgotten, and I embarked on my second year with a feeling of vindication.

For me, as for many of my friends, the revolution was not just about sex: it was about the freedom to challenge our parents’ expectations. We smoked a lot of dope (and, unlike Bill Clinton, did inhale). We went on marches and sit-ins against the wars in Vietnam and Cambodia. We sat around singing protest songs. We ostentatiously remained seated in cinemas when the national anthem was played. We talked a lot about class warfare and some of us admired Mao.

But it was important to be seen to be liberated. I remember wandering around in a full-length semi-transparent flowered gown with only a pair of knickers underneath (I was slimmer in those days). As for the sex – well, in today’s climate, I could probably have claimed sexual assault or even date rape on numerous occasions. But in the cold light of dawn all I asked myself was how I could have been so stupid and how long it would take me to walk home.

There was a lot of what we now call sexual harassment: lecturers who propositioned or groped you; officers of the law who manhandled female protesters more often than they did men; fellow students who made you feel uncool if you didn’t agree to have sex. It never occurred to me that this might not be normal, since a traditional upbringing had programmed women to expect such behaviour from men. A swift slap or kick, an oath or sharp verbal put-down seemed to work as a deterrent most times, although there were always those who repeated their attempts. I find myself astonished by some of the cases that go all the way to court today: a sure sign that the world has changed a lot in 40 years.

So it was hardly surprising that many women were drawn to the emergent women’s liberation movement in the early 1970s. I admired the women who took part in the Miss World protest in 1970 (during which a group of activists stormed the stage at the Royal Albert Hall) and I supported the liberation movement when, in 1977, it added the right to define our own sexuality to its list of demands. Today, I can see that a lot of what we had been taught by our mothers was hypocritical. Despite the overt codes of restrained sexual behaviour, our parents’ generation had experienced a different kind of sexual liberation during the anxious years of war. Perhaps that was why they were so protective of their daughters in the 1950s, and perhaps that is also why my generation reacted by becoming more politicised and determined to shock. Of course, our belief that protesting could bring about world peace was naive, but the movements that began in the 1960s for civil, women’s and gay rights did bring about positive social and legal changes, so all that righteous anger was not totally wasted.

Students today seem more responsible than we were: they smoke less, exercise more and don’t drink and drive as much as we did. But they also seem less laissez-faire than we were, less willing to engage with ideas they don’t agree with, readier to complain through official channels than to take to the streets. Whether their sex lives are truly different from those of earlier generations remains unknown, although I suspect they are not. After all, even in the distant 1930s students seem to have been going at it like rabbits, if we can believe some elderly people’s memoirs. The difference is that the so-called campus sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s was more “in your face”, and part of a much broader social revolution that served to break down some of the gender, class and racial barriers that had stood for generations.

Pill or no Pill, it’s not exactly liberation to end up in bed with someone you don’t fancy, nor to join a commune, as a friend of mine briefly did, only to discover that it was the women who did all the cleaning, cooking and washing-up. A lost Golden Age? As a woman, I don’t think so.

Susan Bassnett is professor of comparative literature at the University of Warwick.

后记

Print headline: Sex and the single scholar