What sort of books inspired you as a child?

I remember, in 1974 or 1975 (my early teens), coming across a small publication called Black Makers of History, written by Sam Morris. It contained brief biographies of historical figures such as Marcus Garvey, Toussaint L’Ouverture, Shaka, Harriet Tubman, Patrice Lumumba, Mary Seacole and Matthew Henson. It was the first time that I learned about such figures, as my schooling made no mention of black history. This booklet had a profound effect on me, and I still have it. In 1981, I received a pocket-sized copy of Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery, an inspirational read that I never tire of returning to.

You started your career as an artist and curator. Which books spurred a shift into the academy?

The writings of Rasheed Araeen, a Pakistan-born, London-based artist and writer, had a major impact on me, as he argued for an art history (and indeed a contemporary art world) that took more respectful account of the contributions of black artists. His collected writings, published as Making Myself Visible in 1984, shaped much of my activities as an exhibition organiser and writer of art criticism from the mid-1980s onwards. In the early 1990s, I developed these interests further by embarking on a PhD at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Your new book, ‘Roots and Culture’, explores the black British cultural efflorescence of the 1980s. Which books proved most helpful for studying this phenomenon?

As artists who emerged in the 1980s, we have had to be our own documenters, commentators and archivists. If we were not writing ourselves, few people, if any, were there to write about us. Paul Gilroy’s book There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack was a major influence, with its powerfully expressed, deeply nuanced considerations of cultural formations and the ways in which the politics of “race” reflected in the lives of so many people in Britain.

Which books from then would you recommend to non-specialists as capturing the flavour of those times?

For historical context, Peter Fryer’s Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. When it came out in the mid-1980s, it enabled me to see the black British presence as a continuum rather than as something that began with my parents’ generation of Caribbean immigrants. I’d also recommend the catalogue for Araeen’s 1989 exhibition, The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain. As Araeen was the first commentator to dwell in any sustained way on the work of a new generation of black artists in Britain, this is especially useful and credible.

What is the last book you gave as a gift, and to whom?

I’m an avid collector (when funds allow) of first editions. A first edition is a very special way of reading a text, especially one that is historically significant. The last book I gave as a gift, to a good friend, was a first edition of the second volume of Marcus Garvey’s Philosophy and Opinions, published in 1925.

What books do you have on your desk waiting to be read?

Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings.

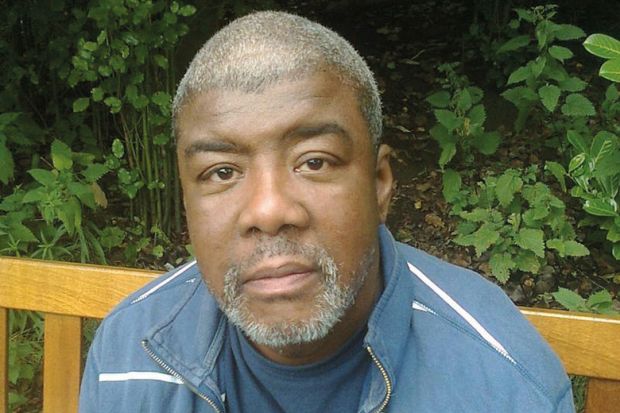

Eddie Chambers is a professor in the department of art and art history at the University of Texas at Austin. His latest book is Roots and Culture: Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain (I. B. Tauris).

后记

Print headline: Shelf life