Did an arithmetic book written by Leonardo of Pisa at the beginning of the 13th century really change the world? Leonardo, commonly known as Fibonacci, a name given to him in the 19th century, is associated with the Fibonacci numbers, whose properties have long fascinated mathematicians. But it was his textbook on calculation, Liber abbaci, that introduced the Hindu-Arabic system of numbers into Western Europe, transforming calculation, facilitating trade and arguably allowing the invention of new mathematical tools that helped to shape the modern financial world.

Keith Devlin is the author of many excellent books on developing mathematical thinking and using video game technology in teaching mathematics as well as more traditional maths topics. He has already written a biography of Leonardo of Pisa: here, he reflects on that project, showing how his fascination with Leonardo developed and how he followed this interest over almost two decades.

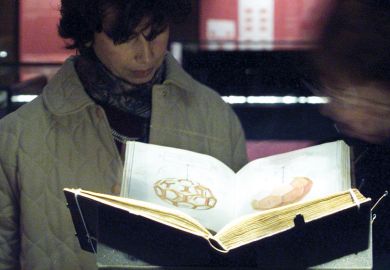

Readers will enjoy this charming account of the inevitable hitches familiar to anyone pursuing historical research: the library closed because of a holiday one didn’t know about, or a manuscript being unexpectedly unavailable. They will admire Devlin’s bravery in seeking access to Italian archives when his limited Italian language skills cannot persuade the custodians of his bona fides, and envy his luck in finding a native English-speaking librarian to smooth the way when his attempt to see a manuscript in Florence seems likely to end in failure. The story of the posthumous publication of Laurence Sigler’s English translation of the Liber abbaci in 2002 is both heartwarming and terrifying, in that the fruit of so much work was so nearly lost because it was stored in an obsolete digital data format.

Devlin makes a strong case for Leonardo’s importance, noting that it was Leonardo’s short vernacular handbook (only recently identified) rather than the massive Liber abbaci that drove the switch to the new number system. I am not convinced that the argument that Leonardo was the Steve Jobs of his day adds much to our understanding of Leonardo and his context, but perhaps I am just the kind of person who dislikes such comparisons.

Finding Fibonacci is sometimes repetitive, and it would have benefited from tighter editing (which might have spotted the assignment of several 20th-century painters to the early 19th century). For me, it makes rather too much of an analogy between manuscripts and photocopies, and it has some other curious features. As if Devlin feels that his story isn’t enough in itself, he offers a fascinating description of his own early struggles with mathematics, and an equally interesting chapter about writing popular mathematics. He also includes extensive material by William N. Goetzmann about Leonardo’s role in the origins of modern finance, through his examples on topics such as interest calculations, present value analysis and currency exchange. Goetzmann’s article is clear and illuminating, but inevitably his style is different from Devlin’s, and the final chapters lack the narrative flow of the first part of the book.

There is much here to enjoy. Devlin’s enthusiasm for his subject is infectious, and this reader, at least, has been inspired to return to Sigler’s translation of Leonardo’s important book.

Tony Mann is director, Greenwich Maths Centre, University of Greenwich.

Finding Fibonacci: The Quest to Rediscover the Forgotten Mathematical Genius Who Changed the World

By Keith Devlin

Princeton University Press, 256pp, £24.95

ISBN 9780691174860

Published 12 April 2017

后记

Print headline: The man behind the sequence