In many ways this is an excellent book. Jeremy Waldron has always written well and argued clearly. The main drawbacks are that he does go on and he strays a lot when one is just dying for him to get to the point. One could extract the bones of this book and put them into a superb long article. Reading it through as a whole evoked for me the experience of a student who once told me that she thought she was bothered a great deal about the issue of abortion, but after reading a book on the subject which argued relentlessly this way and then that, she really didn’t care any more.

It matters too, for practical issues such as “basic equality”, as Waldron calls it, that the subject is not presented as something so imperturbably complicated that perhaps we are not, in the end, sure what it is – as this might be seen as an excuse not to treat our fellow humans with common decency. Of course, one should follow the argument where it leads; but it’s hard to believe that the idea of treating people as having equal value at some fundamental level can be quite as complicated to justify as all that. I was a little puzzled as to why God and religion were dragged into the discussion so often, although Waldron argues that much of the issue may be satisfactorily secularised.

Thankfully, Waldron spends quite a lot of the book talking about Kant. The essential idea here is that a person’s capacity to choose and deliberate over the course of their lives means that to treat someone in a way which does not acknowledge this, is tantamount to treating them as a thing. Thus you should never treat people as a mere means but always also as an end. If you don’t do that, you are not even beginning to treat them in a moral way – even if, one may note, you do them good. Perhaps this minimum is enough to ground the designation of the basic equal worth of persons, and how they consequently shouldn’t be shoved around like bits of furniture.

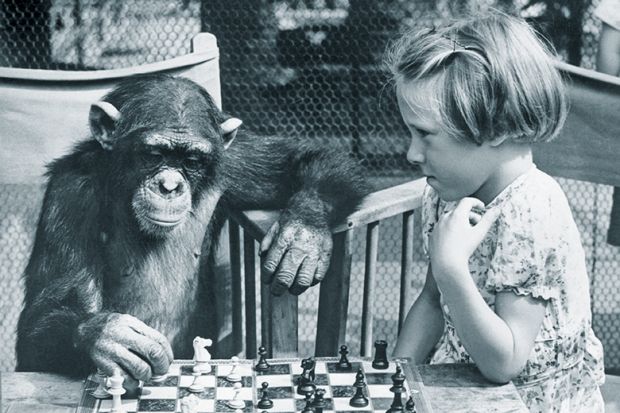

Waldron’s finest chapter is the last. Here he addresses Peter Singer’s argument that if what matters in giving persons all the rights and respect that accrue to persons is their level of cognitive ability (which we adhere to for babies and the profoundly mentally disabled), then all creatures with that level of cognitive ability – for example chimpanzees and dolphins – should be given the same rights and respect. Waldron is at his best when dealing with this, in the end evoking the idea that the difference between a baby or profoundly mentally disabled human being and an animal is the creature’s potential, which in the first case is not yet developed and in the second is tragically compromised. No such considerations apply to a chimpanzee or a dolphin. This certainly points to a difference. The question, as Waldron admits, is whether it is a morally significant difference. But it’s the right place to start the argument.

John Shand is associate lecturer in philosophy at the Open University.

One Another’s Equals: The Basis of Human Equality

By Jeremy Waldron

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 280pp, £23.95

ISBN 9780674659766

Published 29 June 2017