The reignition in England of the row about higher education funding has brought another issue back into focus: how should the cost of teaching different subjects be reflected in the system?

It is no secret that costs vary: teaching a medical degree requires the input of clinicians, expensive equipment and more contact time while classroom-based subjects are cheaper to provide.

However, working out the exact cost is a conundrum that has exercised the brightest minds in university administration for years. After all, it is not just time spent teaching by staff who also do research that needs accounting for (already a fiendish calculation), but how do you reflect the cost of using shared facilities like a classroom (which may not be in the same academic department as the course) or a library, or other more intangible elements?

Initiatives like the Transparent Approach to Costing – which attempts to look at the full economic cost of teaching and research in the UK – have given a broad understanding of how costs are apportioned between teaching and research. The most recent figures suggest teaching international students makes a large surplus; home and European Union students also bring in a surplus, albeit much smaller, and research makes a loss.

But what about the varying cost of teaching different subjects?

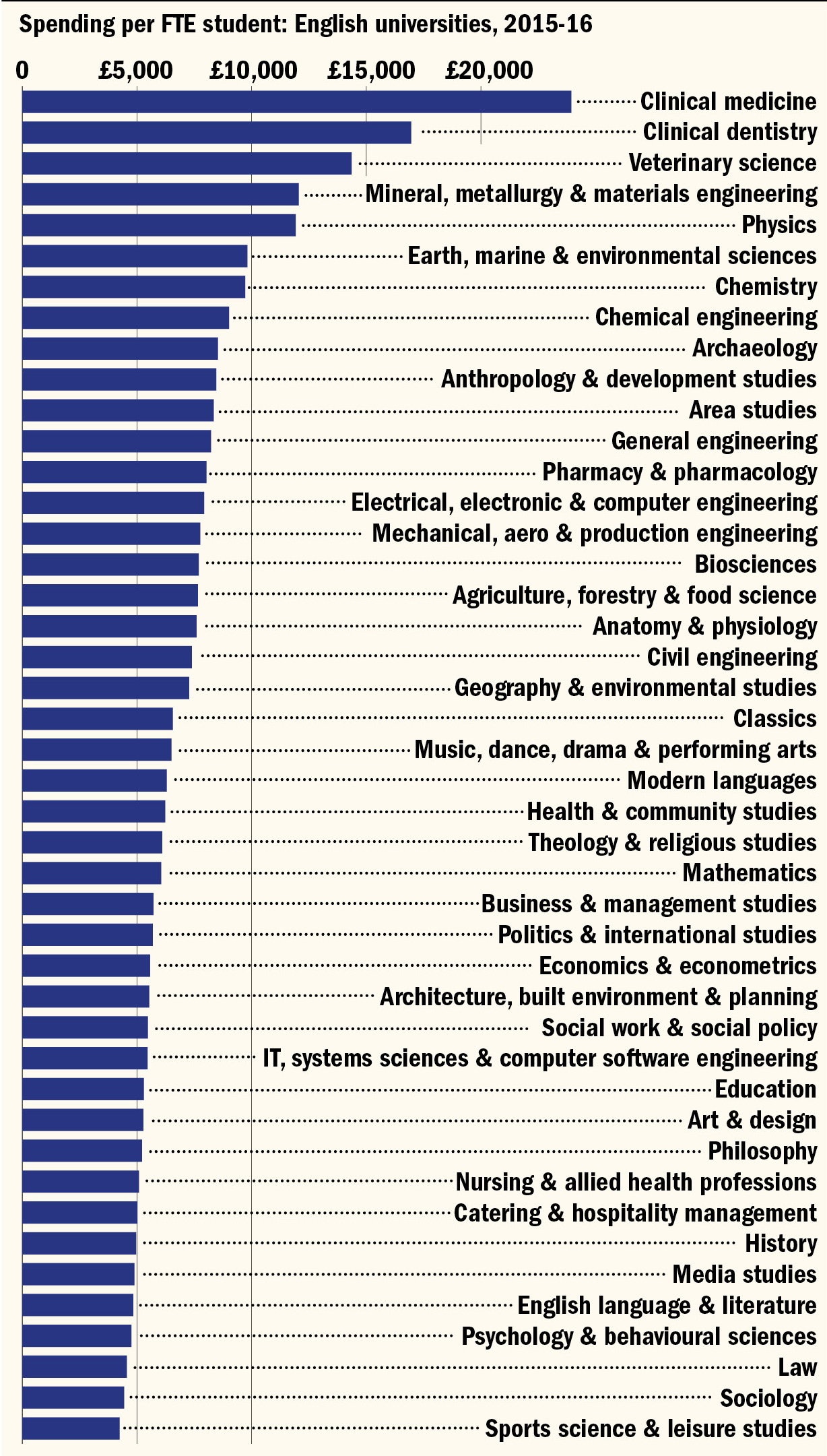

One possible way to gauge this is to look at the data on university spending in each “cost centre” – the nearest proxy there is for an academic department. Dividing this by available figures on the number of students in each cost centre gives what, on first glance, seems to be a plausible approximation of the relative cost of each subject.

According to 2015-16 data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency, clinical medicine departments had, as might be expected, the highest spending per student at almost £24,000, £7,000 above the next highest, dentistry, where costs are almost £17,000 per student.

The other end of the scale contains subjects often in the sights of critics wanting to attack universities: media studies departments spent about £4,900 per student and in sociology the outlay was just above £4,400. But there are also subjects that might be classified as sciences, which are often held up as subjects that should be subsidised – sports science and leisure departments had the lowest spend (£4,200 per student) and psychology and behavioural sciences spent about £4,800.

The lab-based science, engineering and technology fields that are more traditionally thought of as costing more to teach do appear further up the list: chemical engineering departments, for instance, have a spend of just over £9,000 and physics is almost £12,000 but there are also more surprising subjects like archaeology (£8,500 per student). Meanwhile, it is also notable that maths comes lower down the order (£6,100 per student).

Subject specific: course costs per student

In the main the data do give an indication about why there is a current battleground over course cost: there does appear to be a big transfer of funding from students studying classroom subjects to others (and given that the Trac data have shown research makes a large loss, any surpluses will be funding this, too).

Of course, these figures do not present the whole story and can only be a rough approximation. The student numbers include postgraduates, who may in reality cost more to teach, and then there are all the other elements of university spending that many would argue should be funded by fees and taken into account when thinking of the cost of a degree.

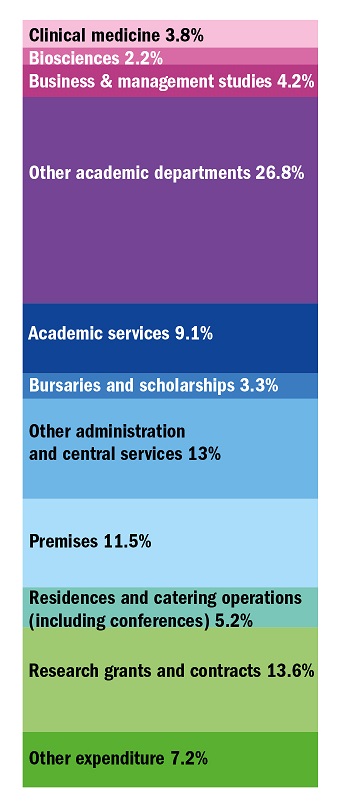

One way to illustrate this last point is to look at how overall university spending is split between departments as well as every other area of activity in higher education.

This shows that about a third of spending in English universities goes through academic departments, with business and management studies taking the largest slice of any one subject at 4.2 per cent of all expenditure and clinical medicine second at 3.8 per cent.

Perhaps more interesting is the amount spent on other activities: administration and central university services take up 16.3 per cent of spending. This includes money spent on bursaries and scholarships (about 3 per cent of total expenditure), showing how a fair chunk of income from fees in effect subsidises students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

But how might all these data – particularly on the costs of provision by subject – affect policy?

The most expensive subjects to teach do still receive some top-up funding from the Higher Education Funding Council for England: £10,000 per student for medicine, dentistry and veterinary science; £1,500 for lab-based science courses and £250 for “intermediate-cost subjects” (although in reality the final amounts are scaled according to Hefce’s budget). These bands also include subjects seen as important for workforce training like nursing or midwifery.

However, as an Institute for Fiscal Studies report found earlier this year, even though they receive no extra funding, other courses disproportionately benefited from the increase in fees to £9,000 because they are so much cheaper to provide.

It is this realisation that is driving much of the current row over funding and one possibility is that the government moves to a system of variable fees based on course cost and potentially other factors such as graduate earnings.

University costs by area

Gill Wyness, a senior lecturer in the economics of education at the UCL Institute of Education, said there might be logic in this approach given that universities were arguably being incentivised at the moment to provide more humanities courses and less science and technology.

But she added that fees reflecting course cost were “probably not a great idea in terms of how that would affect students. You could speculate that the poorer students would end up choosing humanities and the richer students would end up choosing medicine. So I think it is a bad policy from that point of view.”

Similarly, if graduate earnings were used as a guide to variable fees then there would be problems, according to Alan Palmer, head of policy and research at the MillionPlus group of modern universities.

He has written in a submission to the Treasury ahead of the government's Budget this autumn that using graduate earnings in such a way would be a “blunt instrument” given that they were “more about a return to the individual than to the qualification”.

Ultimately though, the debate is not going to disappear any time soon and Dr Wyness predicted there would be a drive to get more accurate data on the course of cost provision, although she stressed it would not be easy.

“I think a lot of universities are thinking about this a lot as nobody knows what the cost of provision is for anything," she said. "That is a big issue.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?