Reina Lewis

Professor of cultural studies, London College of Fashion

My fave read of 2017 was The Power by Naomi Alderman (Viking). Writing about gender, religion, belief and power since her fabulous 2006 debut Disobedience, Alderman’s latest riff on feminist science fiction is a prize-winning page-turner. Global patriarchy is suddenly reversed when first teenage girls, then all women, discover they control electrical volts from their fingertips. Alderman’s riveting account of power gone right and power gone wrong pairs beautifully with the long-awaited arrival of Philip Pullman’s The Book of Dust, Volume One: La Belle Sauvage (Penguin Random House Children’s), which continues the theme of the sinister power of corrupt religious institutions. Alderman, I’ve adored since she started; Pullman, not until my 10-year-old nephew lent me the His Dark Materials trilogy.

Xolela Mangcu

Professor of sociology, University of Cape Town

Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails (Chatto & Windus) is a biographer’s delight. It offers a readable account of some of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century: Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and others. Bakewell shows, among other things, how Sartre took Husserl’s injunction for philosophers “to go to the things themselves” (phenomenology) and applied that concept to the study of human existence (existentialism). The emphasis on lived experience over ideological abstraction followed in the path of American pragmatists such as Charles Peirce, William James and John Dewey, which is why I cannot wait to get my teeth into Hilary Putnam and Ruth Anna Putnam’s Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey (Harvard University Press).

Michael Marinetto

Lecturer in public management, Cardiff University

The first book I read in 2017 was also my favourite read of the year: Stuart Jeffries’ Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School (Verso) – a history of the Institute for Social Research at Goethe University, more popularly known as the Frankfurt School. Jeffries offers an intimate history of “Café Marx”, containing insightful, amusing and, at times, tragic biographical sketches of those maverick Jewish intellectuals (Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Erich Fromm etc), who gave orthodox Marxism a cultural reboot via psychoanalysis. Their time is now. Again. There will hopefully be several literary highlights entering my orbit in 2018. One of these will be Elif Batuman’s The Idiot (Jonathan Cape). This is a campus novel (a narcissistic guilty pleasure) set in the 1990s, a time when email seemed exotic and lecture halls were smartphone-free. It is about a student who mistakes real life for literary narrative – and so will hit those erogenous intertextual zones.

Jaroslav Miller

Rector, Palacký University, Czech Republic

As a historian with long-term experience of communist regimes, I appreciated Timothy Snyder’s new and in many ways alarming book, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (Bodley Head). In my view, the book offers the following message: let us not live under the illusion that freedom and democracy are deeply and forever rooted in the hearts and minds of Europeans, as the post-truth era may herald sweeping change towards tyranny. Edited by Howard Louthan and Graeme Murdock, The New Cambridge History of the Habsburg Monarchy (Cambridge University Press) is a huge and long-awaited work which will (hopefully) be published in 2018. It brings together several dozen experts on the history of the conglomerate of diverse states and territories once known as the Habsburg monarchy. It has already aroused interest among the international community of scholars since the two planned volumes will cover, in comparative perspective, many issues so far not systematically examined by historians.

Robin Feuer Miller

Edytha Macy Gross professor of humanities (and professor of Russian and comparative literature), Brandeis University

Last summer I picked up from a table on my daughter’s front porch Jessamyn West’s The Friendly Persuasion (Harcourt). Idly reading the first page, I became transfixed. This quiet, luminous narrative is both novel and story cycle, not unlike Elizabeth Strout’s popular Olive Kitteridge. West’s sentences linger in the reader’s mind. The chapter “The Vase” gently yet profoundly depicts domestic love and compromise. I am eager to read Masha Gessen’s The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia (Granta), a recipient of the National Book Award this November. Her courage, honesty and versatility amaze, and she once, astonishingly, even read an undergraduate essay that a student of mine sent her out of the blue. Yet topping my list is Philip Davis’ The Transferred Life of George Eliot: The Biography of a Novelist (Oxford University Press). This year I have been listening in my car to Eliot’s novels, frequently sitting in the driveway to finish a chapter, not wanting to leave her company.

Joe Moran

Professor of English and cultural history, Liverpool John Moores University

I enjoyed Brian Dillon’s Essayism (Fitzcarraldo). The ever-interesting Fitzcarraldo Editions are, along with Notting Hill Editions, reviving the book-length essay. Dillon is a sharp and generous guide to this digressive, voice-driven, capacious and very current form. His book is also an eloquent personal essay in its own right, on his own life as a reader, writer and depressive. And while we are on the subject of the essay, one of my favourite current exponents of the genre is Zadie Smith. I am looking forward to her new collection, Feel Free (Hamish Hamilton), out in the new year. Some of these pieces, like a brilliant one published this year about how dancers from Fred Astaire to Beyoncé have inspired her writing, can already be found online, but it will be good to have them all in one place.

Sir Anton Muscatelli

Principal and vice-chancellor, University of Glasgow

I have just read Nicola Pugliese’s Malacqua (And Other Stories), which was published in 1977 but then mysteriously withdrawn from circulation by its author until after his death in 2012. The setting is Naples during four days of incessant rain. There are also supernatural and fantastic episodes that shake the population. Each of the characters’ thoughts appears as a stream of consciousness, as they reflect on their lives: how they are, and how they might like them to be. Jean Tirole won his Nobel prize for his technical and theoretical work on industrial organisation and market power, but his new book, Economics for the Common Good (Princeton University Press), has chapters on the moral limits to the market, the governance and social responsibility of business, and regulation in areas such as digital markets. As someone who feels strongly that the value of economic science lies largely in how it can help formulate public policy, I am looking forward to this contribution by a great economist.

Joanna Newman

Chief executive and secretary general, Association of Commonwealth Universities

I’ve just reread Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights (Scholastic) with my 10-year-old niece before we tackle The Book of Dust, Volume One: La Belle Sauvage. I find it a magical read, awakening her curiosity (and mine) to the spiritual and the scientific at the same time. I’m really looking forward to Sarah Phillips Casteel’s Calypso Jews: Jewishness in the Caribbean Literary Imagination (Columbia University Press), an intertwining of the Jewish and black experience, explored through two major traumatic events: the Sephardic diaspora of the 15th century and the Holocaust. Caribbean fiction compares Jewish persecution with the horrific experience of the Atlantic slave trade. There is also a new work on the refugee experience from Daniel Trilling, Lights in the Distance: Exile and Refuge at the Borders of Europe (Pan Macmillan), that will bring to life the perilous journeys of those at the borders of a Fortress Europe, where generosity is in short supply.

Shane O’Mara

Professor of experimental brain research, Trinity College Dublin

Two very different books, both dealing with human frailty, one intensely personal, the other deliberately universal. I’m greatly looking forward to Maggie O’Farrell’s I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death (Tinder Press), describing her near-death experiences. O’Farrell’s writing has wonderful immediacy and urgency, and her storyteller’s turn as an episodic memoirist looks to be one of the reads of the year. I really enjoyed Robert Sapolsky’s Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst (Bodley Head). He starts with the antecedents of a decision – it doesn’t matter what – and undertakes a journey backwards to examine its causes. This journey takes us from milliseconds before, to seconds, and then further back again, journeying to the weeks and months beforehand. The book widens out, examining us “at our best and worst”. Sobering reading.

Aaron Rosen

Professor of religious thought, Rocky Mountain College, Montana

After 15 years, I left the UK for the US on the day of the Brexit vote (smugly, I must admit, until we elected the Narcissist-in-Chief). Ever since then, I’ve been obsessed with reading books about journeys and transitions as a transparent, self-administered form of therapy. John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley: In Search of America (Penguin) has helped me in my attempt to fall back in love with America. But he also explains better than anyone why that is so difficult. His description of the racism he encounters on his road trip is still hauntingly true today: “Here, I knew, were pain and confusion and all the manic results of bewilderment and fear.” I’m looking forward to reading about a different journey, the Norwegian cartoonist Jason’s graphic novel about walking the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in Spain, On the Camino (Fantagraphics). By foot or car, the road is a good place for thinking.

Morton Schapiro

President, Northwestern University

The second volume of Stephen Kotkin’s biography, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 (Allen Lane), offers a chilling portrait, with amazing new details, of Stalin’s two greatest mass killings – the collectivisation of agriculture and the Great Terror – as well as a day-by-day account of his attempt to keep Hitler as an ally. Apologists for Stalin say his brutality was necessary to meet the threat of Hitler, but then why would he have executed more than 90 per cent of his top generals and officers on obviously faked charges? I look forward to Marian Schwartz’s translation of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s March 1917: The Red Wheel (University of Notre Dame Press), the latest instalment of his multi-volume epic novel. March 1917 focuses on the first revolution of 1917 – the one that overthrew the tsar – and allows us to follow the events from multiple perspectives, none of which has the whole story, while also raising deep questions about morality and historical responsibility.

Helen Sword

Director, Centre for Learning and Research in Higher Education, University of Auckland

“Fog everywhere...Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights.” With this passage from Dickens’ Bleak House, Sir Harold Evans challenges writers to cut through the fog of obfuscating language. But before I immerse myself in Do I Make Myself Clear?: Why Writing Well Matters (Little, Brown), I must finish Philip Pullman’s new novel The Book of Dust, Volume One: La Belle Sauvage (Penguin Random House Children’s), which expands and deepens the Blakean universe that he created in his masterful His Dark Materials trilogy. Here, too, the fog rolls over the Thames; here, too, the floodwaters rise. “But never come there fog too thick,” Sir Harold reminds us, “never come there mud and mire too deep, never come there bureaucratic waffle so gross as to withstand the clean invigorating wind of a sound English sentence.”

Jeremy Till

Head of Central Saint Martins (and pro vice-chancellor research, University of the Arts London)

The most important book I read this year is Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing (Zed Books), by Josh Ryan-Collins, Toby Lloyd and Laurie Macfarlane, together with the New Economics Foundation. The title may sound dry and specialist, but the book engagingly opens up the whole topic of land, and the way its ownership and economy profoundly affect a range of issues from structural inequalities to the housing crisis. Best of all, it proposes alternatives, deploying new economic solutions against the orthodoxies of the market. The book I am most looking forward to is Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (Hamish Hamilton). I am off to India over Christmas, and Roy’s book will help guide me in the complexities of Indian society. It has been a 20-year wait since The God of Small Things , so I am in a high state of anticipation.

Nicholas Till, professor of opera and music theatre, University of Sussex

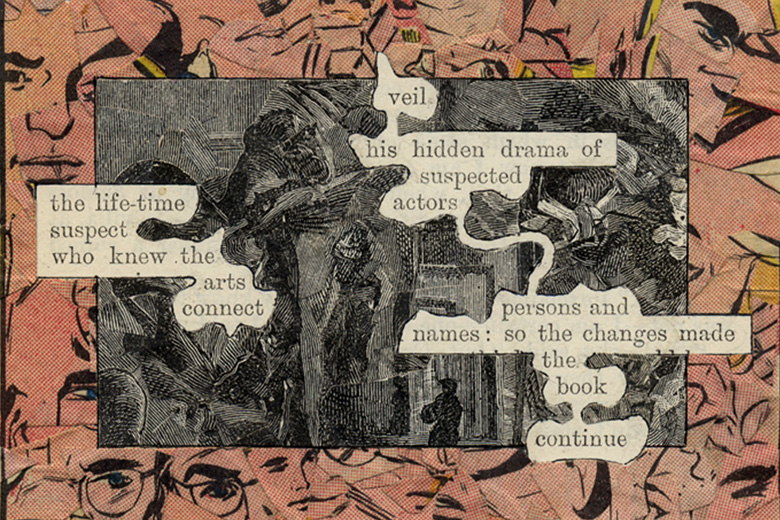

The end of 2016 saw the publication of the sixth, and final, version of Tom Phillips’ art-novel, A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel (Thames & Hudson), 43 years after its first appearance. Working with a copy of a Victorian novel as his canvas, Phillips set about redacting the text to create his own narratives. Take this Virgilian opening, all that’s left from the first page of the original introduction: “I sing a book of the art that was…of mind art…now read on…though I have to hide to reveal.” Each of the 365 pages is a serendipitous verbal puzzle and a work of inventive visual art. Richard F. Thomas teaches a Bob Dylan course at Harvard, where he is professor of Classics, and has now written Why Dylan Matters (William Collins). Academic Dylanologists are legion, and the stakes have been raised since Dylan’s award of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature; I’m intrigued to find out how Thomas argues his case for Dylan as a classicist.

Shearer West

President and vice-chancellor, University of Nottingham

I am enjoying working my way through the Man Booker Prize nominees. I was riveted by Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves (Weidenfeld and Nicolson), which has a unique and complex protagonist, a plot that veers between the casual and the shocking, and a kinaesthetic power in her descriptions of the rural Minnesota setting. Ali Smith’s Autumn (Penguin) exemplifies her usual sharp wit, but the beauty of the book is that it contains the best encapsulation of the Brexit zeitgeist I have read anywhere. I would be remiss not to mention my colleague, Jon McGregor, who was longlisted for Reservoir 13 (Fourth Estate), a taut and elegiac, almost Marvellian, rumination on the impact of a missing child on a Peak District community. From fiction to fact, Paul Greatrix’s True Crime on Campus (University of Nottingham) is a good stocking filler, and the profits will be donated to the Nottingham Children’s Brain Cancer Research Centre.

David Wheeler

Chairman of the International Higher Education Group and former vice-chancellor of Cape Breton University, Nova Scotia

Anyone who enjoys tales of ocean adventure, political influence peddling and corruption in business will be delighted by William M. Fowler’s Steam Titans: Cunard, Collins, and the Epic Battle for Commerce on the North Atlantic (Bloomsbury). Two mercantile entrepreneurs drove the transition from sail to steam power in the middle years of the 19th century, servicing the rapidly increasing transatlantic trading needs of the industrial revolution. Both made their case for government subsidies on the somewhat spurious grounds of naval warfare threats – in addition to guaranteeing mail deliveries. Following the theme of transatlantic triumphs and disasters, Rebecca Fraser’s The Mayflower: The Families, the Voyage, and the Founding of America (St Martin’s Press) arrived well in time for the quadricentenary of the inauguration of what is perhaps the most existentially divided nation in the world. Let us not forget the outrageous acts of larceny and genocide perpetrated on indigenous peoples that accompanied the settling of North America.