We have made significant progress in education in recent years but can only build a brighter future for all by addressing the major skills problem facing the UK.

Tackling this problem is not just central to closing the country’s skills gaps and boosting productivity but is crucial to tackling the issue of social justice.

In England, more than a third of workers do not hold suitable qualifications for the jobs that they do. About nine million of all working-age adults in England and a third of 16- to 19-year-olds have low basic skills. At the same time, employers are crying out for skills in a whole range of sectors, from electricity, gas and water to construction, transport and manufacturing.

With the emergence of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and the forecast that 28 per cent of jobs taken by 16- to 24-year-olds could be at risk of automation by the 2030s, it is clear that our efforts need to be redoubled to ensure that young people are prepared for the future world of work.

While the lack of skills in society ultimately touches us all, the most disadvantaged individuals pay the highest price. They have the most to gain from skilling their way out of deprivation, but are the least likely to do so. Today, millions of disadvantaged children are on a collision course with failure. When just 33 per cent of pupils on free school meals get five good GCSEs, compared with 61 per cent of their better-off peers, too many young people are being set up to fail.

Without a solid nucleus of skills, it is hard to thrive in the jobs market. Instead, the most likely outcome for these individuals is a grim concoction of wage stagnation, fading hope and inertia.

This can change but it requires a skills revolution, which must begin by transforming the way that we view education.

It is customary to talk about building “parity of esteem” between technical and academic education.

But “parity of esteem” only serves to reinforce the divide. The two branches should be intertwined, as parts of the same system of self-improvement, and equally well supported. Education should also be a continuum of learning. This should mean our young people being able to hop on a train line with a series of academic and technical stops, but with the system engineered to provide seamless opportunities to jump back on and travel to other stations when the individual wants to build credits and reskill or upskill.

In England, we are obsessed with university and the idea of a full academic degrees.

Unsurprisingly, this has created a higher education system that overwhelmingly favours academic degrees, while intermediate and higher technical offerings are tiny by comparison. This system is unfit for modern needs.

Our labour market does not need an ever-growing supply of academic degrees. Between a fifth and a third of our graduates take non-graduate jobs. Even the much-vaunted claims to a “graduate premium” start to look shaky when the premium varies wildly according to subject and institution. For many, the returns are paltry.

But this provides us with an enormous opportunity to rebalance higher education, with funding redirected towards courses and degrees that have a technical focus.

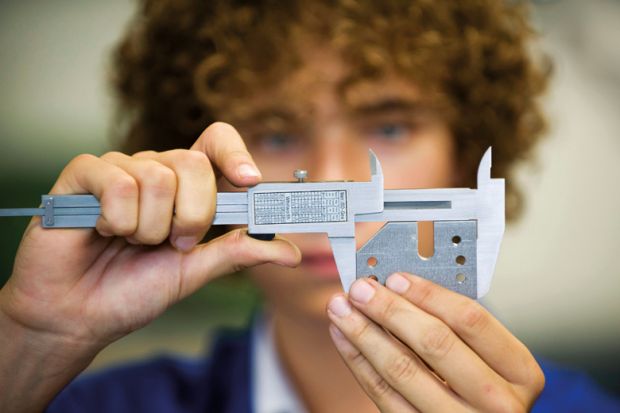

Degree apprenticeships are a great example of how to blend technical and academic learning – and they could be the crown jewel in a revamped technical offering. Students earn as they learn, they do not incur mountains of debt, and they get good-quality jobs at the end. They also help us to meet our skills deficit, so they benefit society too.

Currently there are, however, just 11,600 degree apprenticeships available. More universities should be offering these apprenticeships and I hope that, one day, half of all university students will be doing them. One way for the government to incentivise their growth would be to ring-fence some of the enormous public subsidy that still goes to universities, so that universities can only draw down on this protected funding stream if they offer degree apprenticeships.

When students are paying tuition fees and taking on significant debts, it is vital that they are able to make informed choices about their courses – that means being transparent about the return that degree courses will bring.

Some Russell Group universities may be highly ranked for their research but flounder on teaching quality and employability. We should move to a system that confers prestige on universities, such as Portsmouth and Aston, that boost students’ career prospects and earnings. Universities fulfilling these objectives are powerful engines for social mobility, put rocket boosters on the life chances of those who may otherwise have stagnated, and deserve to take the plaudits.

To build a continuum of learning, it must be made easy for people to learn flexibly throughout their lives. For those who are not able to build high-value skills the first time around, or whose skills have been wiped out by a fast-changing labour market, it is important that our system offers a way back. As The Open University’s model clearly demonstrates, flexible learning can be a powerful vehicle for social justice.

Given its importance to continuing learning, the sector should be protected and, as a first step, the part-time premium element of the Higher Education Funding Council’s Widening Participation funding allocation should be ring-fenced.

It is also vital that we create clear routes from further education into higher education. These could be supported through “Next Step” loans for individual higher education modules.

Skills are a social justice issue. By fostering a continuum of learning, by breaking down the division between vocational and higher education, and by focusing on technical training and skills, we can ensure that all, including the disadvantaged, climb the ladder of educational opportunity and into high-skilled employment.

Robert Halfon is chair of the House of Commons Education Select Committee and Conservative MP for Harlow. This blog is based on a speech given by Mr Halfon at the Centre for Social Justice on 5 February.