‘We must tell the public: we promise to cut down the jargon and up our literary game if you show patience with us and with each other’

It takes a long time to do history. In the US, graduate students spend an average of three to four years researching and writing their dissertations, the longest stretch in the humanities. After the PhD, a book can take a decade to complete, if you are quick.

The knowledge gained from these marathons often cautions against rash actions and overconfident charging ahead. History books should arrive with a lengthy list of warnings, such as: “this policy has been tried unsuccessfully before”, or “people with good intentions may inflict suffering on others”, or “wars can create as many problems as they solve”. History is slow and painstaking in the making – historians extract evidence from musty tomes in dribbles and drops – and its conclusions often recommend slowing down, thinking plans through and checking first impulses. This runs counter to the light-speed information gush of news cycles and Twitter storms; it is not surprising that history is currently out of fashion.

Over the past decade, many history departments across the US have seen their enrolments decline and their major numbers fall by half. In my department, true to our inclinations, we reacted to this trend slowly. History degrees have been on the decline in relation to all degrees in US higher education for some time, and major numbers have chased the fortunes of the US economy since the 1980s. Following the Great Recession of 2008‑09, we expected a downswing, and that duly transpired. What could we do to reverse global economic trends and widespread student population shifts to science, engineering and business? Plus, national percentages do not address local conditions, and our university required that all undergraduates take a history course.

Our postgraduate programme seemed in much more dire straits, with students averaging eight years to the doctorate and then struggling to find academic positions afterwards.

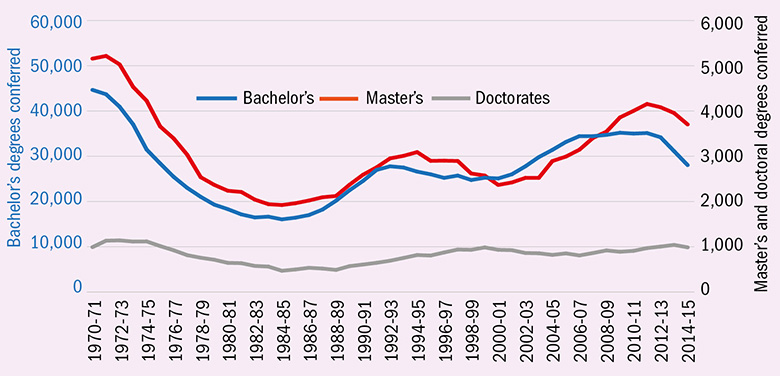

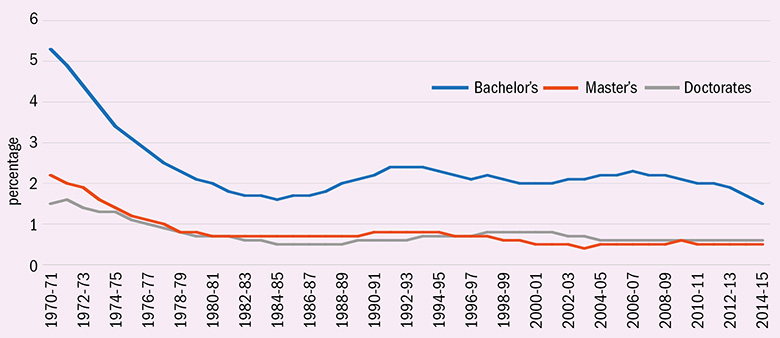

While the number of undergraduate history degrees awarded fell across the US between 1970 and 2015, Department of Education data reveal that the total number of doctorates conferred has held steadier. Indeed, one of the ways by which history departments maintained their profiles as their major numbers sank was to pin their reputations to their postgraduate programmes. But this strategy exposed departments to a statistical pincer movement. Fewer undergraduates meant fewer job openings for PhDs. In November 2017, the American Historical Association reported a decline in the number of jobs being advertised in history for the fifth straight year.

American studies: history degrees conferred in the US

Waning appetites: history degrees in the US as a proportion of all degrees

Accordingly, we at Notre Dame reformed our graduate programme two years ago to hasten time to degree and began to prepare our students to wield history not only in the lecture theatre, as tenure-track professors, but also in the school classroom and the boardroom, as well as in higher education administrative posts such as admissions and undergraduate support. But then, last autumn, the university reformed its undergraduate curriculum, allowing students to choose between a history and a social science course. We received a visit from the dean and were told that we needed to confront our numbers.

So, like many history departments across the country, we are clarifying our purpose and refurbishing our brand. We launched a new history minor, and we are retooling the major to better reflect our global reach and our new clusters of expertise in areas such as the history of capitalism and comparative world empires. The future may not be bright, but I am certain that it will be filled with wild-eyed historians gathered in such clusters, ready to ambush engineering majors with the latest humanities job outcome data.

We are eager to innovate and improve: to think forward and anticipate what the practice of history will look like in the decades to come. But we must hold true to the slowness that has sustained us over the years. When it works best, history is a drag. It forces us to pump the brakes and ask questions, such as “when did that monument to the Confederacy appear in the park?” (long after the Civil War, during the Jim Crow segregation era) and “why does the stone soldier look like the Union infantryman celebrating the North’s sacrifice in the town across the state line?” (because the same manufacturer based in the North provided statues for both Northern and Southern remembrance).

History offers perspectives that minimise the impact of collisions. The US needs this safety feature now more than ever, and we must do a better job of promulgating it. We take our own sweet time reading books, sifting through piles of documents and designing footnotes to show our data trails. We often disagree and revise our interpretations, but we hold one another to the highest standards of evidence and argumentation. This produces articles and books that sometimes come off as ivory-tower obscure. Yet, for all our maddening quirks, we historians know the depth of time. We know that fashions change and that tides that roll out eventually roll back in. It’s incumbent upon us to be patient and endure, to analyse claims instead of swallowing every line whole, and to remember yesterday in the rush to tomorrow.

But we need a new bargain with the public. We must say to them: “We promise to cut down the jargon and up our literary game if you show patience with us and with each other. And please send us your children to major in history. A computer science or finance degree might help you to buy a Mercedes quicker, but a sports car without brakes is a rocket to nowhere.”

Jon T. Coleman is a professor and chair of the history department at the University of Notre Dame.

‘Academics have become resigned to a growing gulf between the way the subject is taught in secondary and higher education’

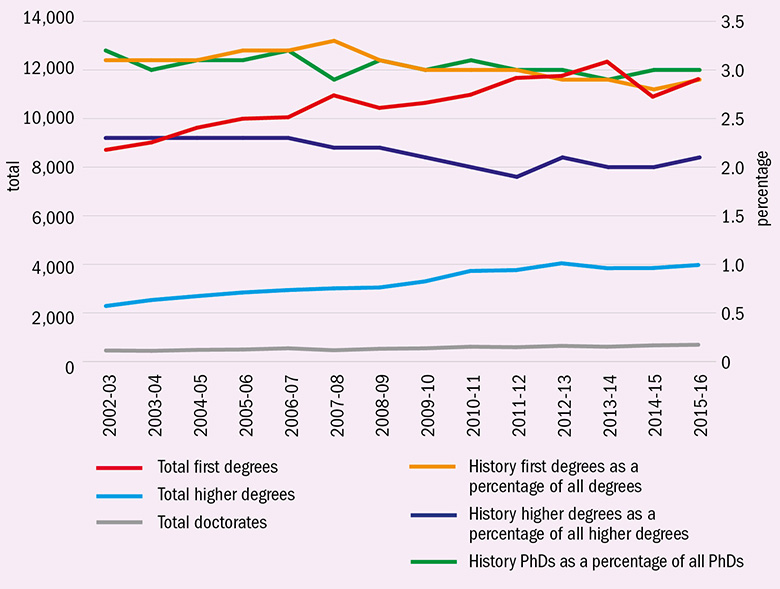

History marches on. In the UK, the subject accounts for about 3 per cent of all undergraduate degrees: only slightly below the 3 to 4 per cent levels that it maintained in the late 1960s and 1970s, before the leap to mass higher education. This is remarkable given the much wider array of modern students’ backgrounds and attainments, and the much wider portfolio of subjects that they study.

History was never as central to the British university curriculum as the golden-age nostalgists imagine, but nor has it been hit so badly by a rising tide of utilitarianism and vocationalism as the hard-bitten Cassandras suggest. The government may be pushing students to focus on their future incomes when selecting courses, but if you control for background and prior attainment, history provides pretty much median graduate earnings – which are themselves still substantially better than non-graduate earnings. (It is not widely noticed, but it is true of most subjects that they end up paying the salaries you would expect given the backgrounds of those who study them.)

Lying behind the steady demand for undergraduate history has been a growing uptake of the subject at secondary school. History used to lag well behind geography in the scrap to be the preferred humanities subject in school exams, but in recent years it has surged ahead.

Sadly, however, former education secretary Michael Gove’s much-vaunted reform of school exams has not changed the nature of pre-university history, and academics have become resigned to a growing gulf between the way the subject is taught in secondary and higher education. In schools, it is still dominated by kings and queens, battles and treaties – even if the kings and queens are now interspersed with military dictators and party chairmen, and the wars are cold as well as hot.

GCSEs, taken at age 16, now demand a wider geographical and chronological range: it is no longer possible to do nothing but 20th-century history. But A levels, taken at age 18, remain as drab as they have been for decades. Only thin shafts of the kinds of economic, labour and social history taught in universities since the 1960s penetrate their curricula. There are rarely even token appearances of gender, race, sexuality, consumption, the body, everyday life, emotions, material culture or the built and natural environments. As for the history of the non-Western world before the 20th century, it impinges only when the West “discovers” or “conquers” it. A brave attempt by one A-level exam board to introduce pre-colonial African history has met with near universal indifference.

In that last respect, departments of history in UK universities are still straining to catch up with their own self-image as global and cosmopolitan. A study by Luke Clossey and Nick Guyatt in 2013 showed that a greater proportion of staff in UK departments specialise in their own country’s history than do academics in the US and Canada. Moreover, only 13 per cent of UK historians specialise in the histories of Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America: about half the proportion found in the US. To judge from an unscientific scan of job ads, progress has been made since, but there is surely a long way to go. That brave A-level exam board had a hard time finding a single pre-colonial African historian in the UK able to help it design its syllabus.

The relatively buoyant state of the undergraduate market should allow for optimism about UK departments’ ability to make further strides in this direction over time. However, there remain some structural obstacles that affect history along with many other humanities subjects. One is the determination of the government and some pundits to steer students into science, technology, engineering and mathematical subjects, even though there is no obviously growing demand for narrowly defined STEM skills, nor any greater graduate premium, properly measured.

Another obstacle is the removal of the cap on student numbers, which has led Russell Group universities to poach students from institutions lower in the hierarchy. This could cause short-termist managers in those lower-ranked universities to look askance at their history programmes’ viability.

Finally, there is the growing trend for hiring junior academics on precarious contracts. It is fair to say that we do not yet fully understand this phenomenon. The number of people pursuing doctorates in history continues to rise rapidly, far outstripping the expansion in the number of jobs available; history PhDs are clearly being used for careers other than academic ones. Often, indeed, they are being pursued for simple enrichment; studying history does seem to contribute to the gaiety of nations, whatever discouragements contemporary fads and fashions seek to throw in its way. But the fear remains that giving early career academics so little incentive to remain in the profession will ultimately cut off the future of the discipline at its roots.

Peter Mandler is professor of modern history at the University of Cambridge and Bailey lecturer in history at Gonville and Caius College. From 2012 to 2016, he was president of the Royal Historical Society.

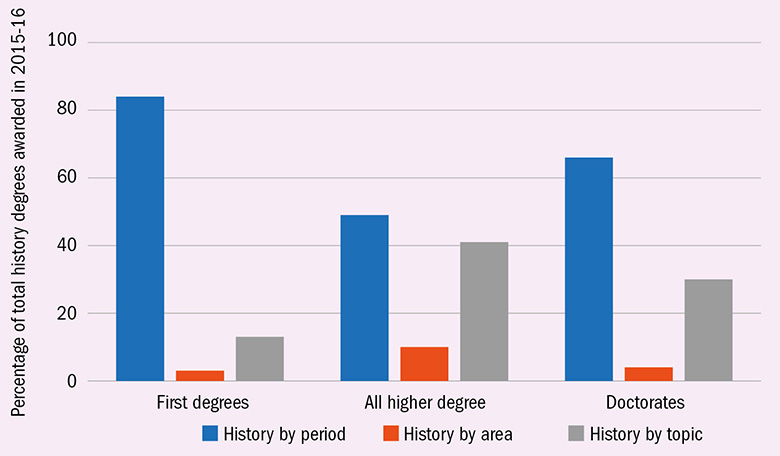

Time is of the essence: trends for history degrees in the UK

Breakdown of UK history degrees awarded

Trends in UK student numbers

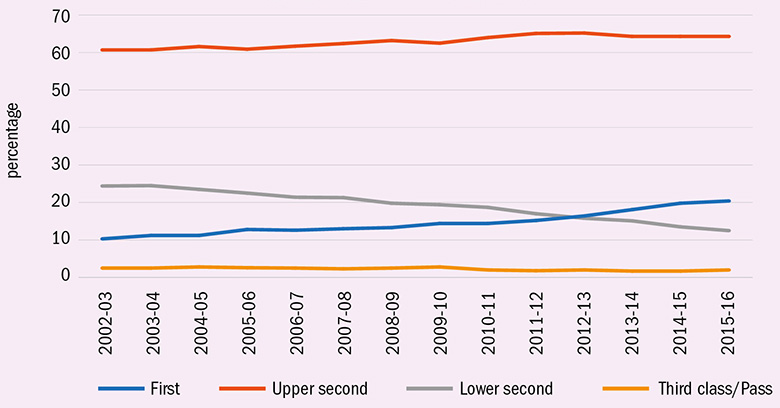

Trends in UK first degree classifications

‘The empty pursuit of “excellence” encourages a narcissistic focus on ticking boxes that enhance careers rather than change the world’

I love it when people ask me what I do for a living: “historian” is always well received.

Most people will recall a history lesson from school or even refer me to a close relative who apparently “loves history”, intimating that such armchair historians might offer some helpful tips on my next project.

Those who are generally suspicious of the humanities tend to look more kindly on history. “I think history is a science,” one politician told me recently, evidently implying a flattering contrast between history and other, woollier, humanities disciplines.

Even attacks on the discipline reveal its importance. Australia’s gaggle of persistent culture warriors believe that “history really matters” and so go to significant lengths to show that we are teaching it wrongly. These bastions of the intellectual right are not preoccupied with whether geography, for instance, is still teaching flags and capital cities, but are concerned that if historians have somehow forgotten about ancient Greek democracy or the achievements of the British Empire, this might mean the end of civilisation in the present, too.

Anyone can see that despite some hopeful pockets of change, history is still clinging, almost pitifully, to the well-trodden study of Western civilisation. Don’t get me wrong: I think we should teach this stuff, because understanding the structures of the world we live in could help us build a better one. The same logic, though, says that histories of sexuality, migration and non-Western regions are also important and timely. And I can’t imagine why a single Australian would suggest that understanding our Indigenous heritage is anything less than the responsibility and privilege of every citizen.

But despite this significant diversity in what historians teach and research, as a discipline we remain wedded to a very narrow conception of Western civilisation in the way that we value the performance of history. I attribute this seemingly intractable problem not only to the discipline itself but also to our education systems.

No one likes an academic historian who criticises history in schools, and I have deep admiration for school history teachers, whose job seems unimaginably hard. But a system where both the teacher’s expertise and the student’s learning are reduced to a centrally regulated tick-box is hardly one likely to encourage thinking outside those boxes.

Although we have much more freedom as history researchers, universities are little better. The empty pursuit of “excellence”, marked by meaningless ranking systems, encourages a narcissistic focus on ticking boxes that enhance careers rather than change the world. Laudable concepts such as “engagement” and “impact” often boil down in practice to cynical calculations about how a project can gain research funding, rather than truly examining the diverse benefits that historians have on the world.

But the main problem is not so much the boxes as the values against which they align. These are without exception grounded in education traditions that privilege the attributes of certain staff – and by extension, students. Growing up with books on the shelf, experience of cultural institutions and regular dinner-table debates always seem to offer a decided advantage in history.

This class-based advantage is also Western. History is grounded in Western knowledge traditions, and these ways of knowing and communicating – the structure of narrative, the logic of persuasion, the types of evidence and the high levels of written English expression – are so valued by the discipline that other forms of knowledge and ways of knowing are pushed out.

I recently spoke to a history teacher in the Aboriginal community of Menindee, who expressed frustration over this. The local Barkindji children, he explained, grow up with a deep, detailed and lived understanding of Aboriginal history and culture. But even in the school subject of Aboriginal studies, the system, he felt, was slanted towards the success of private school girls on Sydney’s wealthy north shore; Barkindji children’s knowledge of the same subject matter was not valued in the same way.

Historians may seek to “decolonise” history in our research, and we may even teach the key texts on decolonisation in our classes. But the structure of history continues not only to value Western civilisation in its subject matter, but also to privilege being a middle-class Westerner.

Perhaps the goodwill granted to us, as historians, is a problem – maybe we tick too many comforting boxes, aligning to things we ought instead to unsettle.

Hannah Forsyth is a lecturer in history at the Australian Catholic University.

‘Enrolments are on the decline, but those students who now elect to study the subject do so for reasons that validate the discipline itself’

The study of history in Canada has undergone fundamental changes since I began my career more than 30 years ago. Once a popular core discipline in the humanities, history has witnessed declines in both its undergraduate enrolment numbers and its coherence as a discipline. It has been partly reduced to a segmented study of other highly specialised but often vaguely defined areas that rely on social science methods and certain ideological assumptions, such as transnational, diaspora or gender studies.

Consequently, history is now spread among many departments, interdisciplinary programmes and even faculties. This has often proved a positive change, bringing varied methods and perspectives to the study of the past, and amplifying voices that for too long were silent or suppressed in historical discourse. But it has made identifying historians increasingly challenging.

Because securing reliable national statistics on history enrolments in Canada would be very difficult, let me use my own institution, the University of Toronto, as a source of some anecdotal evidence. As the largest and most respected school of history in the country, we currently have almost 7,000 separate course enrolments, from students who take just one half-course to specialists and majors. Although still respectable, this total reflects a long decline that parallels the flight of students from the humanities into other more “practical” subjects, a phenomenon seen in many other academic jurisdictions.

The causes are complex. One is no doubt a fear of unemployment or underemployment after graduation in a highly competitive world: a fear stoked by the popular press, governments and parents exercising the tyranny of the dinner table. Another is a belief in a technologically driven future to which only science, technology, engineering and mathematics graduates will be able to contribute effectively – and who, as a result, will reap greater rewards. Previously, history graduates always enjoyed the option of careers in law, teaching and the Civil Service; but over the past decades an oversupply of lawyers has been trained, teaching positions in history have all but disappeared and government employment has not grown in tandem with the number of graduates.

Furthermore, the demographics of the student body have played a role. Toronto is one of the world’s most diverse cities, and the university reflects that diversity. Many historians hired decades ago qualified in an age when European history dominated the curriculum. Despite very active recruitment efforts and aggressive faculty renewal plans, this legacy remains – I am part of it – while our students are looking for areas of study that speak more directly to their experience. Then there is the issue of language. A great many students were born outside Canada, so they approach English to some extent as a second language. Many feel challenged by the sophisticated written prose style and difficult sources of historical research; they find the universal technical language of STEM subjects more accessible.

What I find most hopeful, indeed exciting, about my present students is that their diversity brings a very engaged and broader discussion to the classroom. Moreover, substantial numbers of students choose the European history that I teach because they recognise a need to understand the institutions and experience of the nation that they now call home; and I hear constantly that they want that rigorous command of language and research that history demands. So those students who now elect to study the subject do so for reasons that validate the discipline itself.

And despite the gentle decline in undergraduate enrolments, applications for postgraduate study have held up, representing a splendid pool of exceptional talent. Thus, a great many extremely ambitious and able young people continue to see history as a way of mastering the skills required to become articulate, engaged citizens and critical voices in their society. In a world threatened by populism, fake news and alternative facts, knowledge of history still remains a principal instrument to expose sophistry, malice and misrepresentation.

Kenneth Bartlett is professor of history at the University of Toronto.

‘It is no use historians talking only to other historians while the intellectual traffic of the rest of the world passes us by’

Last summer, as the media followed far-right rallies and their political fallout in the US, medieval studies had its own white supremacy scandal. In a blog post, Dorothy Kim, an assistant professor of English at Vassar College in upstate New York, urged fellow medievalists (particularly white academics) to make a clear stand against such viewpoints. In response, Rachel Fulton Brown, an associate professor of history at the University of Chicago, responded with a blog post of her own, in which she denied that medieval studies had a race problem and denigrated Kim’s scholarship.

Both posts would probably have been read and discussed only by the small number of scholars who are both medievalists and regular users of social media if Brown had not tagged alt-right media personality Milo Yiannopoulos in one of her Facebook posts, resulting in his website publishing an article that lambasted Kim and praised Brown. As Yiannopoulos has 2.3 million Facebook followers, this unsurprisingly resulted in a storm of online attention – much of it virulent – for Kim, and for the scholars who supported her.

Many historians have remained blithely unaware of this incident, and a number of those who have belatedly learned about it have been dismissive of its significance, discounting it as a “Twitter drama”. Even leaving aside the fact that alt-right trolls are well known for posting private and identifying information about the targets of their fury, making their threats potentially a lot more than mere words, this episode signals the key role that social media are going to have in shaping the future of history as a discipline.

Yiannopoulos’ website praised Brown for providing her readers with “facts” and called Kim a “fake scholar”. As the journalist Oliver Burkeman recently argued, online discourse is increasingly polarised: people who are “otherwise sane…adopt, then feel obliged to fight for, the sort of black-and-white, nuance-free stances they’d never defend in calm conversation over cups of tea offline”. Partly this is caused by what psychologists call “in-group bias”, a theory that long predates the internet and refers to humans’ innate tendency to bond within groups and then respond to people outside the group with hostility. However, this age-old problem is intensified online because of social media’s widely discussed “filter bubble” effect, where users end up in intellectual culs-de-sac produced by search engine algorithms.

Academics, of course, often live in their own version of the filter bubble. While the senior common room can be a place of lively intellectual discourse, it can be easy for us to ignore the world outside it. For many historians, social media channels seem like terrible places to attempt to have the kind of nuanced, reflective discussions that our discipline requires. It is becoming increasingly urgent for us to make that attempt, however, and the Kim-Brown clash is a perfect illustration of why.

At a time when white supremacy is making a political comeback, medieval historians cannot ignore the clear evidence that modern fascists – as they did in the 1930s – are co-opting medieval history (particularly of the Vikings and the Crusades) to propagate racist discourse of a glorious white European past. While these extremists currently remain fringe groups, the mainstream perception of the Middle Ages remains one of a white, Christian world: a Game of Thrones universe without dragons but with just as much rape. With far greater social reach than at any previous time, historians now have an opportunity to connect with this wider public and demonstrate the ways in which our past is more complicated, and more rich, than they might think.

Our ability as historians to rebut simplistic misconceptions depends on the availability of both information and personnel. Open-access scholarship is vital to combat “fake news”, not merely in the formal sense of articles being freely available online but also in the form of scholars disseminating their learning outside journals.

Unfortunately, many of the academics most interested in connecting with the public and in producing the kind of history that combats stereotypes are also the scholars most vulnerable to being cut off from the resources that will allow them to publish that research. As an early career scholar on a fixed-term contract, the irony of this strikes me quite keenly. It is my book, published by a reputable academic press four years ago, that got me my current job. But my blog is read by thousands more people than have ever read that book, and it is via online connections over the past few years – meeting potential research partners on Twitter, planning conferences via Skype – that I have made my most dynamic developments as a historian.

It may well be impossible to change the minds of racist zealots, whose commitment to their cause means that they can dismiss the work of scholars such as Kim as “fake news”. But if racist misinterpretations of history are left unchallenged, the mainstream public may find that the search results for terms such as “Vikings” and “the Crusades” will be dominated by alt-right websites. Filter bubbles, after all, expand to incorporate new members, and white supremacists have a vested interest in changing the terms of broader public conversation about the past.

It is no use historians talking only to other historians while the intellectual traffic of the rest of the world passes us by; that risks our becoming history at a time when our understanding of the past has never been needed more.

Rachel Moss is a lecturer in late medieval history at the University of Oxford.

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?