Browse the full list of institutions in this year’s rankings

Kyoto University and The University of Tokyo have jointly topped the Times Higher Education Japan University Rankings 2018.

Kyoto has jumped from third to joint first place to join Tokyo, which topped the first edition of the student-focused rankings last year. Kyoto’s rise comes at the expense of Tohoku University, which has dropped from second to third place in the table.

Kyoto’s performance under the environment pillar of the methodology improved this year. This includes metrics on the share of international students and staff at each institution as well as two new indicators: the number of students in international exchange programmes, and the number of courses taught in a language other than Japanese.

The university also achieved slightly higher scores for outcomes, which measures academic and employer reputation, and resources, which looks at income, staff-to-student ratio, research output, research grants and the national mock university exam scores received by institutions’ entrants.

Japan’s four other National Seven Universities – Nagoya University, Osaka University, Kyushu University and Hokkaido University – also feature at the top of the table between fifth and eighth place. The Tokyo Institute of Technology is again the only institution outside this elite group to make the top eight, in fourth place.

Keio University is the country’s top private university and the only private institution to make the top 10 of the THE Japan University Rankings, which is produced in partnership with Japanese education company Benesse.

The University of Tokyo achieves the highest score in the resources and outcomes pillars of the rankings. Meanwhile, Akita International University tops the environment pillar and also comes first for engagement, which measures the quality of university teaching through a survey of student career advisers.

ellie.bothwell@timeshighereducation.com

Top 10 institutions in the THE Japan University Rankings

| Rank | Institution | Prefecture |

| =1 | Kyoto University | Kyoto |

| =1 | The University of Tokyo | Tokyo |

| 3 | Tohoku University | Miyagi |

| 4 | Tokyo Institute of Technology | Tokyo |

| 5 | Kyushu University | Fukuoka |

| 6 | Hokkaido University | Hokkaido |

| 7 | Nagoya University | Aichi |

| 8 | Osaka University | Osaka |

| 9 | University of Tsukuba | Ibaraki |

| 10 | Keio University | Tokyo |

View the full results of the Times Higher Education Japan University Rankings 2018

Trading on reputations

Is the quality of teaching in Japan’s top universities on a par with that of their research?

Do “top” universities provide the best teaching? That question has long been moot, given the extent to which institutional reputation is formed by research performance. The sometimes surprising results of the UK’s teaching excellence framework last year suggest that the connection between a high-ranking university and a good student experience is certainly not guaranteed.

In Japan, the question is particularly subject to debate given the country’s unfortunate international reputation for discouraging critical thinking and creativity in its education system. Few data exist on teaching quality in Japanese universities, but the Times Higher Education Japan University Rankings, launched last year and repeated this year, provide some insights.

Search for university jobs in Japan and throughout Asia

The ranking is modelled on the Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education US College Rankings, which were first published in 2016. Overall scores are constructed on the basis of the same four “pillars” – resources, engagement, outcomes and environment; see our methodology – all of which focus primarily on what institutions offer students. In that respect, the rankings differ considerably from THE’s World University Rankings, which are primarily informed by research data.

Top 20 institutions for environment

Top 20 institutions for outcomes

| Rank on outcomes pillar | Rank in overall Japan University Rankings 2018 | Institution | Score on outcomes pillar |

| 1 | =1 | The University of Tokyo | 98.9 |

| 2 | =1 | Kyoto University | 98.6 |

| 3 | 5 | Kyushu University | 97.7 |

| 4 | 10 | Keio University | 97.2 |

| =5 | 7 | Nagoya University | 95.6 |

| =5 | 3 | Tohoku University | 95.6 |

| 7 | 8 | Osaka University | 95.4 |

| 8 | 6 | Hokkaido University | 94.8 |

| 9 | 4 | Tokyo Institute of Technology | 94.7 |

| 10 | 11 | Waseda University | 93.8 |

| 11 | 14 | Hitotsubashi University | 89.1 |

| 12 | 9 | University of Tsukuba | 88.1 |

| 13 | 13 | Hiroshima University | 76.6 |

| 14 | 30 | Tokyo University of Science | 73.2 |

| 15 | =25 | Yokohama National University | 72.9 |

| 16 | 19 | Chiba University | 72 |

| 17 | 12 | Akita International University | 70.6 |

| 18 | 29 | Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology | 69.6 |

| 19 | 15 | Sophia University | 69.4 |

| 20 | 18 | Kobe University | 69.3 |

At first glance, comparing the two rankings suggests that Japan’s performance in teaching is not vastly different from its performance in research. The Japan rankings are headed by The University of Tokyo and Kyoto University, which are also Japan’s highest-ranked representatives in the THE World University Rankings, at numbers 46 and joint 74th, respectively. Third is Tohoku University, which is Japan’s joint-third highest representative in the world rankings. And the country’s fifth in the world rankings, the Tokyo Institute of Technology, is fourth in the Japan rankings, produced in partnership with Japanese education company Benesse.

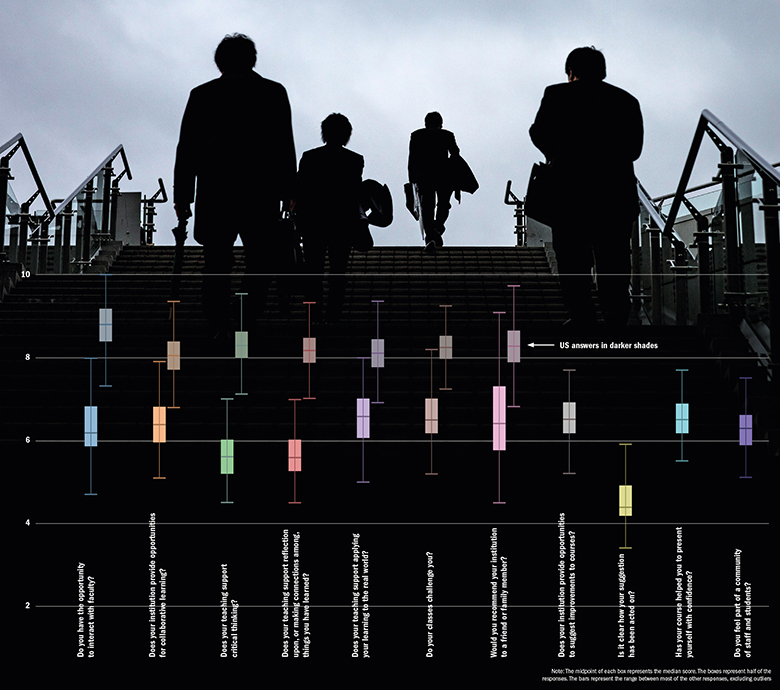

However, in preparing this year’s rankings, THE also directly surveyed undergraduates at Japanese institutions about teaching at their universities. The survey – which was carried out on a trial basis and does not feed into the main rankings this year – assesses opportunities for interacting with faculty, as well as the extent to which teaching challenges students, enhances their critical thinking and helps them see connections between different aspects of their courses and apply their learning to the real world. It also examines whether universities seek suggestions for improvements from students and act on them, and whether students would recommend their institutions to family and friends.

The results of the survey will be published later this year, but an early look at the data suggests that Japanese students are critical of the quality of their teaching. It also reveals that some of Japan’s top institutions fall down when it comes to many aspects of teaching. Tokyo and Kyoto, for example, are the worst institutions out of the 87 surveyed at supporting students to apply their knowledge to the real world.

See our methodology for the THE Japan University Rankings 2018

In fact, all of Japan’s top 10 universities overall perform particularly badly on this aspect of teaching. The institutions highly ranked in the main rankings also score poorly on the extent to which they challenge students, foster a sense of community and provide students with opportunities to interact with faculty.

Among the country’s elite, the University of Tsukuba stands out as offering the best-quality teaching across all the metrics in the student experience survey. It is the only institution highly ranked in the main survey to break into the top 25, when the results of the survey are amalgamated into a ranking. And it scores particularly well compared with its top 10 peers for student interaction with faculty, the challenging nature of its teaching and the support that it gives students to reflect on or make connections between educational content.

Tokyo and Hokkaido University are the only other institutions highly placed in the Japan rankings to come anywhere near the top on specific aspects of the student experience, with both scoring above average on developing critical thinking.

By contrast, Japan’s international universities, which teach many of their courses in English, perform strongly in the survey. Akita International University (12th in the main Japan rankings), the International Christian University (16th) and Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University (joint 21st) do particularly well in areas such as communication between staff and students. This may partly be explained by the nature of such institutions, which work to prepare students for a global marketplace that is competitive, and value skills such as critical thinking.

By contrast, the local job market in Japan is more focused on the reputation of the universities that graduates attended than on the skills or knowledge that they gained there. This may explain why, for all their apparent failings in teaching quality, students at the highest-ranked universities still typically say that they would recommend them to others. Tokyo, Kyoto and Tohoku have some of the biggest disparities between the perceived quality of their teaching and their students’ likelihood to recommend them.

Simon Marginson, professor of international higher education at the UCL Institute of Education, says that such a phenomenon is not uncommon in countries with competitive and hierarchical higher education systems. “Student choice has never been primarily driven by actual or perceived teaching quality, learning achievement or satisfaction with services or facilities,” he says. Instead, the status of the university and degree course and the sense of how the programme leads to a career are more important.

Marginson is “wary of playing into” the narrative that Japanese universities are poor at teaching critical thinking, noting that the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Pisa ranking of school-level education shows that East Asian countries do “relatively well on critical thinking and problem-solving”. Recent educational reforms in Japan, South Korea and China have also pushed important themes around “fostering individuality, criticality and students who speak up in class”, he adds – although he admits that this has been less of a focus in higher education.

But Devin Stewart, senior programme director and senior fellow at the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs in New York City, says that while there is some degree of “lip service” paid to critical thinking in Japan, “it is not being taught as much as it should be”. His own research suggests that the emphasis in Japanese education remains on memorisation and obedience. “In the US, the received wisdom is to question everything. In Japan, it is the opposite,” he says. “They therefore risk falling behind in the 21st-century economy.”

Japan has the highest level of debt of all countries in the OECD and its universities have been battling chronic underfunding since the early 1990s, Stewart says. They are struggling to internationalise, and their research standing, in terms of the number of academic papers and highly cited journal articles produced, is in decline.

Top 20 institutions for engagement

| Rank on engagement pillar | Rank in overall Japan University Rankings 2018 | Institution | Score on engagement pillar |

| 1 | 12 | Akita International University | 100 |

| 2 | =1 | The University of Tokyo | 100 |

| =3 | =1 | Kyoto University | 100 |

| =3 | 3 | Tohoku University | 100 |

| 5 | 11 | Waseda University | 99 |

| 6 | 10 | Keio University | 99 |

| 7 | 9 | University of Tsukuba | 99 |

| 8 | 8 | Osaka University | 99 |

| 9 | 5 | Kyushu University | 98 |

| =10 | 16 | International Christian University | 98.1 |

| =10 | 4 | Tokyo Institute of Technology | 98.1 |

| =12 | 35 | Meiji University | 97.7 |

| =12 | 7 | Nagoya University | 97.7 |

| =12 | 15 | Sophia University | 97.7 |

| 15 | 6 | Hokkaido University | 97.4 |

| 16 | 13 | Hiroshima University | 97.1 |

| 17 | 14 | Hitotsubashi University | 96.6 |

| 18 | 28 | Doshisha University | 96.3 |

| 19 | 27 | Rikkyo University | 96.2 |

| 20 | 23 | Ritsumeikan University | 96 |

Top 20 institutions for resources

| Rank on resources pillar | Rank in overall Japan University Rankings 2018 | Institution | Score on resources pillar |

| 1 | =1 | The University of Tokyo | 85.4 |

| 2 | =1 | Kyoto University | 84.7 |

| 3 | 3 | Tohoku University | 83.4 |

| 4 | =39 | Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) | 82.5 |

| 5 | 141-150 | Hamamatsu University School of Medicine | 81.2 |

| 6 | 141-150 | Shiga University of Medical Science | 79.7 |

| 7 | 151+ | Hyogo College of Medicine | 79.6 |

| 8 | 151+ | Tokyo Medical University | 79.5 |

| 9 | 141-150 | Sapporo Medical University | 78.6 |

| 10 | 8 | Osaka University | 77.9 |

| 11 | 4 | Tokyo Institute of Technology | 77.6 |

| 12 | =68 | Toyota Technological Institute | 76.7 |

| 13 | 151+ | Asahikawa Medical University | 76.4 |

| 14 | 151+ | Nippon Medical School | 76.3 |

| 15 | 151+ | Nara Medical University | 76.1 |

| 16 | 141-150 | Fukushima Medical University | 75.8 |

| 17 | 6 | Hokkaido University | 75.3 |

| 18 | 9 | University of Tsukuba | 75 |

| 19 | 5 | Kyushu University | 74.8 |

| 20 | 151+ | Osaka Medical College | 74.3 |

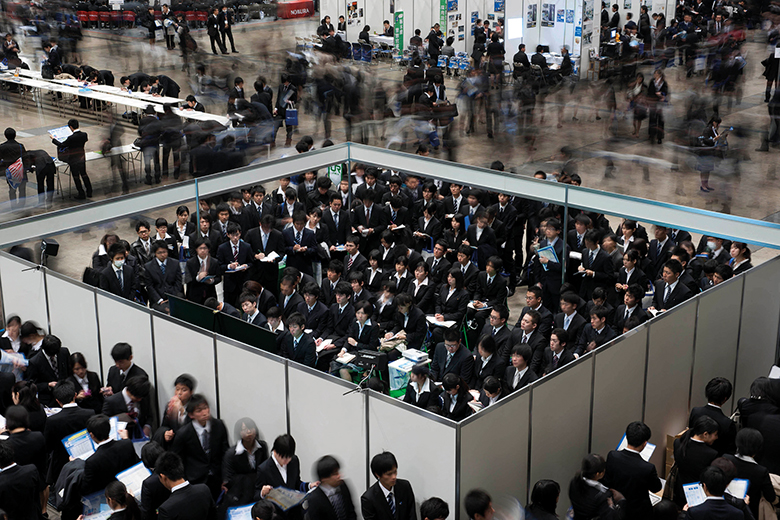

Takehido Kariya, professor in the sociology of Japanese society at the University of Oxford, says that the curricular structure in Japanese universities is very different from that of countries where critical thinking is a key tenet of higher education. Students usually register for 12 to 15 different subjects per term but do not necessarily attend all classes. “Most of those classes are lectures, with a few reading assignments and writing essays, meaning students just sit in a large lecture room to listen to lectures and to take notes, without any preparations or any assigned works afterwards,” he says.

“This kind of lecture-centred teaching style has developed under the financially restricted conditions of higher education institutions in Japan, most of which are poorly funded private institutions,” Kariya adds.

Comparison of US and Japanese universities’ scores in the student survey

If you take Japanese universities as a whole, the scores that they receive for teaching in the student survey are strikingly lower than the scores that US universities receive in the student experience survey that feeds into the THE/Wall Street Journal US College Rankings, which features many of the same questions. The disparities are particularly striking when it comes to universities’ willingness to seek and act on student suggestions.

Moreover, the greater spread of scores in Japan suggests that teaching quality is less consistent – or, alternatively, that there is less consensus among students as to what good teaching looks like.

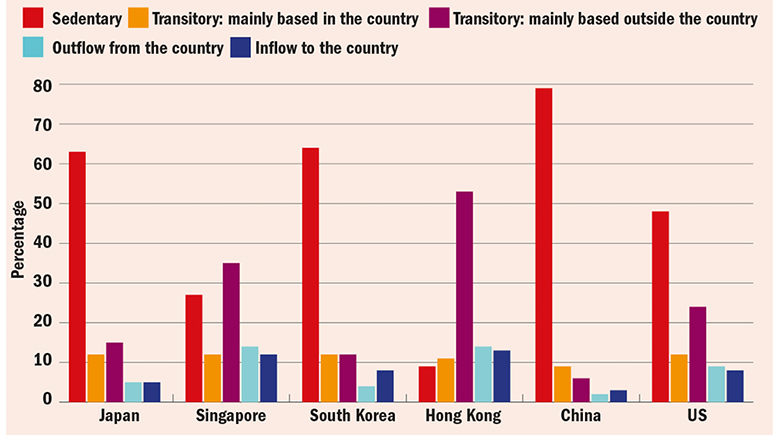

International researcher mobility

Source: SciVal/Elsevier, drawing on data from 1996 onwards. Note: Sedentary = researchers have not published with affiliations outside of Country X. Outflow = researcher first published in Country X and subsequently migrated for at least two years without returning OR researchers migrated to Country X, stayed for at least two years, and then migrated to another country for at least two years without returning. Inflow = researchers first published in a different country before staying in Country X for at least two years OR researchers first published in Country X, migrated to another country for at least two years, then returned to Country X for at least two years. Mainly based in the country = researchers mainly published with affiliations in Country X and spent less than two years abroad before returning. Mainly based outside the country = researchers published mainly from abroad and spent less than two years in Country X before migrating to another country

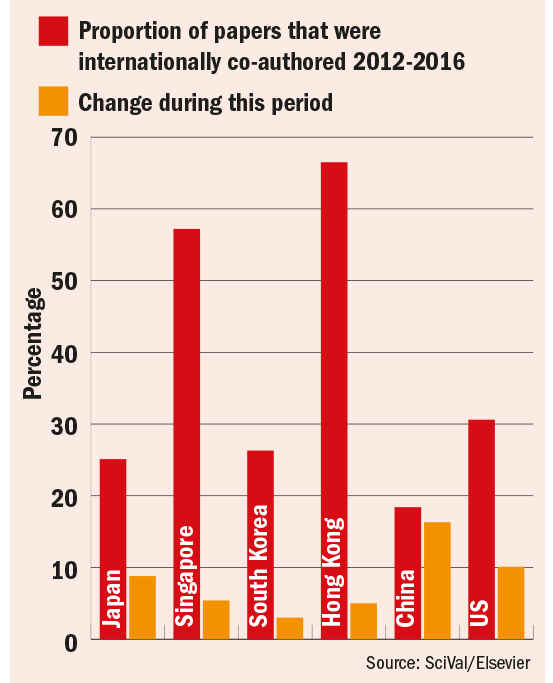

Internationalisation

This year’s main Japan rankings introduces additional metrics on the extent of internationalisation in universities, based on how many classes are taught in a foreign language and the extent of international exchange programmes. Next year, THE will also integrate the results of the student survey into the main rankings – a move that could shake up the existing hierarchies in Japanese higher education and stimulate some hard thinking among university leaders and policymakers.

But, however much Japan may currently be languishing, Marginson is convinced that all is not lost. He insists that it is well within the nation’s capacity to emulate “previous periods of great nation-building in higher education”, between 1870 and 1910, and between 1960 and 1990.

“Japan is an immensely capable country in terms of public and private intelligence,” he notes. “If it decides to renew the higher education sector, it will do so very quickly…History never stands still.”

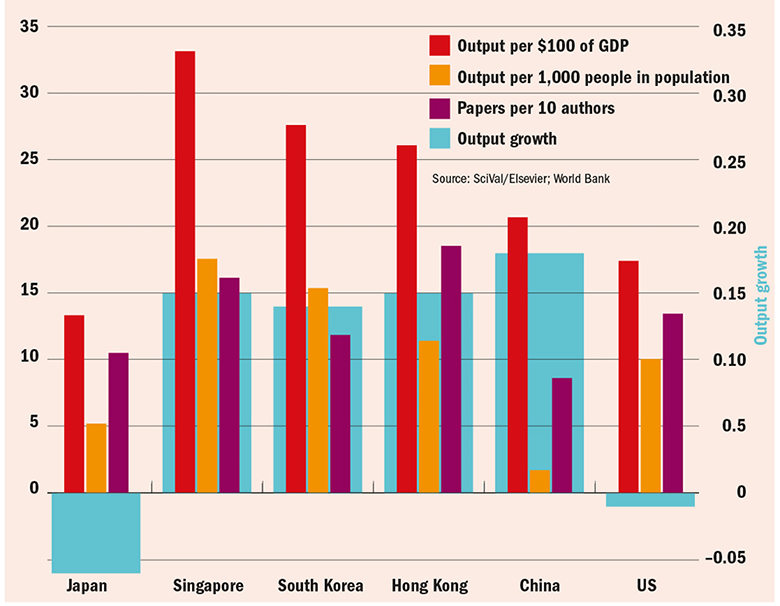

Measures of productivity, 2012-2016

holly.else@timeshighereducation.com

Japan’s super-global ambitions

Enter the name of Japan’s foreign minister, Tarō Kōno, into the country’s version of Google and you will find that the top-ranked results are not about his stance on North Korea but his English ability. Widely read blogposts wonder aloud: “His English is too good; is he really a native?”

Tales of shy Japanese students unable to utter foreign words are a staple of the country’s cultural landscape. They drove – at the behest of then prime minister Yasuhiro Nakasone’s “internationalisation” campaign – the establishment of the aggressive, informal English conversation industry, known as eikaiwa, during the boom years of the 1980s. The prize commodity of these institutions was the “native kyōin ” (teacher): young students or recent graduates hired on six- or 12-month visas, and always photographed with big smiles in the schools’ publicity materials.

Some eikaiwa have been effective. Others squandered their potential, treating their minimally trained teachers as cheap, disposable dolls, whose mere appearance and accent was assumed to generate cosmopolitanism by osmosis. Eikaiwa’s tawdry reputation hit the international headlines in the mid-noughties, when the giant Nova Corporation ran into financial trouble, leaving students without teachers and 4,000 teachers unpaid.

But the internet created new opportunities, with lessons from “natives” charged at a premium rate. Meanwhile, schools hired more foreign assistant language teachers and the Ministry of Education began to require conversational English from grade five; soon fifth graders will have regular English, with conversation from grade three.

In addition, in 2002, the opportunity to learn other subjects in English was introduced at school level by the Super English Language High Schools initiative. The idea migrated to higher education with the Global 30 plan from 2009-13 and the Super Global initiative in 2014. These programmes mandate degrees exclusively taught in English, increased numbers of international students, more opportunities for instruction in other languages and increased study abroad opportunities for Japanese students.

In the days when families had too many children and not enough money, parents often concentrated resources on their favourite child. A similar pattern can be observed in higher education, wrote education scholar Kazuyuki Kitamura in 1986. In the post-war growth period, Japan planned “to concentrate educational resources in the public sector in order to preserve academic quality, while leaving quantitative expansion to the initiative of private institutions, which grow more flexibly according to changing popular needs”.

A similar pattern persists in today’s Super Global initiative, which encompasses 37 “top universities”. These institutions have restructured some courses using English as a medium of instruction, aiming for compatibility with programmes abroad or those taught in Japanese, and each university allocates considerable resources to recruit students from throughout the world. Indeed, the government has set targets to raise Japan’s profile in international education through its 300,000 Foreign Students Plan, which aims to have 10 per cent of the country’s student population made up of overseas students by 2020: on a par with Germany.

Not to be left out, the rest of Japan’s 800 universities – alongside the Super Global universities themselves, which groom some of their departments more than others to carry their reputations in global assessments – have been launching English-speaking “spin-off” departments since 2010. Like eikaiwa, their quality varies widely. The top tier outside the Super Global initiative aim at the same standards as those of the designated Super Global departments. But others might be just former language schools given a cosmetic makeover. Creative course titling has seen upper-level coursework refashioned as sociology, economics, international relations or other “subjects”, even when the instructors have no degrees or publications in those fields. Such “ESL content” classes are common in the early stages of language learning, but in spin-off departments they appear as regular classes to students who have already moved beyond ESL.

In this way, universities inflate their “global” curriculum while making their spin-off departments attractive to younger, inexperienced teachers on short-term contracts. These teachers are given high status but are burdened with significantly more classes than colleagues in other departments.

At the same time, senior international and Japanese staff in spin-off departments, hired with masters and doctorates in specialised subjects, have found themselves teaching classes that formerly had open curricula but have been officially redesignated as ESL (English as a second language) – requiring managed oversight and standard, commercial texts. And because not all students across the university achieve high English scores, universities force even senior faculty in second-tier spin-offs into other departments to teach low-level English. It has long been a contentious point whether literature faculty should be forced to teach language, but now professors in other fields are caught in the trap.

In some cases, Japanese students study credit-bearing subjects in English at foreign universities, only to return to Japan to take the same subjects with language teachers. Students in spin-off departments can get stuck in perpetual ESL, which contradicts the original goals of the Super Global initiative to move beyond ESL. This is a cash cow for the language services industry, whose sales representatives stalk the corridors of the new university departments, trying to convince their heads that they need to purchase standard ESL textbooks, prefabricated final exams, and mock and real materials to administer the most common official language exams. Departmental websites boast of rising test scores, while educational businesses raise their profiles with data and blandishments for big-name universities.

Like the eikaiwa, spin-off global departments show off their native speakers. Full-time international teaching faculty, whether ESL specialists or not, are hired with titles corresponding to the American system of assistant, associate or full professor. Once hired, they are depicted on web pages in nurturing poses, with students commenting on how fun their lessons are and what a positive impact they have had on their Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) scores.

Foreign teachers, especially women, might be greeted by their first names (in Japanese society, adults and professionals routinely use family names; first names may be deployed to insult or cutify someone). Eikaiwa lessons explain that all foreigners use first names, so asking people to do otherwise creates irritation and boundary confusion. Segregation of teaching staff also carries over into departmental emails and administrative work, as when Japanese staff create departmental discourse and foreign faculty are asked merely to do a “native check” on it.

If Japanese universities no longer want language departments, what about attached vocational schools, similar to the extension programmes in overseas universities, staffed with outsourced teachers doing remedial ESL – possibly with transferable credit? A few universities have tried this, but the answer that I typically get when I suggest it is a resounding “no” – with an excuse that administrators see outsourcing as somehow untrustworthy and contrary to Japanese culture.

Perhaps the reluctance to go down this outsourcing path has to do with reversing the slide of Japanese universities in global rankings. Over the past few decades, professionally minded ESL teachers have shied away from eikaiwa in favour of the three- to five-year contracts offered by universities, helping to raise the number of international faculty countable in rankings. Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings, for instance, counts those who are full-time employees of the university, either tenured or with long-term contracts. However, universities’ proportion of international faculty accounts for only 2.5 per cent of overall scores in the THE ranking, so increasing it does not actually do much to raise overall scores.

In the 19th century, foreign teachers, known as gaikokujin kyōshi, joined a wave of foreign advisers invited to Japan to assist with its modernisation programme, but only a few were allowed to stay. And as recently as 1992, the Ministry of Education warned all national universities not to allow foreign teachers to stay long enough to become eligible for a pension. Many American, British and other foreigners who had lived in Japan for many years – an estimated 70 per cent of whom were over 45 years old – were suddenly fired and replaced by much younger teachers on short-term contracts. Negative international publicity and high-level intervention prompted a new wave of reform in Japanese universities. But while some institutions had already given up the non-status for foreigners, the more stubborn retained the title of gaikokujin kyōshi for all foreigners, regardless of specialisation, until 2004.

Even today, the “native kyōin” who comes to Japan intending to teach, typically ends up as an object to be studied. The discrimination is subtle compared with other examples of prejudice in the world, but it is pernicious in its normalisation. One department, for instance, writes in its policy statement that its Japanese faculty have degrees in various subjects such as sociology, politics and literature, whereas “the five English native teachers each have master’s degrees in English education, applied linguistics, TESOL [Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages] or TEFL [Teaching English as a Foreign Language]”.

True, language learners benefit from listening to and modelling native speech. Beyond a certain point, however, “native” obsession diverts Japan-based global programmes from what they are supposed to emulate: the actual experience of studying abroad. Japanese students overseas are initially surprised when their teachers have a variety of ethnic, national and professional backgrounds – they are not all “native” and not all are English teachers.

I once had to ask a Japanese student in California why he had been skipping class.

“I thought that it would be better for my English to go off-campus and just meet native [speaker] Americans,” he answered.

Marie Thorsten is a research fellow in the Social Science Research Institute at the International Christian University, Tokyo.

Browse the full list of institutions in this year’s rankings

后记

Print headline: Trading on reputations