The make-up of the next Italian government is still unclear after March’s general election led to a hung parliament. However, regardless of which parties eventually succeed in forming a viable coalition, it appears unlikely that the new government will do much to arrest the long decline of Italian academia.

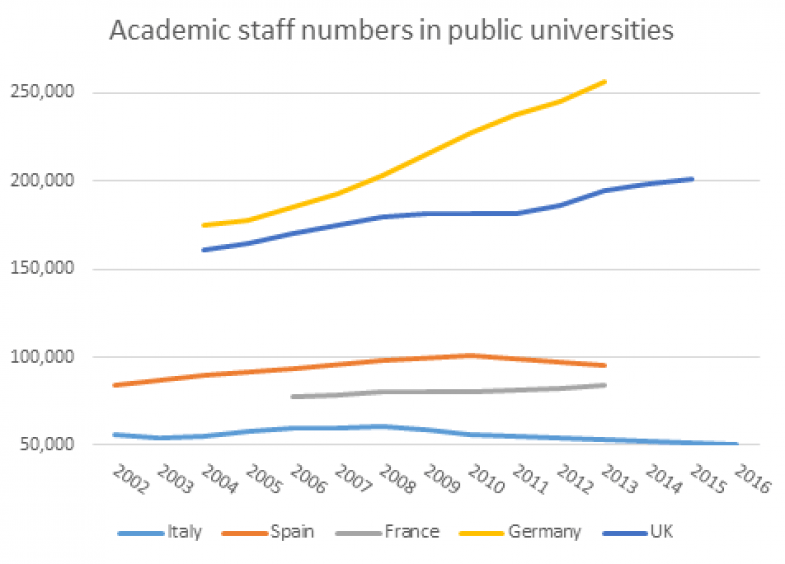

The figures are startling. A recent study by HERe, a research centre run by the Conference of Italian University Rectors Foundation and the University of Bergamo, compared the total number of academic staff employed in the public university systems of the largest western European countries. It found that the Italian system employs about 50,000 academics, compared with 80,000 in France, 95,000 in Spain, 200,000 in the UK and more than 250,000 in Germany.

The Italian count would grow by 13,000 if research fellows (assegnisti di ricerca: usually non-tenured postdoctoral researchers) were included, but that would still leave Italy far behind the other countries.

It is also worth bearing in mind that Germany, France and Spain also have many academics employed in research institutes, who are not included in the above figures.

Moreover, since the beginning of the new millennium, Italy is the only large western European country to have decreased its overall endowment of academic staff. The comparison with Germany is particularly mind-boggling. The German system has increased its academic staff count by 75,000 in a decade: more than the entire current academic headcount in Italy.

Clearly, this situation needs to be addressed, but doing so would not be financially straightforward for a country with one of the largest public debts in the eurozone because personnel is the main cost item on the balance sheets of universities. The total costs of Italian university salaries, which includes both academics and professional and support staff, was €7.4 billion (£6.5 billion) in 2014. This is mostly covered by the government’s “Ordinary Financing Fund” (FFO), which amounts to about €6.9 billion per year. The rest is met from tuition fees, which generated about €1.8 billion in 2016.

The Democratic Party of former prime minister Matteo Renzi started to reinvest in the university system when it was in power, increasing the FFO in 2017. Moreover, the party’s election manifesto promised to fund the hiring of 10,000 tenure-track assistant professors over the next five years. However, its coalition won only 23 per cent of the vote, so it would not be the major partner in the new government.

In general, university financing was only a marginal issue in the election campaign. There was interest from the public in a proposal from the small left-wing party Free and Equal (Liberi e Uguali) to abolish tuition fees and to increase grants for students. The same party also proposed to negotiate with the European Union the funding of 20,000 additional academic staff positions out of the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact over the next five years. But the party won only about 3.5 per cent of the vote.

Of the parties and coalitions likely to lead the next government, the Five Star Movement, which won 32.5 per cent of votes, declares an intention to increase the FFO – although it does not specify by how much. It also pledges to link the fund's allocation to, among other factors, the recruitment of young researchers.

The centre-right coalition, which contains both the League and Forza Italia parties and won about 37 per cent of the vote, decreased the FFO by €1.4 billion when it was in government between 2009 and 2013. It also introduced temporary employment in the higher education sector, replacing tenured assistant professorships with non-tenured ones. It has now pledged to progressively eliminate temporary employment and to “relaunch” the education and research sector, but it has also failed to give any figures for investment and hiring.

Such vague rhetoric does not inspire confidence that the next Italian government will be in any hurry to follow through with hard cash to grow Italian higher education to a more internationally competitive size.

Davide Donina is a postdoctoral research fellow in the department of management, information and production engineering at the University of Bergamo, where he undertakes research on higher education policy and governance, particularly on the Italian sector.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: A lean and hungry look

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?