A few years ago internationalisation was all the rage in higher education. If you wanted your university to be noticed on the world stage then you needed a global strategy.

This was true even for institutions that were not necessarily part of the increasingly cross-border nature of research. In the UK and elsewhere, international student recruitment is now vital to keeping a healthy balance sheet in most universities, so a global outlook is a given.

The general public was, at worst, agnostic to this strategy and at best supportive. But there has been a sea change in the attitude towards universities in past few years, especially in Europe and North America, as the rise in popularism fuels increasing scepticism about higher education. As a result, many people – and therefore governments – are asking more and more about the impact universities make closer to home.

For those working in higher education, the answers are obvious: a better educated, more highly skilled population; a huge economic impact; the list goes on. But central to universities trying to stay onside with the public in this age of scepticism is finding ways to demonstrate this.

The problem is that many of the metrics and data that universities – and others – use to measure performance are by their very nature global. A common way of assessing the impact of research, for instance, involves looking at worldwide citations.

Finding data that can better measure local impact across national boundaries would be a boon for higher education.

This is a challenge that is the main topic of discussion for a session being led by Times Higher Education at the Going Global education conference, in Malaysia this week, 2-4 May.

Some of the key questions that will be discussed include pinpointing the kind of aspects of local impact that would be useful, what metrics would be needed to measure them and whether it would ever be possible to compare them between countries.

In an attempt to frame this debate, THE will present a new analysis of data from the 2018 World University Rankings to show that although the ranking is designed to compare research-focussed universities across the globe, there are still local and regional insights we can draw from them.

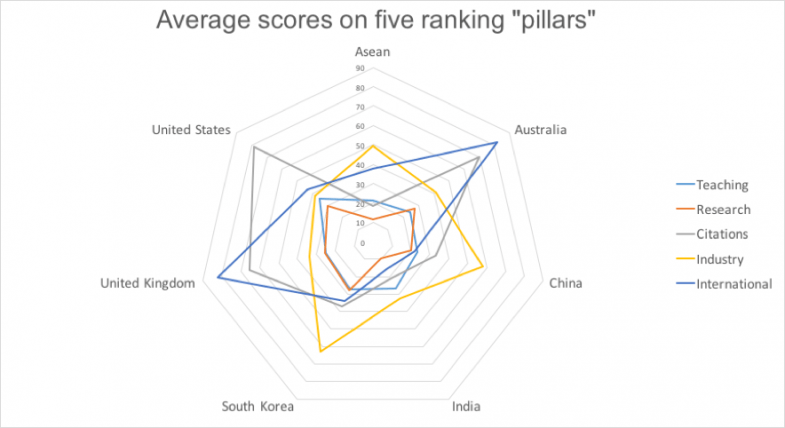

For instance, the new analysis shows how the nations of South East Asia are building a successful regional higher education network centred around the cross-pollination of research and student movement. This graph, which shows how members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) compare on average “pillar” scores in the ranking with major countries, provides a taste of this data.

At the same time, it is also clear from the data that there are still severe limitations and challenges to using international rankings to show local impacts. But the development of country and regional THE rankings for the US, Japan and, soon, Europe hints at the possible way forward.

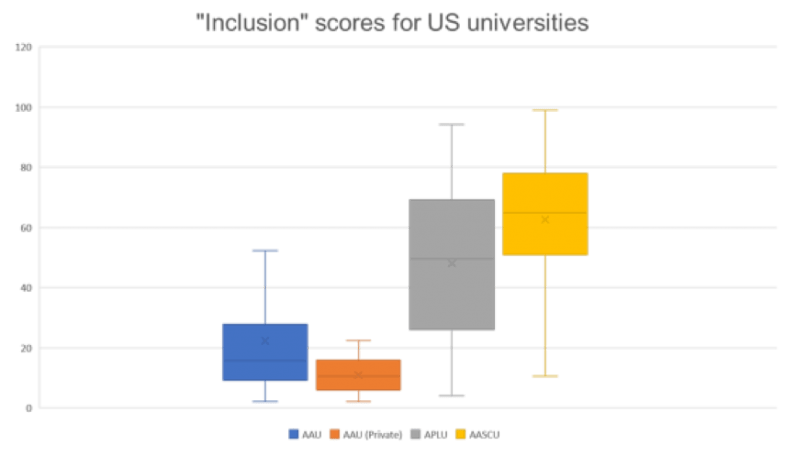

For example, the Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education US College Rankings have used sophisticated measures of student diversity in an attempt to measure how much universities in the country are widening participation, a key “local” concern for many governments.

Some of the potentially interesting results of this are shown by the below graph from the Going Global presentation. It shows the distribution of scores (the boxes show where the middle half of institutions sit, with the line being the median) for different groups of US institutions on “inclusion” the metric which measures how many students they admit from low-income backgrounds.

.

The major challenge is taking these kinds of insights and findings to the next level by comparing universities in completely different parts of the world on the same sort of metrics. It is not going to be easy: if we measure inclusion in the US by looking at data on students claiming government grants for instance, how do we compare that with data on students from low-participation neighbourhoods in the UK?

However, if this kind of dilemma can be cracked, a new window will open on the performance of universities, one that can potentially unlock the door to showing the value of higher education to local populations the world over.

Simon Baker is data editor at Times Higher Education. He will be facilitating the session Global Rankings: measuring local impact on Wednesday 4 May at 16:45 at the Going Global conference in Kuala Lumper.