Since the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke last October, launching the #MeToo movement, there has been a great deal of talk about sexual harassment in academia.

One recent example is a report by the Australian Women’s History Network (AWHN), which exposes a disturbing collection of inappropriate and widely underreported behaviours, from gendered bullying to sexual coercion, predation and even assault.

One recurring scenario that was reported by survey respondents involved female PhD students being pressured into sex by their male supervisors. According to the authors, “Respondents wrote about being lured into men’s offices, hotel rooms or homes on a professional pretext, and then having to fend off unwanted sexual advances. In many cases, coercion and intimidation were involved.”

These reports draw attention to the complex interplay of gender and power in academia, while pointing to the need for structural change, including both the decentralisation and diversification of institutional authority. However, the report’s focus on “top‑down” discrimination overlooks another important aspect of this multifaceted problem, which is the fact that many female academics are sexually harassed by students, too.

This is known as contrapower harassment and it occurs when someone with seemingly less formal power in an institution harasses someone with more formal power.

Nearly 35 years ago, psychology academic Katherine Benson called for research on sexual harassment in academia to investigate the problem of contrapower harassment, so that systematic data on the issue would become available. The phenomenon has since been well documented in American institutions, with several studies finding that academic contrapower harassment is now a routine part of being a university educator in the 21st century.

In the Australian context, however, there is a lack of formal research surrounding academics’ experiences of this type of harassment, including its statistical occurrence and the effectiveness of institutional policies and processes put in place to deal with such reports. This is why preliminary research, such as that conducted by the AWHN, is important.

In the absence of hard data, let me tell you my own story.

I’m 31. I completed my undergraduate degree 10 years ago, after which I started working as a tutor in creative writing and literary studies while I earned my PhD. Since then, I have worked mostly as a lecturer, teaching and conducting research at a handful of respected universities, both in Australia and abroad.

During this time, I, like many of my colleagues, have been frequently harassed – mostly by male students – both in and out of the classroom.

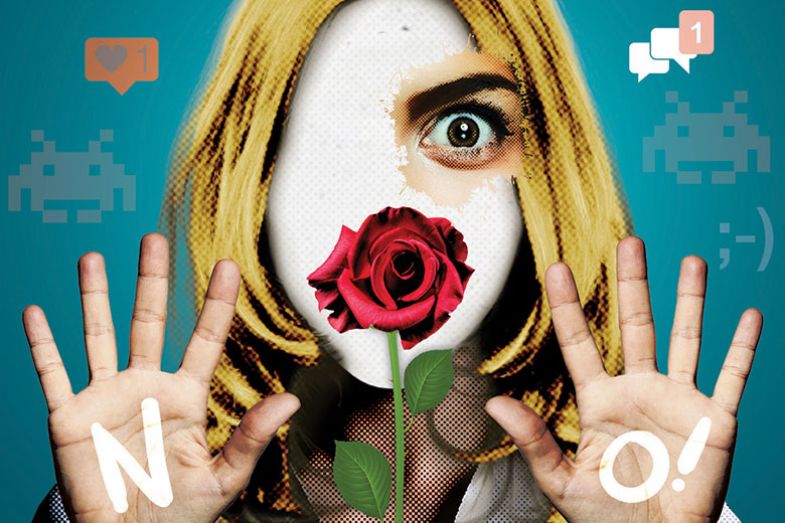

I have been propositioned for sex and bombarded with unwelcome advances and unwanted gifts, such as roses, chocolates and, on a few occasions, bad poetry. One poem, submitted to me for assessment in a creative writing class, was titled Back Door Entry. The poem was about a female teacher who gets gang-raped. Coincidentally, she also had the same name as me. I flagged the poem with a senior colleague who agreed that it was offensive but discouraged me from pursuing the matter further for two reasons: first, students have a right to express themselves creatively, even if their work is offensive, and, second, I had no proof that the subject of the poem was me.

I have also been stalked, both online and on-campus, and forced, more than once, to change my phone number. In London, I contemplated moving house when a student found out where I lived and turned up at my apartment with a black bag, pretending to be an Uber Eats delivery guy. The next day, the same student came to class as if nothing had happened. A few weeks later, he sent me a link to his blog: a strange collection of mostly nonsensical meanderings, in which he confessed to having sexual fantasies about me.

At the time, I didn’t report the student to my supervisor because I was in a new, non-tenured position, and I was worried that the situation would be perceived as a failure on my part to garner respect or to cope with the demands of the job. I also felt misplaced empathy. The student had also confided to me that he was staying in England illegally, and I was concerned that if I said something, he would be deported.

The AWHN, in its recent survey, found that many academics who experience sexual harassment do not formally report their experiences for a variety of reasons, including their employment status if they’re untenured, a fear of being labelled a “troublemaker”, and the belief that formal processes are ineffective or unsupportive.

In any workplace, contrapower harassment can be covert or overt. Recently, Jan Wynen, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Antwerp, used data from a large-scale survey of the Australian public service to show that age is a significant factor when it comes to the relationship between gender, workplace authority and sexual harassment. The study found that women younger than 30 are far more likely to be sexually harassed than women over 30. In addition, women with supervisory authority aged between 30 and 44 are more likely to be sexually harassed than colleagues without the same authority. The study concluded that since the Australian government is expected to be more sensitive to issues of gender and equity, the existence of contrapower sexual harassment may be even more pronounced in the private sector.

I want to be clear about my students. Most of them are brilliant, intelligent, sensitive people. Usually, they respect themselves and each other, and, nine times out of 10, our interactions are enjoyable and productive. Most of my students are goodhearted. Most of them are genuinely appalled when they ask me what it’s like to be a young female academic and I tell them honestly: it’s great, and it’s also not so great.

But at other times, my personal space has been violated by students. I think of them as “space invaders”, but that is really quite a benign label for their behaviour. A few years ago, for instance, I had a male student, no older than 20, who frequently took photos of me on his iPad while I was lecturing. I found out because he showed the photos to me. I reported him to my head of school, and she immediately called him into her office for an informal meeting. However, when she reprimanded him, he didn’t understand what the problem was. He told her we were in love.

He was issued with a verbal warning and continued to attend my class. To my knowledge, the photography stopped, but my discomfort remained.

Sometimes, I have felt targeted simply because I am a woman – and, perhaps more specifically, because I’m a young woman in a position of authority. The power-threat model of sexual harassment suggests that women with formal power, who hold authority over men, challenge cultural expectations of male dominance, which makes them more likely to face harassment. In official evaluations of my teaching, students have made inappropriate comments about my clothes, my make-up and my body. These comments focus on the way I look, or how I dress, rather than the quality of my teaching. Examples of these comments include “great hair and smile”, “more out-of-class help (winky face emoji)”, and “class would be better if we went on a date”.

There’s mounting evidence to suggest that student evaluations of teaching are not only biased against female instructors, but that these evaluations are more effective at identifying students’ gender (and racial) bias than measuring teaching success.

It’s also important to remember that academic contrapower harassment, like other forms of sexual harassment, is a complex socio-cultural problem that cannot be understood in simple binary terms, such as “young” and “old”, or “male” and “female”. In fact, I have been harassed by female students, too. At a Queensland University, while on lunch in the quad one day, a third-year approached me somewhat brazenly and warned me to stay away from her girlfriend (another student of mine) because her girlfriend wanted to bash me. When I enquired as to why, she laughed: “We were having sex last night and I accidentally said your name.” The same student regularly wrote about me on a blog about “professional lust”, and sent me a link to her website so that I could read her weekly posts. A few years later, she apologised.

Countless times – more times than I can remember – I have been made to feel powerless in my own classroom. At one point or another, during a class discussion, students have made sexual jokes or sexist remarks. Usually they haven’t meant harm, but their comments are still offensive.

Sometimes, when finishing late, I have had to call security to accompany me to my car because I have found an idle student waiting for me outside my office or in the car park. Usually, these students just want to have a chat or ask a follow-up question, but as a woman, alone, on a campus where young women have been sexually assaulted, I’m afraid.

At times, I have regretted outfit choices and wished that I’d worn jeans or trousers instead of a skirt. I have actually thought to myself: “I should wear bright clothes next week, so that my body is easy to find.” I have joked with colleagues that our classrooms need panic buttons – some kind of direct line to security, faster and more subtle than a phone call. We’ve joked about it, but it isn’t funny.

And still, I worry about my students. I worry about the young woman with high distinctions who, in week five, stops coming to class because she feels threatened by the student who found out where she lives and turned up to her dorm on Friday night with a bouquet of roses, dressed for an obviously unplanned and non-consensual date. I worry about her well-being and I worry about the offender himself. I worry because he’s a future teacher, editor, politician, lawyer or journalist. When he graduates, he’ll enter the workforce. He’ll earn a good salary. Maybe he will get promoted. Maybe he will assault someone. Maybe, if he gets away with it, he’ll think how easy it was. He’ll feel confident. Strong. Entitled. He will do it again.

I worry that if we don’t expect more of our students, if we don’t hold them accountable for their words and actions, we will never end systematic discrimination, not only in our universities but also in the various workplaces they will eventually lead.

Most universities have a student code of conduct that provides a general framework for acceptable standards of behaviour; however, these codes, while clearly articulated, are often unable to account for the varied and complex situations that arise in practice. What’s more, most students only find out about their university’s code once they’ve breached it. We can’t expect students to abide by a code they don’t know exists; all students should be required to read and agree to it as part of their enrolment.

I also worry that if we can’t access clear and supportive reporting mechanisms, without fear of retaliation or reprisal, then more cases of assault will go unreported.

At the moment, there are about four times as many casuals as permanent full-time staff members in Australian universities. Generally, casual employees have the most direct contact with students: they’re directly responsible for conducting tutorials, delivering guest lectures, marking assignments and exams, and providing feedback on work. Yet casual staff have limited access to basic support services, such as workplace health and safety training, professional development opportunities and mentoring. When I started work as a casual academic, I had no idea of the correct protocols for reporting sexual harassment because I didn’t receive an induction. I signed a contract, received my timetable and turned up in week one to teach.

For this reason, I also worry that current preventative measures, such as anti-bullying courses and equity awareness seminars, are ineffective. They’re not reaching the people who need them most: sessional staff and students. As one respondent to the AWHN’s survey remarked: “The answer is not more training. Our university just made all staff go through bullying training again…and it was a waste of time. Those sorts of trainings are 1. An HR tick-the-box joke, and 2. Do not actually reach the people who need them, who…will never believe they are actually doing anything inappropriate.”

Regardless of the effectiveness of anti-harassment policies and procedures, the bottom line is this: we should expect more from our universities in their work to combat sexual assault and discrimination. And we need to start with more research into the problem of contrapower harassment because this issue goes to the heart of the system: our students.

Kate Cantrell teaches creative and professional writing at Queensland University of Technology and the University of Southern Queensland. From 2015 to 2016, she was a visiting lecturer at City, University of London and an education researcher at the University of Oxford. She is also an award-winning writer and editor. This is a slightly edited version of an article that first appeared in the journal Overland.

后记

Print headline: Intimidation game