Just two months after the 9/11 attacks, Fox TV began broadcasting its series 24. The main protagonist was Jack Bauer (played by Kiefer Sutherland), an agent of the Los Angeles Counter Terrorism Unit. The first episode, which was filmed before 9/11, focused on a terrorist attempting to blow up an aeroplane and assassinate a Democratic presidential candidate. But the series’ main theme was torture: it was the only way to safeguard democracy. The Bauer character was portrayed as a morally dedicated, self-sacrificing officer of the people. Who would not torture a terrorist if it would save hundreds of innocent American lives? Torture was redemptive and ennobling. Viewers of the series were enthused by the black-and-white plots: there were clearly identified “good guys” who had a duty to ensure that the vicious plans of the “evil guys” would never materialise. Given the scale of the threat to civilised values and society, many forms of torture, including sensory deprivation and electric shocks, were necessary.

24 also brought the “ticking time bomb” defence of torture into living rooms throughout America. There are lots of versions of this defence, but most conjure up a situation in which a bomb has been placed in an unknown location. If the bomb goes off, hundreds of civilians, including children, will be killed. It is impossible to know which public space should be evacuated. The terrorist is in custody but refusing to talk. Time is running out. Should the authorities use non-lethal torture to get information that will save innocent people?

It is a compelling, hyper-realist scenario and has been one of the most pervasive arguments in favour of torture. In Donatella Di Cesare’s new book, simply called Torture and translated by David Broder, she effectively demolishes this defence. The “ticking time bomb” argument, she shows, is as unrealistic and implausible as the TV series 24. It assumes too many things, including knowledge of an attack, that the authorities have arrested the right suspect, and that torture will be effective. Why should a terrorist give correct information? Crucially, the ticking time bomb “has never played out in reality”, despite the contentions of torture advocates who continue to point to the 1995 brutalisation of Abdul Hakim Murad in the Philippines. Di Cesare argues that the “trap” in the ticking time bomb argument is that it presents an extremely compelling hypothetical scenario as though it were “empirical evidence”. In fact, “it has never actually occurred. On closer inspection, this ‘realism’ is pseudo-realism”.

The book follows other important refutations of pro-torture arguments, including Bob Brecher’s compelling Torture and the Ticking Bomb (2007), which examines similar themes. They remind us that torture is now routinely justified, not only in scruffy tabloids but in supposedly reputable legal circles. In Why Torture Works: Understanding the Threat, Responding to the Challenge (2002), the distinguished lawyer and civil libertarian Alan Dershowitz even defended the use of torture on the grounds of human rights. In his words, “we cannot reason with them [terrorists]…but we can – if we work at it – outsmart them, set traps for them, cage them, or kill them”. It is no coincidence that he employed a language more typically used to refer to the abuse of animals: the tortured are no longer fully human. He proposed allowing judges to issue “torture warrants”, which would license authorities to torture individuals (he called them “cunning beasts of prey”) suspected of concealing information about terrorist acts. The individualist, self-sacrificial torturer (such as Bauer) would be replaced by objective judges. And the needle under the fingernail would, of course, be sterilised.

Dershowitz is unfortunately not alone. Michael Ignatieff was the director of the Harvard University Carr Center for Human Rights and is a leading member (and former leader) of the Liberal Party of Canada. In The Lesser Evil: Political Ethics in an Age of Terror (2004), though, he publicly accepted torture on political realist grounds: it was the “lesser evil”. The first sentences in his book declared that “When democracies fight terrorism, they are defending the proposition that their political life should be free of violence. But defeating terror requires violence. It may also require coercion, deception, secrecy, and violation of rights.” Although Ignatieff did not want torture to become a “general practice” within democracies, he argued that “permissible duress might include forms of sleep deprivation that do not result in harm to mental or physical health, and disinformation that causes stress”.

This so-called “torture lite” (that is, exposure to heat and cold, use of drugs to confuse prisoners, forcing prisoners to stand for days and “rough treatment”) was also supported by the late Jean Bethke Elshtain, professor of social and political ethics at the University of Chicago’s Divinity School and member of President Bush’s Council on Bioethics. In a contribution to Torture: A Collection (edited by Sanford Levinson, 2006) titled “Reflection on the Problem of ‘Dirty Hands’”, she argued for an uncompromising, absolute condemnation of terrorist acts but turned into a utilitarian when she assessed torture practices committed by Americans.

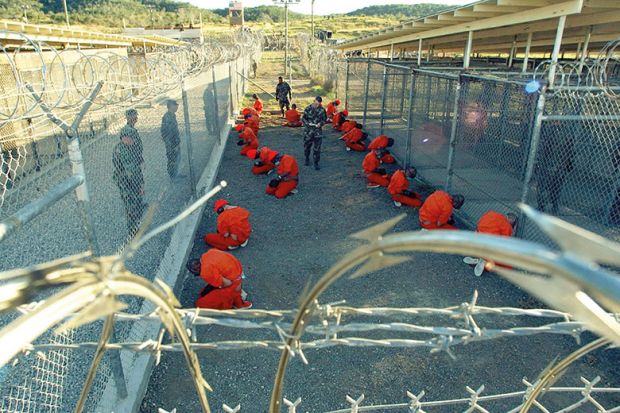

The consequences of these arguments are not “academic”. According to Amnesty International, at least 122 countries in 2016 tortured people. The legitimation of torture has practical consequences, most obviously for the men, women and children who found themselves incarcerated as suspected terrorists in Guantánamo Bay or offshore in Diego Garcia, a British territory in the Indian Ocean. So-called extraordinary rendition, whereby terrorist suspects are handed over to authorities in countries where torture is known to be used, is a common way citizens in Western democracies have been allowed to “turn a blind eye” to their government’s actions.

The startling fact is that torture and democracy are no longer seen as antitheses. In the words of Omar Rivabella in Requiem for a Woman’s Soul (1986), people “torture in the name of justice, in the name of law and order, in the name of the country, and some go so far as pretending they torture in the name of God”. There has been what Di Cesare calls the “democratization of torture”.

People actually get accustomed to barbarian ways. Simone de Beauvoir – an ardent opponent of torture during the French-Algerian War – stated that “in 1957, the burns in the face, on the sexual organs, the nails torn out, the impalements, the shrieks, the convulsions, outraged me”. But, by the “sinister month of December 1961, like many of my fellow men, I suppose, I suffer from a kind of tetanus of the imagination…One gets used to it”.

What can be done? “How can we fight against torture”, Di Cesare asks, “if the criminal is the state itself? Or, indeed, if the state denies it is carrying out such a practice?” Here, she calls for greater vigilance. Citizens need to hold their governments to account for their evil actions – even when these actions take place in other parts of the globe. The only thing that will defeat torture is “the barrier of disobedience and words that break the silence”.

Joanna Bourke is professor of history at Birkbeck, University of London, and the author of Wounding the World: How Military Violence and War Games Invade Our Lives (2016).

Torture

By Donatella Di Cesare; translated by David Broder

Polity, 168pp, £50.00 and £16.99

ISBN 9781509524365 and 4372

21 September 2018

The author

Donatella Di Cesare, professor of theoretical philosophy at Sapienza University in Rome, was born in that city, spent her early years in Sicily and then returned to Rome at the age of eight. She studied initially at Sapienza University and then spent many years at the University of Tübingen and Heidelberg University.

This experience had a deep impact on her, she recalled, because she “saw Germany as the cradle of philosophy – the land of Kant and Hegel. But at the same time it was a country where the Third Reich could establish itself, and it struck me that this recent past was hardly discussed. I wondered and still wonder what the connection is between that great culture and the abyss of Auschwitz.”

“The issue of violence” has remained at the heart of Di Cesare’s thinking. “What strikes me about torture in particular is that it is a practice tacitly allowed within democratic states. I was appalled at Guantánamo, a symbolic flesh wound in the Western idea of democracy. The brutal crackdown on protesters in Genoa during the 2001 G8 summit was also terrible. Finally, I was shocked by the case of Giulio Regeni [the Italian Cambridge graduate student who was killed in Egypt], which I recount in the book,” she said.

Asked about three core lessons that she hoped policymakers would take away from her book, Di Cesare claimed that “As soon as the State touches the body of a citizen, it becomes illegitimate – those who govern should never forget this.” Torture had “the repulsive taste of a regression into the state of nature, where the rule of law is completely obliterated”. It was also “a unique form of repeated and systematic violence, and as such exhibits the traits of a sophisticated cruelty. This must not be forgotten by individuals or communities.”

Matthew Reisz

后记

Print headline: Brutality ‘in the name of justice’

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?